|

THE

GREAT PACIFIC

GARBAGE

PATCH

- UPDATE 2018

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

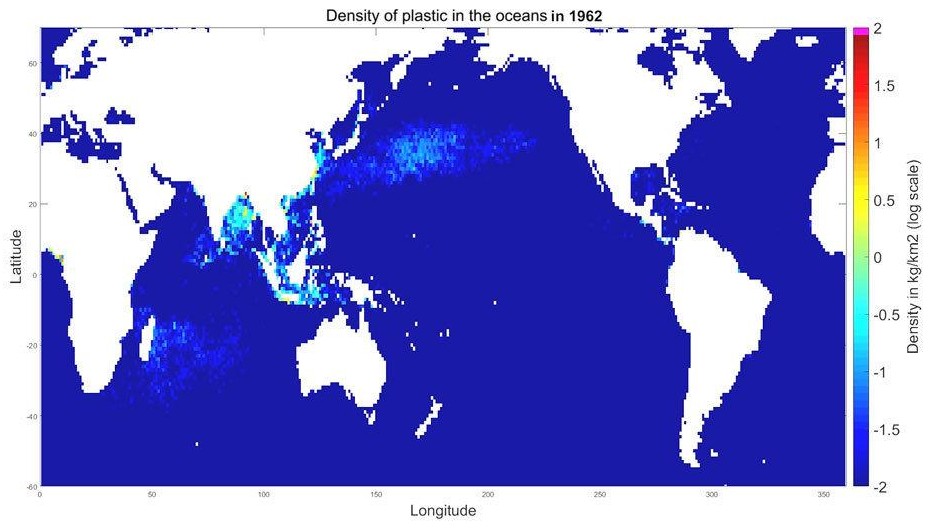

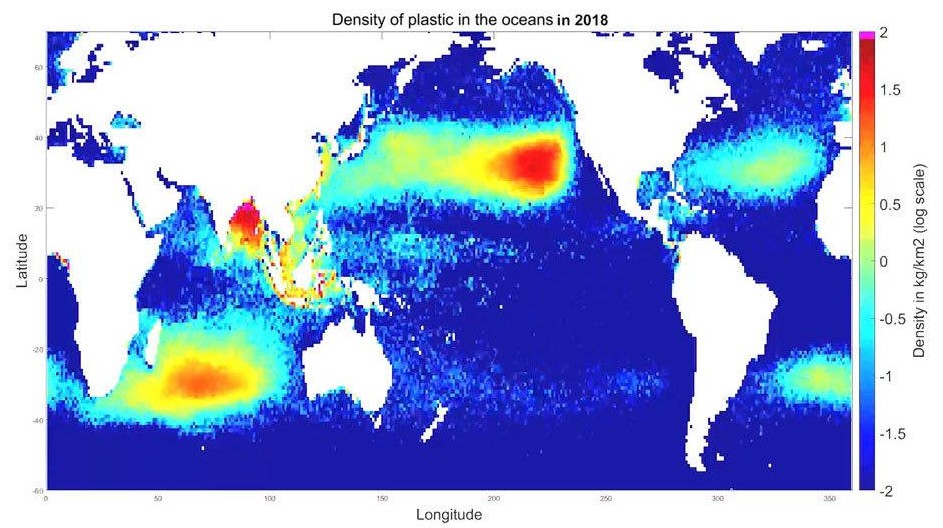

GETTING

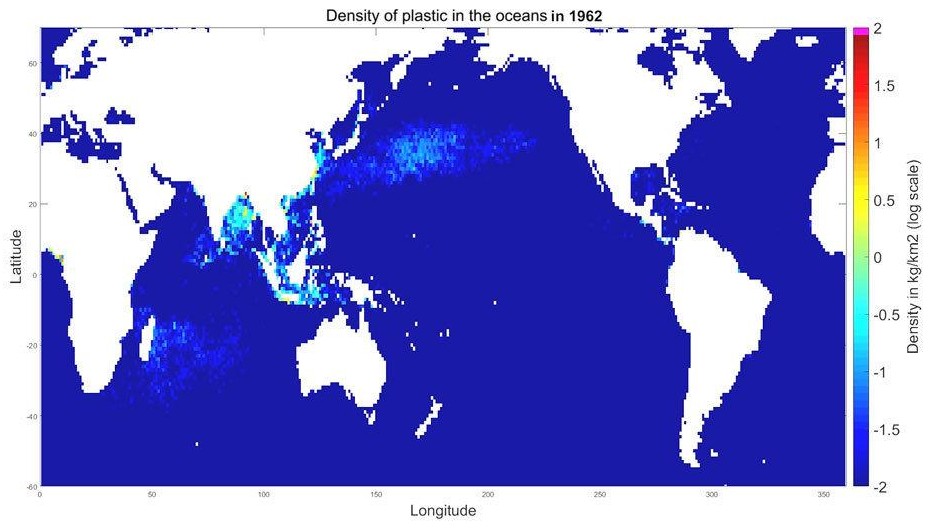

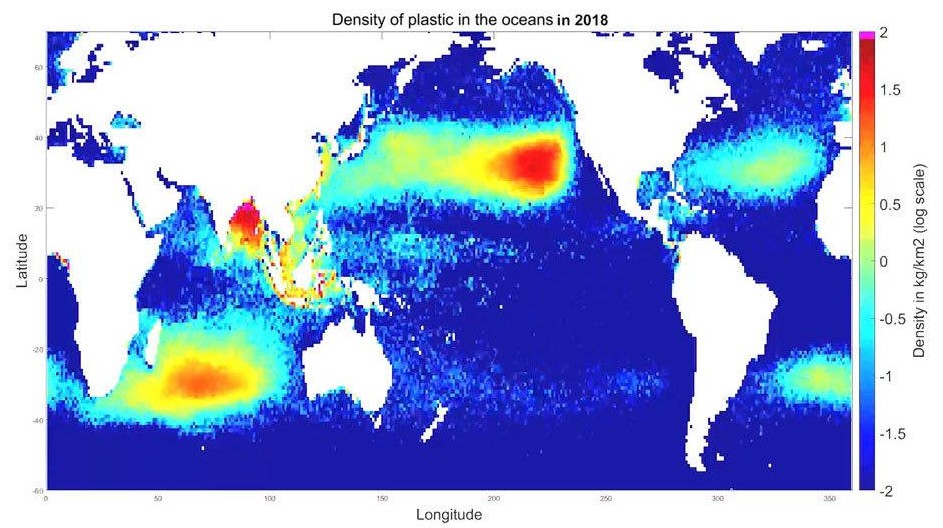

BIGGER - It's out of

control. Compare the plots below from 1962 against that for

2018 and it's obvious that if funding is not made available

for machines like SeaVax, we will soon have more plastic in

the oceans than fish, as predicted by studies last year.

When you think of the Pacific Ocean, you think of paradise,

tropical islands and clear aquamarine waters. You do not think

of carcinogenic

waste and subsurface rubbish, but that is the awful truth. The

life of many islanders is under attack with rising sea levels

and climate change and death all around them, whether it is a turtle

with a plastic straw in its nose, a whale with a belly full of

plastic

or a flock of seabirds dying from hunger because they have

eaten so many plastic

bottle caps.

The

UN's Agenda 2030 kicks off with a 5 year period from 2018 to

2023 to move the blue growth agenda into another gear with

specific sustainability

development goals (SDGs) of which 14 concerns our oceans

and seas. How that may or may not translate into action or

funding for projects like SeaVax remains to be seen. One would

hope that

SWALLOWED - The

contents of the stomach of a sea turtle (according to the Ocean Cleanup

Foundation) which is funding research into plastic debris found in the Pacific.

NEW YORK TIMES MARCH 22 2018 - THE

GREAT PACIFIC OCEAN PATCH IS BALLOONING

In the Pacific Ocean between California and Hawaii, hundreds of miles from any major city, plastic bottles, children’s toys, broken electronics, abandoned fishing nets and millions more fragments of debris are floating in the

water — at least 87,000 tons’ worth, researchers said Thursday.

In recent years, this notorious mess has become known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a swirling oceanic graveyard where everyday objects get deposited by the currents. The plastics eventually disintegrate into tiny particles that often get eaten by fish and may ultimately enter our food chain.

