|

BOARD OF LONGITUDE

ABOUT - CLIMATE CHANGE A-Z - CONTACTS - CROWDFUNDING - DONATE - FOUNDATION - HOME - OCEAN PLASTIC A-Z Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

1714

- 1828 - 114 YEARS OF PROCRASTINATION - The thirst to expand the known world drove a centuries-long quest to find a better method of navigation.

Navigators and scientists had been working on the problem of not knowing a ship's longitude. The establishment of the Board of Longitude was motivated by this problem and by the 1707 grounding of four ships of Vice-Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell's fleet off the Isles of Scilly, resulting in heavy loss of life.

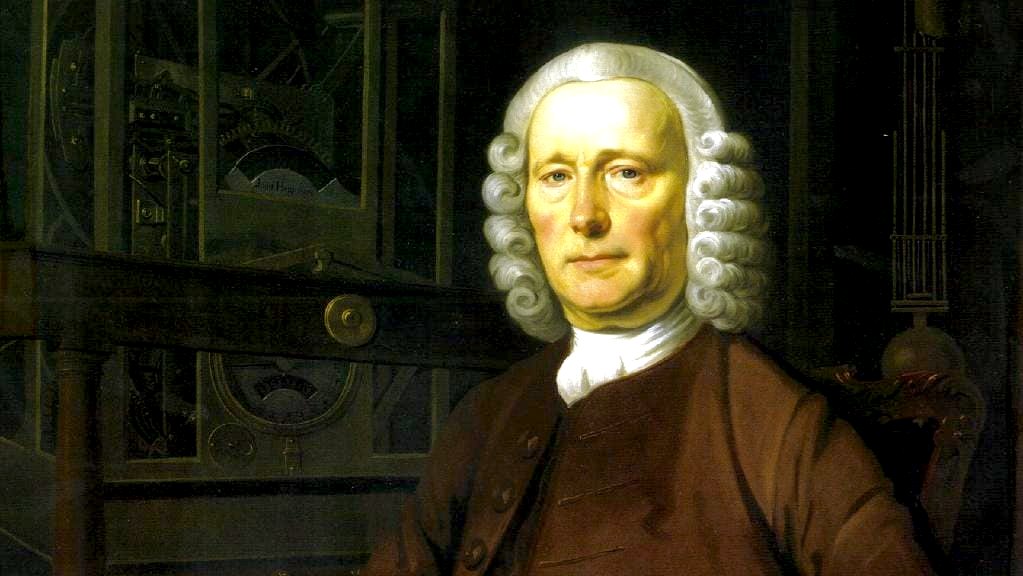

Established by Queen Anne the Longitude Act 1714 named 24 Commissioners of Longitude, key figures from politics, the Navy, astronomy and mathematics. However, the Board did not meet until at least 1737 when interest grew in John Harrison's marine timekeeper.

From our knowledge of Smart Awards, and other Dti or Enterprise grants and prizes offered by various Government bodies as incentives to encourage inventors to solve the problems they need solving, such bodies invariably react to changing circumstances at a snails pace and typically award monies to more established concerns with vested interests, but not to those with solutions who are outside any established ring of favoured developers, and never to those without a good financial track record who are most in need of a boost, where they may be seen as more of a gamble.

That explains why in the main why we never see any radical changes, except with consumer electronics, where speed advances the breed year on year for performance hungry consumers.

Boards of so-called experts are therefore self-defeating to some extent. One such institution has gone down in history for it's inability to see the wood for the trees. Even when they held the solution in their hands they refused to recognize it. Experts on boards appear not to understand urgency, such as we are facing today with climate change.

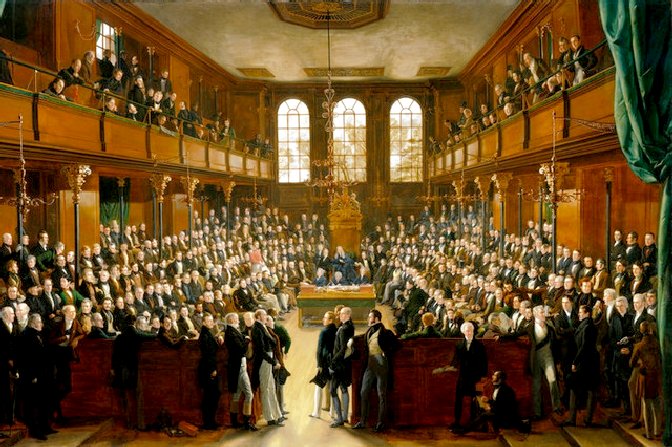

PARLIAMENT DEBATE - For centuries sailors used the stars, land sightings, currents, intuition and observation to establish their position at sea. They were neither a precise nor reliable means of navigation, which made travel by sea diabolically risky.

