|

DDT

ABOUT - CONTACTS - FOUNDATION - HOME - A-Z INDEX

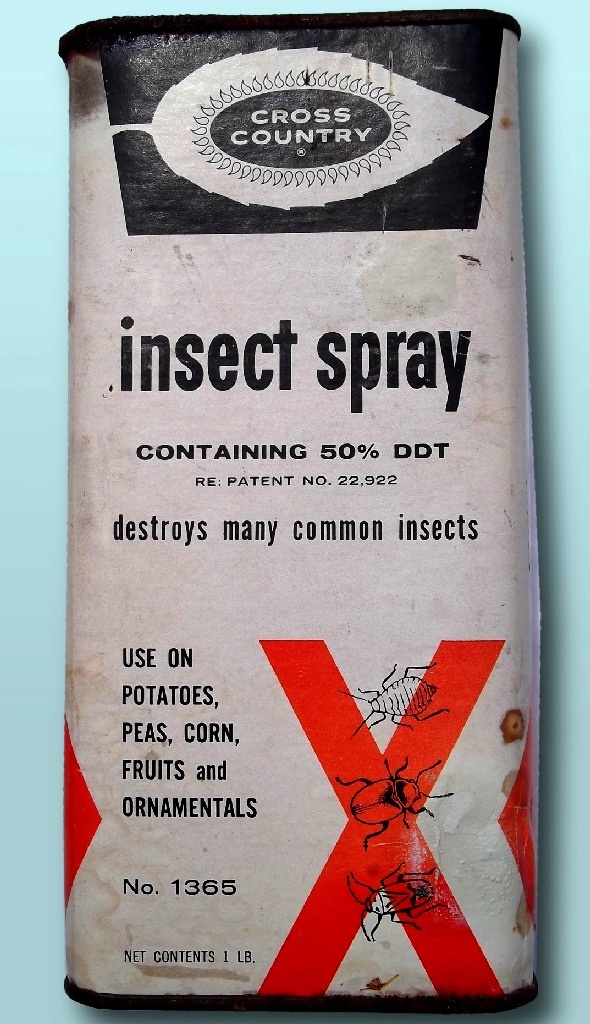

POWDER BOXES - Scientists Commercial product (Powder box, 50 g) containing 10% DDT Dichlordiphenyltrichlorethane; Néocide. Ciba Geigy DDT; "Destroys parasites such as fleas, lice, ants, bedbugs, cockroaches, flies, etc. Néocide Sprinkle caches of vermin and the places where there are insects and their places of passage. Leave the powder in place as long as possible." "Destroy the parasites of man and his dwelling". "Death is not instantaneous, it follows inevitably sooner or later." "French manufacturing"; "harmless to humans and warm-blooded animals" "sure and lasting effect. Odorless.

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline organochlorine known for its insecticidal properties and environmental impacts. First synthesized in 1874, DDT's insecticidal action was discovered by the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939. DDT was used in the second half of World War II to control malaria and typhus among civilians and troops. Müller was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods" in 1948.

By October 1945, DDT was available for public sale in the United States. Although it was promoted by government and industry for use as an agricultural and household pesticide, there were also concerns about its use from the beginning. Opposition to DDT was focused by the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring. It cataloged environmental impacts that coincided with widespread use of DDT in agriculture in the United States, and it questioned the logic of broadcasting potentially dangerous chemicals into the environment with little prior investigation of their environment and health effects. The book claimed that DDT and other pesticides had been shown to cause cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds. Its publication was a seminal event for the environmental movement and resulted in a large public outcry that eventually led, in 1972, to a ban on DDT's agricultural use in the United States.

A worldwide ban on agricultural use was formalized under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, but its limited and still-controversial use in disease vector control continues, because of its effectiveness in reducing malarial infections, balanced by environmental and other health concerns.

Along with the passage of the Endangered Species Act, the United States ban on DDT is a major factor in the comeback of the bald eagle (the national bird of the United States) and the peregrine falcon from near-extinction in the contiguous United States.

From 1950 to 1980, DDT was extensively used in agriculture – more than 40,000 tonnes each year worldwide – and it has been estimated that a total of 1.8 million tonnes have been produced globally since the 1940s. In the United States, it was manufactured by some 15 companies, including Monsanto, Ciba, Montrose Chemical Company, Pennwalt and Velsicol Chemical Corporation. Production peaked in 1963 at 82,000 tonnes per year. More than 600,000 tonnes (1.35 billion pounds) were applied in the US before the 1972 ban. Usage peaked in 1959 at about 36,000 tonnes.