A study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports quantified the full extent of the so-called garbage patch: It is four to 16 times bigger than previously thought, occupying an area roughly four times the size of California and comprising an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of rubbish. While the patch was once thought to be more akin to a soup of nearly invisible microplastics, scientists now think most of the trash consists of larger pieces. And, they say, it is growing “exponentially.”

“It’s just quite alarming, because you are so far from the mainland,” said Laurent Lebreton, the lead author of the study and an oceanographer with the

Ocean Cleanup

Foundation, a nonprofit that is developing systems to remove ocean trash and which funded the study. “There’s no one around and you still see those common objects, like crates and bottles.”

JUST

ONE WORD: PLASTICS

In the late summer of 2015, Mr. Lebreton and his colleagues measured the amount of plastic debris in the patch by trawling it with nets and flying overhead to take aerial photographs. Though they also found glass, rubber and wood, 99.9 percent of what the researchers pulled out of the ocean was plastic.

They also recovered a startling number of abandoned plastic fishing nets, Mr. Lebreton said. These “ghost nets” made up almost half of the total weight of the debris. (One explanation is the patch’s proximity to fishing grounds; another is that fishing material is designed to be resilient at sea and stays intact longer than other objects.)

“We found a few unexpected objects,” Mr. Lebreton said. “Among them were plastic toys, which I found really sad, as some of them may have come from the tsunami in Japan,” he added, referring to the 2011 disaster that sent millions of tons of debris into the ocean.

The researchers also fished out a ’90s-era Game Boy cover, construction-site helmets and a toilet seat, as well as a number of objects with Japanese and Chinese inscriptions. Other objects, Mr. Lebreton said, had “little bite marks from fish.”

Some sea turtles caught near the patch were eating so much plastic that it made up around three-quarters of their diet, according to the foundation.