GERARDUS MERCATOR

GAVE US LINE OF LATITUDE & LONGITUDE

If the sun reached noon earlier than it did at Greenwich, then the ship was west of that point, and if later, then it was east. Each hour equated to 15 degrees of longitude. That was the genius of Mercator's lines.

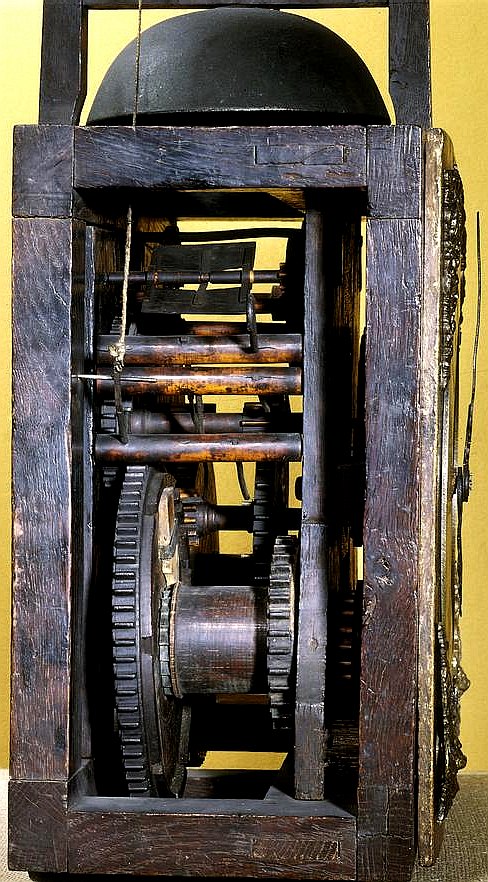

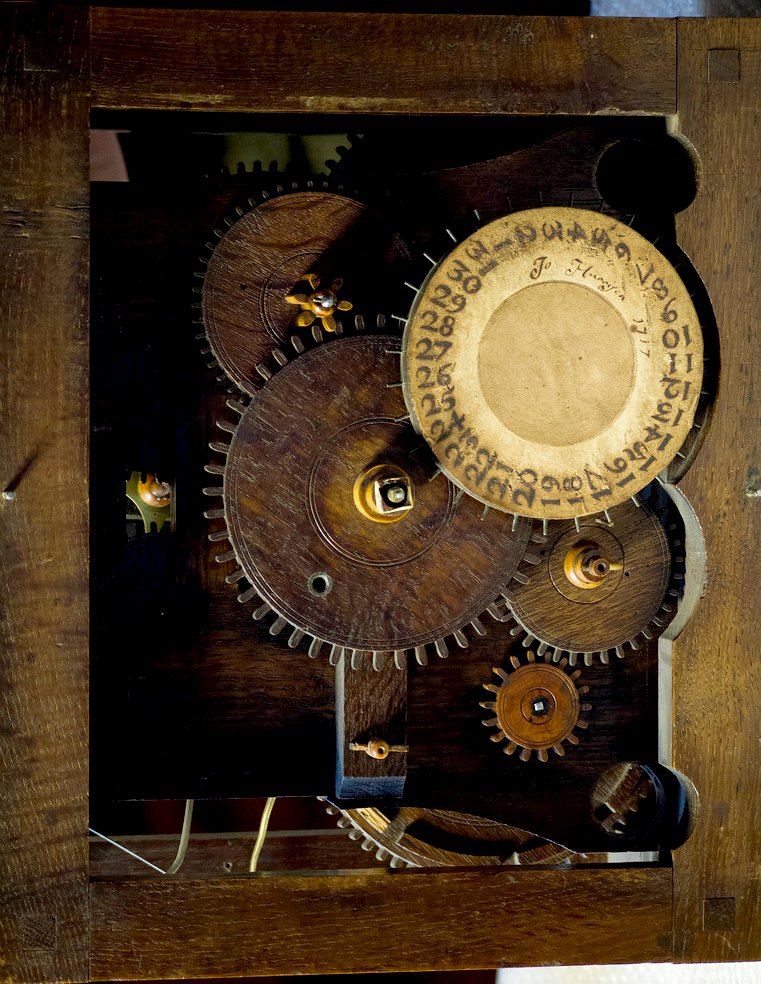

WOOD IS GOOD - 1715 - [Left] Original eight day clock by John Harrison, wheel work mostly of wood. This clock was made by the chronometer pioneer at the age of 22, before he began his celebrated project to build a chronometer accurate enough to find a ship's longitude at sea. Although the design of the clock is conventional it is made almost entirely of wood. It is thought wood was used to reduce the need for lubrication, but also because Harrison was a carpenter by trade. The clock movement was weight-driven and would have been mounted in a long case with a pendulum. This timepiece is part of the Science Museum collection.