In 2009, 3,314 tonnes were produced for malaria control and visceral leishmaniasis. India is the only country still manufacturing DDT and is the largest consumer. China ceased production in 2007.

In insects DDT opens sodium ion channels in neurons, causing them to fire spontaneously, which leads to spasms and eventual death. Insects with certain mutations in their sodium channel gene are resistant to DDT and similar insecticides.

CROP DUSTING - Not quite, but an attempt to control budworm in spruce in 1955. This airplane is spraying DDT over Baker County, Oregon.

1940s - 1950s

DDT is the best-known of several chlorine-containing pesticides used in the 1940s and 1950s. With pyrethrum in short supply, DDT was used extensively during World War II by the Allies to control the insect vectors of typhus – nearly eliminating the disease in many parts of Europe. In the South Pacific, it was sprayed aerially for malaria and dengue fever control with spectacular effects. While DDT's chemical and insecticidal properties were important factors in these victories, advances in application equipment coupled with competent organization and sufficient manpower were also crucial to the success of these programs.

In 1945, DDT was made available to farmers as an agricultural insecticide and played a role in the final elimination of malaria in Europe and North America.

In 1955, the World Health Organization commenced a program to eradicate malaria in countries with low to moderate transmission rates worldwide, relying largely on DDT for mosquito control and rapid diagnosis and treatment to reduce transmission. The program eliminated the disease in "Taiwan, much of the Caribbean, the Balkans, parts of northern Africa, the northern region of Australia, and a large swath of the South Pacific" and dramatically reduced mortality in Sri Lanka and India.

However, failure to sustain the program, increasing mosquito tolerance to DDT, and increasing parasite tolerance led to a resurgence. In many areas early successes partially or completely reversed, and in some cases rates of transmission increased. The program succeeded in eliminating malaria only in areas with "high socio-economic status, well-organized healthcare systems, and relatively less intensive or seasonal malaria transmission".

DDT was less effective in tropical regions due to the continuous life cycle of mosquitoes and poor infrastructure. It was not applied at all in sub-Saharan Africa due to these perceived difficulties. Mortality rates in that area never declined to the same dramatic extent, and now constitute the bulk of malarial deaths worldwide, especially following the disease's resurgence as a result of resistance to drug treatments and the spread of the deadly malarial variant caused by Plasmodium falciparum.

Eradication was abandoned in 1969 and attention instead focused on controlling and treating the disease. Spraying programs (especially using DDT) were curtailed due to concerns over safety and environmental effects, as well as problems in administrative, managerial and financial implementation. Efforts shifted from spraying to the use of bednets impregnated with insecticides and other interventions.

BANS

In the 1970s and 1980s, agricultural use was banned in most developed countries, beginning with Hungary in 1968 followed by Norway and Sweden in 1970, West Germany and the US in 1972, but not in the United Kingdom until 1984. By 1991 total bans, including for disease control, were in place in at least 26 countries; for example Cuba in 1970, Singapore in 1984, Chile in 1985 and the Republic of Korea in 1986.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which took effect in 2004, put a global ban on several persistent organic pollutants, and restricted DDT use to vector control. The Convention was ratified by more than 170 countries. Recognizing that total elimination in many malaria-prone countries is currently unfeasible absent affordable/effective alternatives, the convention exempts public health use within World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines from the ban. Resolution 60.18 of the World Health Assembly commits WHO to the Stockholm Convention's aim of reducing and ultimately eliminating DDT. Malaria Foundation International states, "The outcome of the treaty is arguably better than the status quo going into the negotiations. For the first time, there is now an insecticide which is restricted to vector control only, meaning that the selection of resistant mosquitoes will be slower than before."

Despite the worldwide ban, agricultural use continued in India, North Korea, and possibly elsewhere as of 2008.

Today, about 3,000 to 4,000 tons of DDT are produced each year for disease vector control. DDT is applied to the inside walls of homes to kill or repel mosquitoes. This intervention, called indoor residual spraying (IRS), greatly reduces environmental damage. It also reduces the incidence of DDT resistance. For comparison, treating 40 hectares (99 acres) of cotton during a typical U.S. growing season requires the same amount of chemical as roughly 1,700 homes.