THE GARBAGE PATCH IS NOT EXACTLY A "PATCH”

After its discovery in the late ’90s, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch took on an image in the popular imagination akin to an island or even a seventh continent made of trash. That myth was debunked, and the patch became understood as more like a region that looked like the rest of the ocean to the naked eye, but was polluted with tiny microplastics.

However the new study says that the microplastics, while still a problem, account for just 8 percent of the mass of the patch. Until now, most of the sampling used an ocean trawl designed to pick up small particles, and therefore, Mr. Lebreton said, underestimated the number of larger pieces of debris floating in the sea, like bottles, buoys and fishing nets.

“Most of the mass is actually large debris, ready to decompose into microplastic,” Mr. Lebreton said.

Still, “it’s not an island,” Mr. Lebreton said. “It’s very scattered.” (A visual model, however, shows how the debris is condensed in one area in the

ocean.)

"I think the name ‘patch’ is a little bit confusing,” said Nancy Wallace, the director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program, who was not involved in the study. Describing it that way, she said, gave the wrong impression that it “would be easy to go pick it up.”

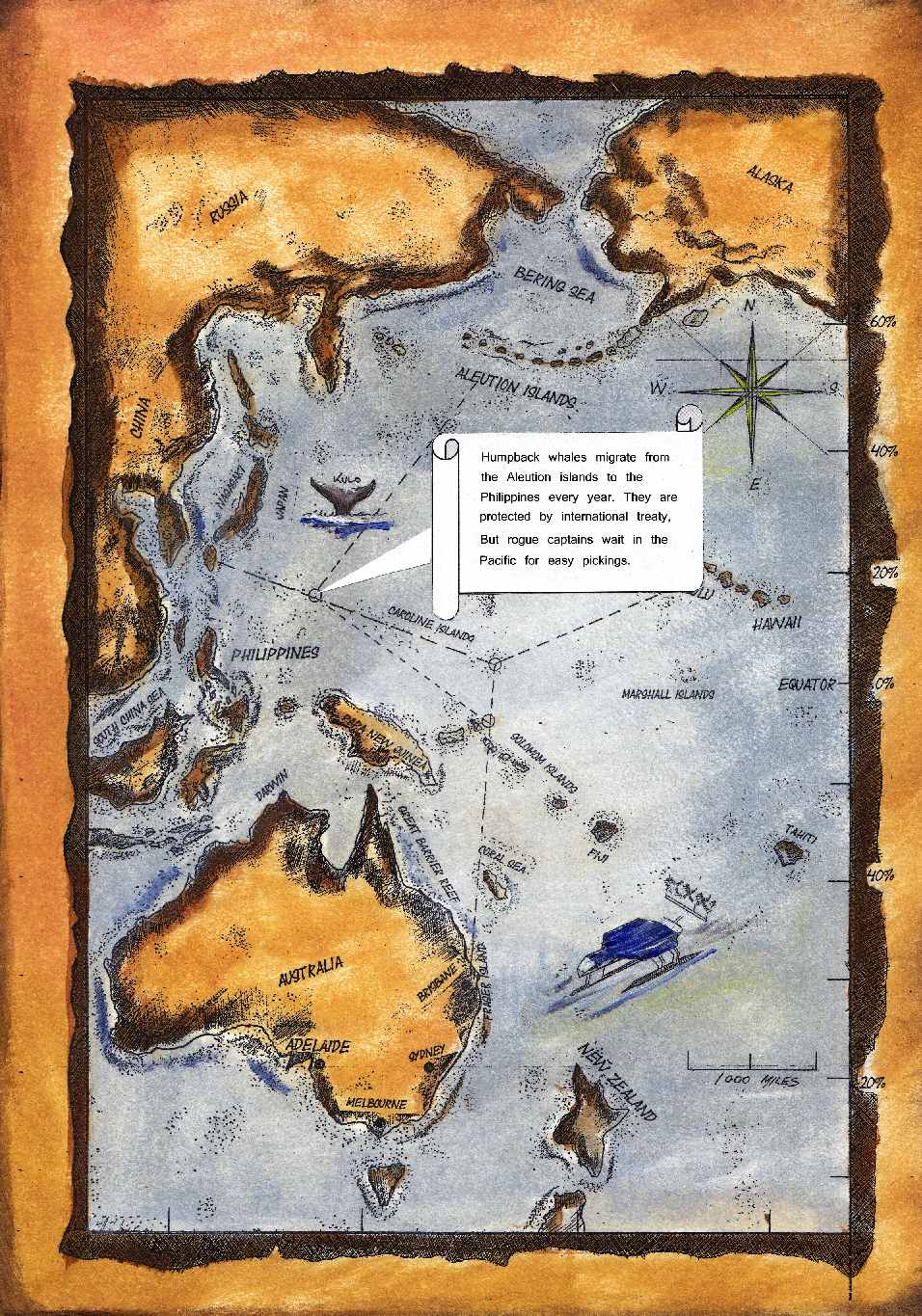

The

map above shows you where a humpback whale's fight for life

begins and ends, with plastic waste featuring high on the

agenda. Copyright © Jameson Hunter 2006 and 2018. The right of

Jameson Hunter to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. In this work of fiction, the characters, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or they are used entirely fictitiously.