ROYAL NAVY 1707 GROUNDING

In 1707 four ships of

the Royal Navy under the command of Vice Admiral Cloudesley Shovell ran aground off the Scilly Isles while returning from the

Mediterranean.

And so the Board of Longitude was born with a mission to find new ways to fix an east-west position at sea, a notoriously harder problem than finding latitude which can be determined from the position of the Sun.

The Board offered some extravagant prizes up to £20,000 - some $5 million today - for anyone who could locate a position with an accuracy of 30 nautical miles (56 km) accuracy.

It thought of such a large prize gave rise to some crazy ideas. One impractical scheme was to position barges across the Atlantic, from which the crew would let off fireworks so sailors knew their position. If you think about it, satellites in space do something similar.

But the Board’s experts eventually settled on one basic concept which is still in use today - to contrast the time on the ship with the time at a fixed reference point known as Greenwich Mean Time or GMT. So if the time in the home port is 1 pm when the sun in your current location is at its midday zenith, then you know you are 15 degrees of longitude west of the port.

THE LONGITUDE ACT 1717

The Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea, or more popularly Board of Longitude, was a British government body formed in 1714 by an act of parliament to administer a scheme of prizes intended to encourage innovators to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Most early navigators relied on dead reckoning, making estimates of distance travelled from a fixed point by measuring the speed of the ship. This was done by dropping over the side a rope tied to a log, with knots tied in the rope at set lengths. The number of knots that passed over the gunwale (the rail) of the ship over a set time (measured by an hourglass) would give a rough idea of the speed of the ship. These would be recorded to give some sense of how far the ship had travelled, giving us the maritime terms “ship’s log” and “knots”.

HOLD ON, HE MAY HAVE A POINT - For many decades a sufficiently accurate chronometer was prohibitively expensive. The lunar distance method was used by mariners either in conjunction with or instead of the marine chronometer. However, with the expectation that accurate clocks would eventually become commonplace, John Harrison showed that his method was the way of the future. To its discredit, the Board never awarded the prize to Harrison, nor anyone else. It took a petition to the King to force payments.

SCALE OF REWARDS

The

Board

of Longitude administered prizes for those who could demonstrate a working device or method. The main longitude prizes were:

- £15,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 40 nautical miles (74 km; 46 mi) (£1,900,000 as of 2016)

-

£20,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) (£2,600,000 as of 2016).

An award of £3,000 went to the widow of Tobias Mayer, whose lunar tables were the basis of the lunar data in the early decades of The Nautical Almanac. £300 went to Leonhard Euler for his (assumed) contribution to the work of Mayer, £50 each to Richard Dunthorne and Israel Lyons for contributing methods to shorten the calculations connected with lunar distances, and various awards made to the designers of improvements in marine chronometers.

H4 and H5 - This magnificent clock is the one that secured the prize money for John Harrison.

Born in 1693 in Yorkshire, Harrison had long been obsessed with making an accurate timepiece. He realised a clock to determine longitude would need to be able to function aboard a rocking ship, in different temperatures and climates. Harrison took five years to produce his first timepiece specifically for the longitude reward in 1730. H1 as it was known, contained mechanisms to compensate for temperature and ship’s motion. It performed well enough for Harrison to be granted £500 from the Longitude Board to develop it.

John Harrison perfected his device with H4, a watch with a hand crank that was only 13cm in diameter and presented to the board in 1765. But despite positive tests Harrison struggled to get his reward. It was not until 1772 that he was given £10,000 for his device and a further £8000 in 1773 after a meeting with the king, but Harrison was never officially awarded the prize. Only after King George III intervened did the first tranche of the £20,000 prize for solving the problem come his way. By this time Harrison was 79-years-old.

Even though many tried their hand at winning the main prize, for decades none was able to come up with a practical solution to the problem. The Board recognised that any serious attempt would be based on the recognition that the earth rotates through 15° of longitude every hour.

The comparison of local time between a reference place (e.g., Greenwich) and the local time of the place in question would determine the longitude of that place. Since local apparent time could be determined with some ease, the problem revolved around finding a means of determining (or in the case of chronometers, keeping) the time of the reference place when one is far away from it.

John Harrison showed that his method was the way of the future. However the board, to its discredit, never awarded the prize to Harrison, nor anyone else. It took the intervention of King George III.