ENVIRONMENT

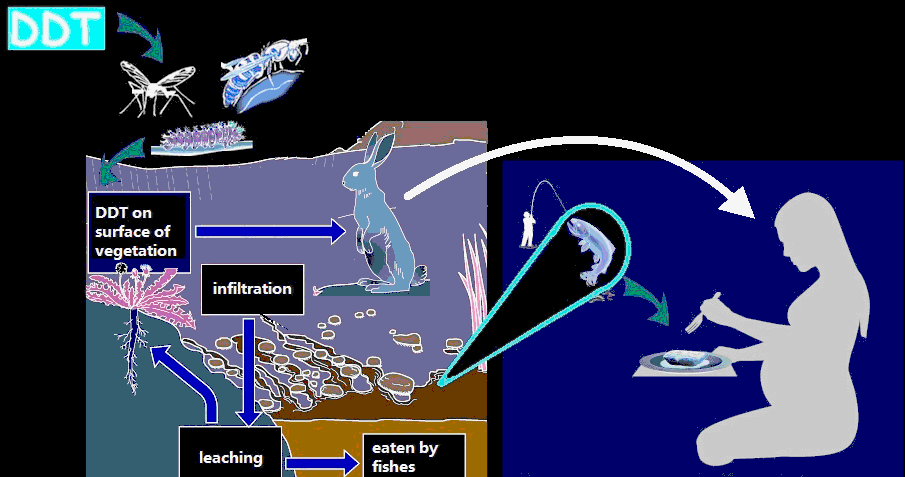

DDT is a persistent organic pollutant that is readily adsorbed to soils and sediments, which can act both as sinks and as long-term sources of exposure affecting organisms. Depending on conditions, its soil half-life can range from 22 days to 30 years. Routes of loss and degradation include runoff, volatilization, photolysis and aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation. Due to hydrophobic properties, in aquatic ecosystems DDT and its metabolites are absorbed by aquatic organisms and adsorbed on suspended particles, leaving little DDT dissolved in the water. Its breakdown products and metabolites, DDE and DDD, are also persistent and have similar chemical and physical properties. DDT and its breakdown products are transported from warmer areas to the Arctic by the phenomenon of global distillation, where they then accumulate in the region's food web.

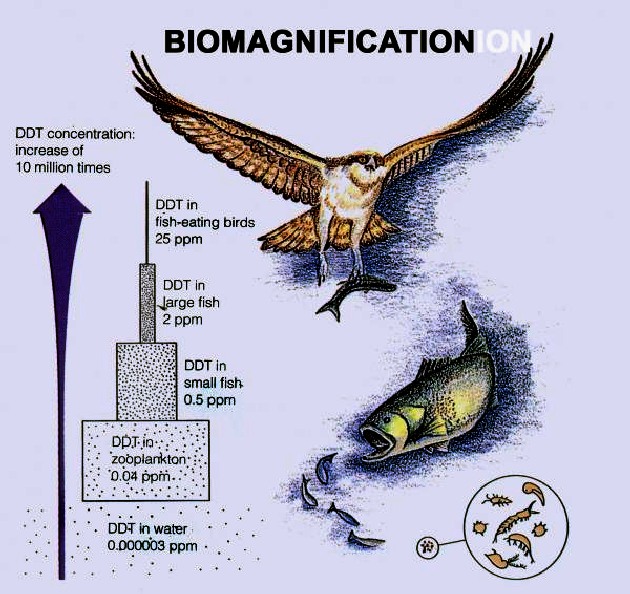

Because of its lipophilic properties, DDT can bioaccumulate, especially in predatory birds. DDT is toxic to a wide range of living organisms, including marine animals such as crayfish, daphnids, sea shrimp and many species of fish. DDT, DDE and DDD magnify through the food chain, with apex predators such as raptor birds concentrating more chemicals than other animals in the same environment. They are stored mainly in body fat. DDT and DDE are resistant to metabolism; in humans, their half-lives are 6 and up to 10 years, respectively. In the United States, these chemicals were detected in almost all human blood samples tested by the Centers for Disease Control in 2005, though their levels have sharply declined since most uses were banned. Estimated dietary intake has declined, although FDA food tests commonly detect it.

HUMAN HEALTH

DDT is an endocrine disruptor. It is considered likely to be a human carcinogen although the majority of studies suggest it is not directly genotoxic. DDE acts as a weak androgen receptor antagonist, but not as an estrogen.

DDT is classified as "moderately toxic" by the US National Toxicology Program (NTP) and "moderately hazardous" by WHO, based on the rat oral LD50 of 113 mg/kg. Indirect exposure is considered relatively non-toxic for humans.

Primarily through the tendency for DDT to buildup in areas of the body with high lipid content, chronic exposure can affect reproductive capabilities and the embryo or fetus.