Blueplanet Universal Productions & Electrick Publications, London, England. ISBN: 0-953-7824-01

THERE MAY STILL BE TIME TO ACT

The worry is that, within a few decades, the larger pieces of debris could break up into microplastics, which are much harder to remove from the ocean. “It’s like a ticking time bomb,” said Joost Dubois, a spokesman for the Ocean Cleanup Foundation.

The foundation says it would be almost impossible to remove the plastic already in the patch by traditional methods, like nets attached to boats. Instead, the group has developed a mechanical system that floats through the water and concentrates the plastics into denser areas that can then be collected by boats and taken back to shore to be recycled.

The foundation plans to launch the first such system this summer from Alameda, Calif.

By Livia Albeck-Ripka

- a reporting fellow at The New York Times. @livia_ar

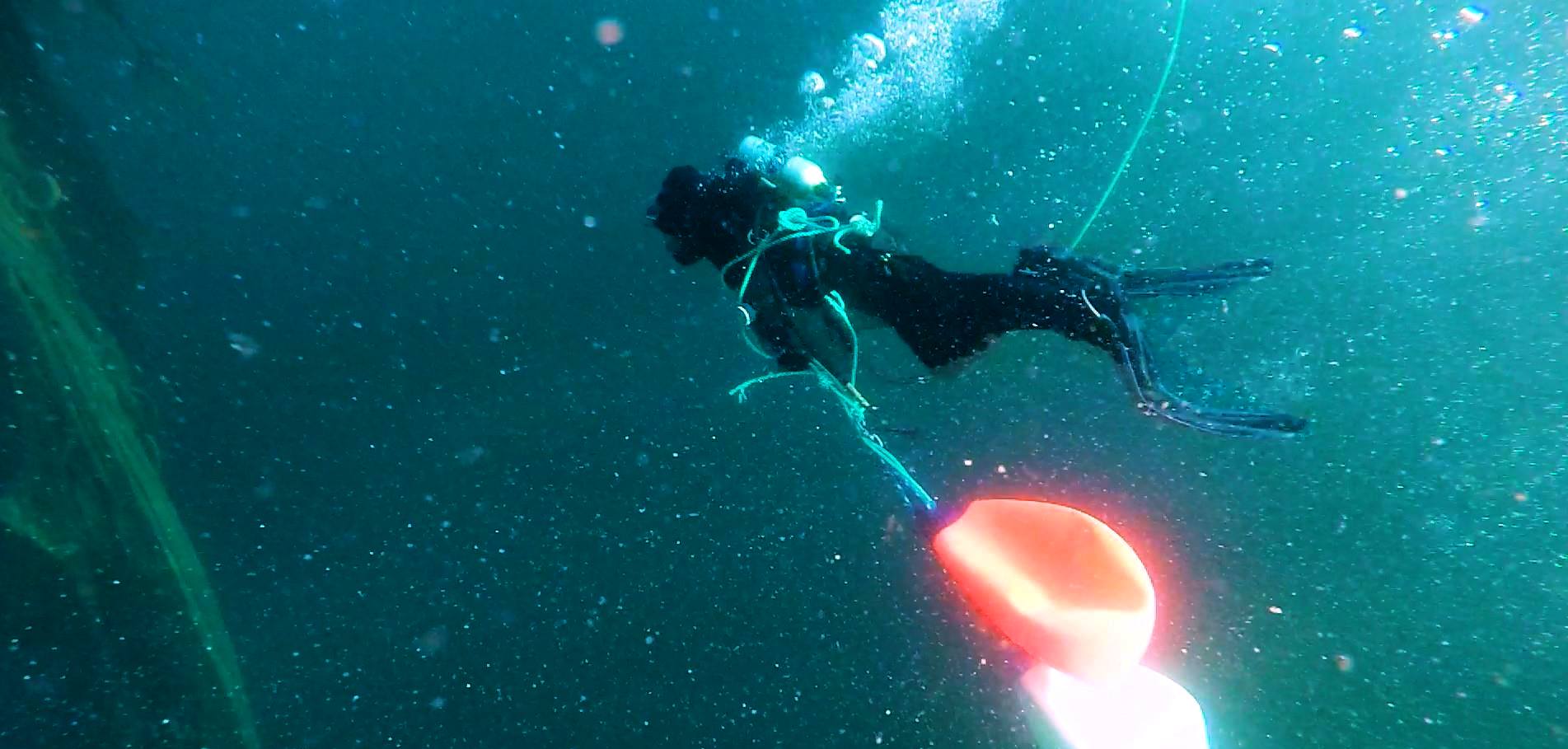

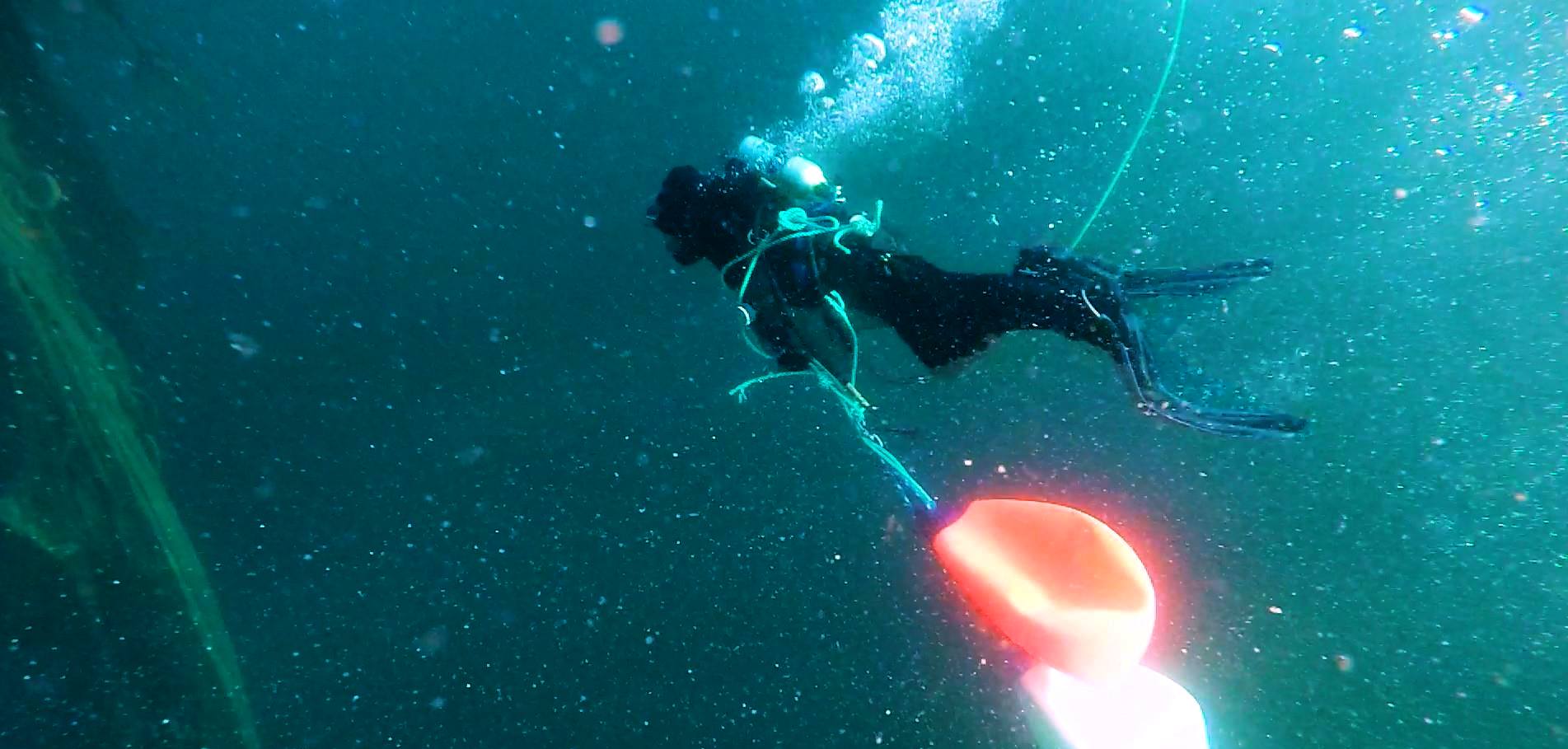

GHOST

NETS - Hundreds

of tons of ghost fishing nets litter the oceans to trap unwary

marine life.

2018

STUDY EXTRACT

Ocean plastic can persist in sea surface waters, eventually accumulating in remote areas of the world’s oceans. Here we characterise and quantify a major ocean plastic accumulation zone formed in subtropical waters between California and Hawaii: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). Our model, calibrated with data from multi-vessel and aircraft surveys, predicted at least 79