The tragedy is that the board of sneaks continually wrangled the rules so that poor old John, who basically saved the lives of countless seafarers of the future, never actually got more than about half the cash hr should have received until he was to old to benefit from it.

With the significant problems considered as solved, the Board of Longitude was abolished by Act of Parliament in 1828 and replaced by a Resident Committee for Scientific Advice for the Admiralty consisting of three scientific advisors: Thomas Young, Michael Faraday and Edward Sabine.

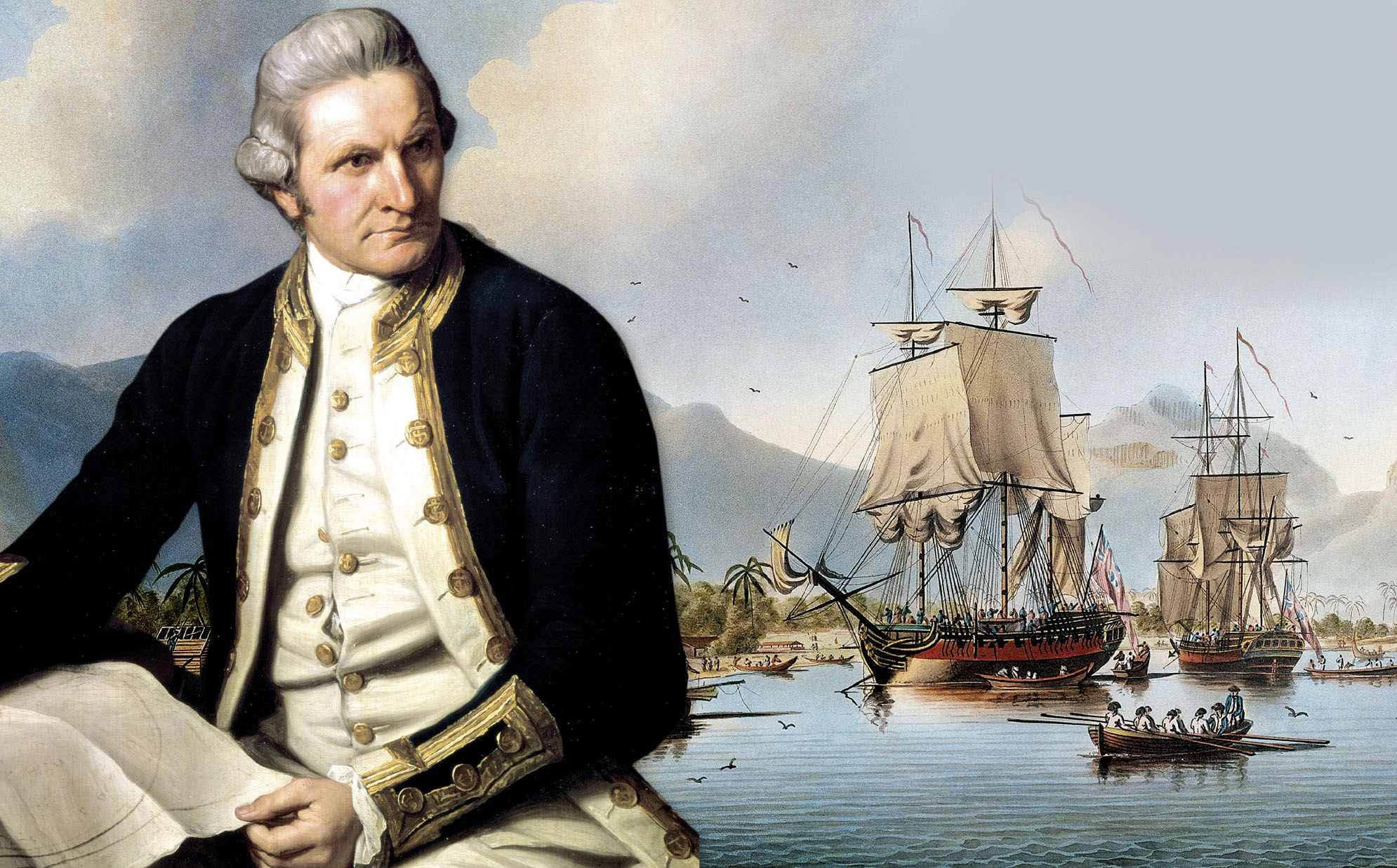

CAPTAIN

JAMES COOK

LINKS & REFERENCE

https://www.

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. Copyright © Cleaner Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774) 2019. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom. COFL is a charity without share capital. The names Amphimax™ RiverVax™ and SeaVax™ are trademarks.

|