CARCINOGENICITY

A 2005 Lancet review stated that occupational DDT exposure was associated with increased pancreatic cancer risk in 2 case control studies, but another study showed no DDE dose-effect association. Results regarding a possible association with liver cancer and biliary tract cancer are conflicting: workers who did not have direct occupational DDT contact showed increased risk. White men had an increased risk, but not white women or black men. Results about an association with multiple myeloma, prostate and testicular cancer, endometrial cancer and colorectal cancer have been inconclusive or generally do not support an association. A 2017 review of liver cancer studies concluded that "organochlorine pesticides, including DDT, may increase hepatocellular carcinoma risk."

A 2009 review, whose co-authors included persons engaged in DDT-related litigation, reached broadly similar conclusions, with an equivocal association with testicular cancer. Case–control studies did not support an association with leukemia or lymphoma.

MALARIA

When it was introduced in World War II, DDT was effective in reducing malaria morbidity and mortality. WHO's anti-malaria campaign, which consisted mostly of spraying DDT and rapid treatment and diagnosis to break the transmission cycle, was initially successful as well. For example, in Sri Lanka, the program reduced cases from about one million per year before spraying to just 18 in 1963 and 29 in 1964. Thereafter the program was halted to save money and malaria rebounded to 600,000 cases in 1968 and the first quarter of 1969. The country resumed DDT vector control but the mosquitoes had evolved resistance in the interim, presumably because of continued agricultural use. The program switched to malathion, but despite initial successes, malaria continued its resurgence into the 1980s.

Malaria remains the primary public health challenge in many countries. In 2015, there were 214 million cases of malaria worldwide resulting in an estimated 438,000 deaths, 90% of which occurred in Africa. DDT is one of many tools to fight the disease. Its use in this context has been called everything from a "miracle weapon that is like Kryptonite to the mosquitoes," to "toxic colonialism".

ALTERNATIVES

Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, e.g. malathion and bendiocarb, respectively, are more expensive than DDT per kilogram and are applied at roughly the same dosage. Pyrethroids such as deltamethrin are also more expensive than DDT, but are applied more sparingly (0.02–0.3 g/m2 vs 1–2 g/m2), so the net cost per house is about the same.

BIO ACCUMULATION

Bioaccumulation of POPs is typically associated with the compounds high lipid solubility and ability to accumulate in the fatty tissues of living organisms for long periods of time. Persistent chemicals tend to have higher concentrations and are eliminated more slowly. Dietary accumulation or bioaccumulation is another hallmark characteristic of POPs, as POPs move up the food chain, they increase in concentration as they are processed and metabolized in certain tissues of organisms. The natural capacity for animals gastrointestinal tract concentrate ingested chemicals, along with poorly metabolized and hydrophobic nature of POPs makes such compounds highly susceptible to bioaccumulation. Thus POPs not only persist in the environment, but also as they are taken in by animals they bioaccumulate, increasing their concentration and toxicity in the environment.

TOXIC SPONGE - This is just a small sample of the plastic packaging that you will find in retails stores all over the world. A good proportion of this packaging - around 8 millions tons a year, will end up in our oceans, in the gut of the fish we eat, in the stomachs of seabirds and in the intestines of whales and other marine mammals, taking with it POPs that will end up in the food you eat. Copyright photograph © 22-7-17 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd, all rights reserved.

GLOBAL WASTE PROBLEM - The above views of planet earth as global views show us the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific ocean gyres and estimates of plastic waste in (thousands) numbers of pieces of plastic waste per square kilometer of sea. The Pacific Ocean gyres are held to be the worst at the moment.

LINKS & REFERENCE

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/01/150109-oceans-plastic-sea-trash-science-marine-debris/ http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/plastic-waste-in-ocean-to-increase-tenfold-by-2020-10042613.html https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_debris http://britishseafishing.co.uk/microplastics-and-ocean-pollution/ http://wef.ch/plasticseconomy

ABS - BIOMAGNIFICATION - BP DEEPWATER - CANCER - CARRIER BAGS - CLOTHING - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING NETS FUKUSHIMA - HEAVY METALS - MARINE LITTER - MICROBEADS - MICRO PLASTICS - NYLON - OCEAN GYRES - OCEAN WASTE PACKAGING - PCBS - PET - PLASTIC - PLASTICS - POLYCARBONATE - POLYSTYRENE - POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS PVC - SHOES - SINGLE USE - SOUP - STRAWS - WATER

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774) 2018. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom. COFL is a charity without share capital.

|