thousand tonnes of ocean plastic are floating inside an area of 1.6 million km2; a figure four to sixteen times higher than previously reported. We explain this difference through the use of more robust methods to quantify larger debris. Over three-quarters of the GPGP mass was carried by debris larger than 5 cm and at least 46% was comprised of fishing nets. Microplastics accounted for 8% of the total mass but 94% of the estimated 1.8

trillion pieces floating in the area. Plastic collected during our study has specific characteristics such as small surface-to-volume ratio, indicating that only certain types of debris have the capacity to persist and accumulate at the surface of the GPGP. Finally, our results suggest that ocean plastic pollution within the GPGP is increasing exponentially and at a faster rate than in surrounding waters.

STUDY

DETAILS

Global annual plastic consumption has now reached over 320 million tonnes with more plastic produced in the last decade than ever before1. A significant amount of the produced material serves an ephemeral purpose and is rapidly converted into waste. A small portion may be recycled or incinerated while the majority will either be discarded into landfill or littered into natural environments, including the world’s oceans2. While the introduction of synthetic fibres in fishing and aquaculture gear represented an important technological advance specifically for its persistence in the marine environment, accidental and deliberate gear losses became a major source of ocean plastic

pollution. Lost or discarded fishing nets known as ghostnets are of particular concern as they yield direct negative impacts on the economy and marine habitats worldwide.

Around 60% of the plastic produced is less dense than

seawater. When introduced into the marine environment, buoyant plastic can be transported by surface currents and

winds, recaptured by coastlines, degraded into smaller pieces by the action of sun, temperature variations, waves and marine

life, or lose buoyancy and sink. A portion of these buoyant plastics however, is transported offshore and enters oceanic

gyres. A considerable accumulation zone for buoyant plastic was identified in the eastern part of the North Pacific Subtropical

Gyre. This area has been described as ‘a gyre within a

gyre’ and commonly referred to as the ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’. The relatively high concentrations of ocean plastic occurring in this

region are mostly attributed to a connection to substantial ocean plastic sources in

Asia through the Kuroshio Extension (KE) current system as well as intensified

fishing activity in the Pacific

Ocean.

Most available data on quantities and characteristics of buoyant ocean plastic are derived from samples collected with small sea surface trawls initially developed to collect neustonic

plankton. Due to their small aperture (0.5–1 m width, 0.15–1 m depth) and limited surface area covered, they could underestimate loads of rarer and larger plastic objects such as bottles, buoys and fishing nets. In an attempt to overcome this misrepresentation, a research

team combined net tow data with information from vessel-based visual sighting surveys. They found that while small, millimetre-sized pieces (<4.75 mm) count in trillions at global scale, they only represent a small mass portion (13%) of the total available buoyant material. Nevertheless, vessel-based sightings data yielded high uncertainties due to differences in survey protocols across research groups and difficulties in estimating the mass of sighted objects. Historical datasets on buoyant ocean plastic are also sparse in space and

time. To circumvent such limitations, recent studies have coupled

datasets with dispersal models to predict ocean plastic pollution levels worldwide. Outputs from ocean plastic transport model are generally integrated over several years and calibrated against datasets collected during different seasons, years and decades. However, such method may misrepresent ocean plastic transportation and accumulation as these processes are closely associated with seasonal and inter-annual

variability.

In this study, we characterized and quantified buoyant ocean plastics inside the GPGP. Between July and September 2015, we conducted a multi-vessel expedition to collect surface trawl samples within and around the GPGP region and obtain a representative distribution of buoyant

plastic concentrations in this region. In October 2016, we conducted an aerial survey to obtain geo-referenced imagery that sampled greater sea surface area and improved estimations for debris larger than 0.5 m. Our final dataset, containing measured concentrations for ocean plastic of various sizes and types, was used to calibrate a multi-source and multi-forcing ocean plastic transport model. We calibrated our numerical model using monthly averages of predicted concentrations that reflected seasonal and inter-annual changes of the GPGP position. As such, this study is a first attempt at introducing a time-coherent dynamic model of floating debris accumulation in the GPGP. This allowed us to compare our findings with historical observations (1970s to present) and assess the long-term evolution of ocean plastic concentrations within and around the GPGP.

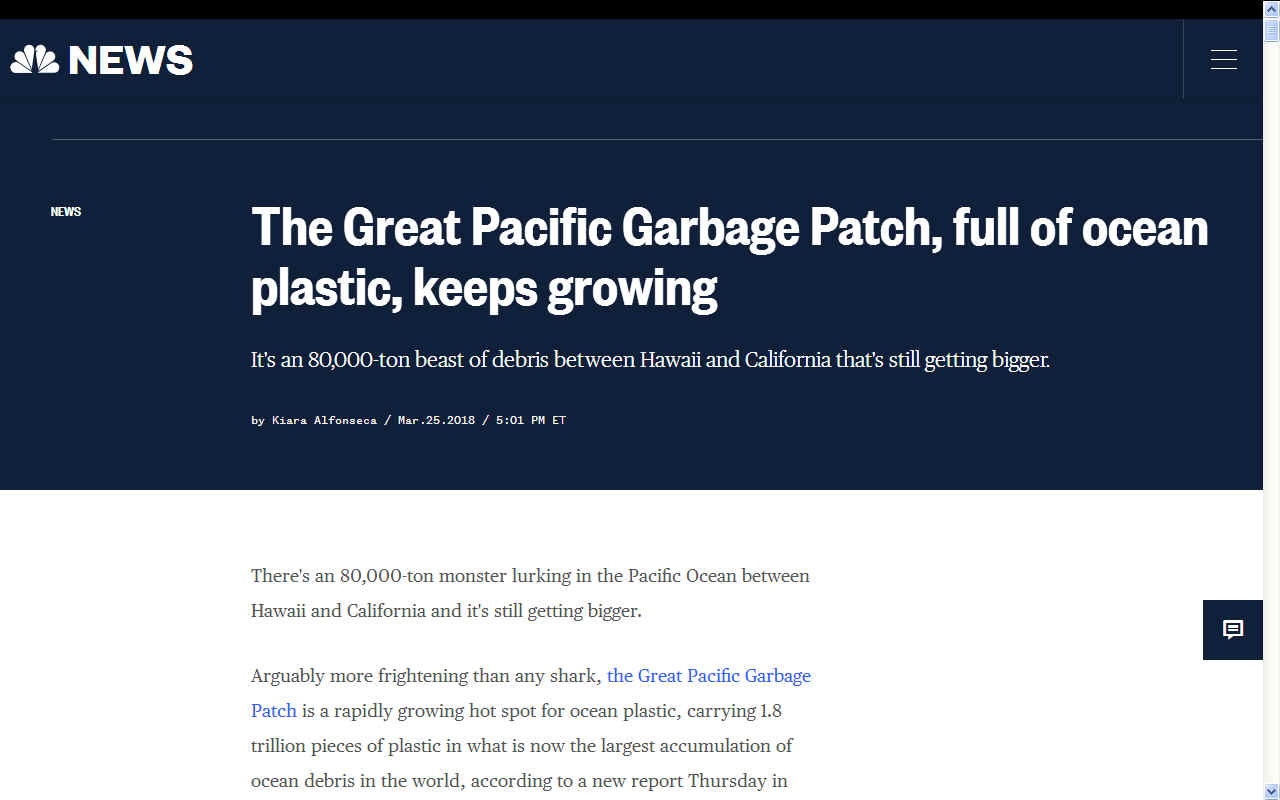

NBC

NEWS 25 MARCH 2018 - GARBAGE PATCH FULL OF PLASTIC KEEPS

GROWING

There's an 80,000-ton monster lurking in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and California and it's still getting bigger.

Arguably more frightening than any shark, the Great

Pacific Garbage Patch is a rapidly growing hot spot for ocean plastic, carrying 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic in what is now the largest accumulation of ocean debris in the world, according to a new report Thursday in Scientific Reports.

The patch is now two times larger than the size of Texas, with bits of plastic and debris spread over more than 600,000 square miles of water, according to the three-year mapping effort from eight different organizations.

Meanwhile, the annual consumption of plastic is on the rise around the world and currently totals more than 320 million tons, according to the report.

"To solve a problem, we need to understand it first," said Boyan

Slat, CEO and founder of The Ocean Cleanup, the non-profit organization that led the research initiative. "There's a good part to it and a bad part to it. The bad part is that there is more [trash and plastic] than what we thought. But the good part is that most of the plastic is still large object. Just 8 percent of the plastic is

microplastic. It's not too late to do something about it."

Nick Mallos, however, isn't surprised by the numbers in the report. Instead, as the director of the Ocean Conservancy's Trash Free Seas Program, he sees this as an opportunity for action.

The most effective way to stop the flow of plastic into waterways, he said, is to monitor our consumption and disposal of plastic and debris.

"We have a role to think about how we are consuming and how we are living our daily lives," Mallos said. "At the end of the day, ocean plastic isn't an ocean problem, but a people problem. [The Great Pacific Garbage Patch] can seem so far away and foreign to you, but the ocean is always downstream. We all have the power to make individual, small changes."

The inflow of plastic is more than the outflow, meaning groups like The Ocean Cleanup and other private or non-profit organizations are continuously looking for ways to stop the course of discarded plastic in its tracks.

The Ocean Cleanup will use this research to improve its methods of cleanup, including its technology to capture, concentrate, and ship the materials from the patch back to land. The technology will be tested in April, according to a spokesperson for the group.

Approximately half of the debris found in the patch is comprised of fishing gear, an alarming statistic for those who study marine life and ocean debris. Mallos describes the gear as "meant to kill," and when they are lost and discarded into oceans, they damage ecosystems and become deadly to marine life.

"This is also consistent with what [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration] has found and is concerning because of the impacts this gear can have on a range of marine animals," wrote Nancy Wallace, the director of the NOAA's Marine Debris Program.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch isn't the only accumulation of debris in the world's oceans, water currents and wind also collect debris is four other areas known as gyres. Those are located in the South Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the North and South Atlantic Ocean.

"Since the marine debris issue is caused by humans, we can make great strides in turning this problem around," wrote Wallace. "We need to focus on generating less waste and stopping the flow of debris into our waterways and ocean. This will take significant effort, but awareness around this issue is growing and people are willing to make changes to make an impact".

SORTING - As part of the study, researchers sorted plastic by size to begin to understand how the material breaks down at sea.

NO

NET FISHING BOATS

- It is possible to fish using a system that does not rely

totally on plastic nets. Where around 45% of the Pacific

Garbage Patch is made up of ghost nets. Any move away from

dependence on plastic that could end up killing marine life

should be investigated.

Vertical

Axis Wind Turbines are the subject of investigation, with a

new design that could bridge the gap between horizontal axis

turbines in terms of power to weight ratio. Any advantage in

terms of wind conversion is amplified by the ability to raise

the blades higher into the air stream to escape the boundary

layer at deck level. The front turbine is raised, the rear is

lowered. They can also be furled.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-22939-w#Sec15

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2017/09/28/plastic-junk-brought-invasive-species-to-u-s-after-japans-2011-tsunami/

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/the_next_20/2016/09/the_great_pacific_garbage_patch_was_the_myth_we_needed_to_save_our_oceans.html

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/great-pacific-garbage-patch-full-ocean-plastic-keeps-growing-n859276

FISHING

NETS - MICROBEADS - MICRO

PLASTICS - OCEAN GYRES - OCEAN WASTE - PLASTIC

- POPS

GANGES

- NILE

OCEAN

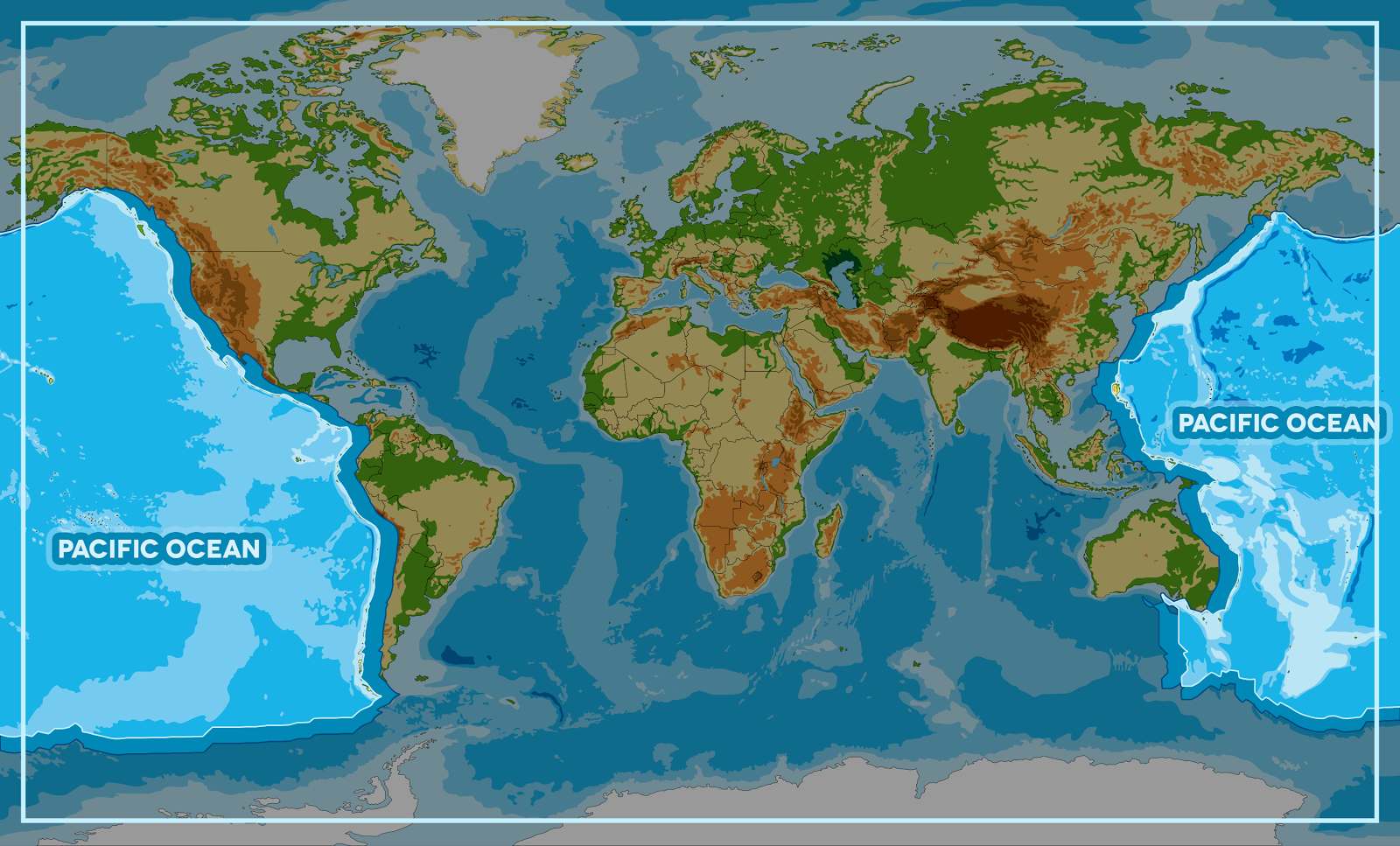

AWARENESS CAMPAIGN - As

part of the Cleaner Ocean Foundation's ocean

literacy campaign, we are developing a game that can be

played on mobile devices like the iphone or android smart

phones. In this game children learn a little about geography

as they select one of five ocean areas to rid of marine

litter. The screen above shows that the player has selected

the Pacific Ocean to tackle. Copyright Map © January 29 2018

all rights reserved COF

Ltd. The name SeaVax

is a registered ® trademark.

AEGEAN

- ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- AMBRACIAN

GULF

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC

- BALTIC

- BAY

BENGAL - BAY

BISCAY - BERING

- BLACK

- CARIBBEAN

- CASPIAN

- CORAL

- EAST

CHINA SEA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC

- GUANABARA

- GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN

-

IRC - IONIAN - IRISH

- MEDITERRANEAN

- NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN

GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - RED

- SARGASSO

- SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN - TYRRHENIAN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

- WOC

- WWF

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2025. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital. The names Amphimax™

and SeaVax™

are trademarks.

|