|

CONTAMINATED

DRINKING WATER

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

WORLD

MAP

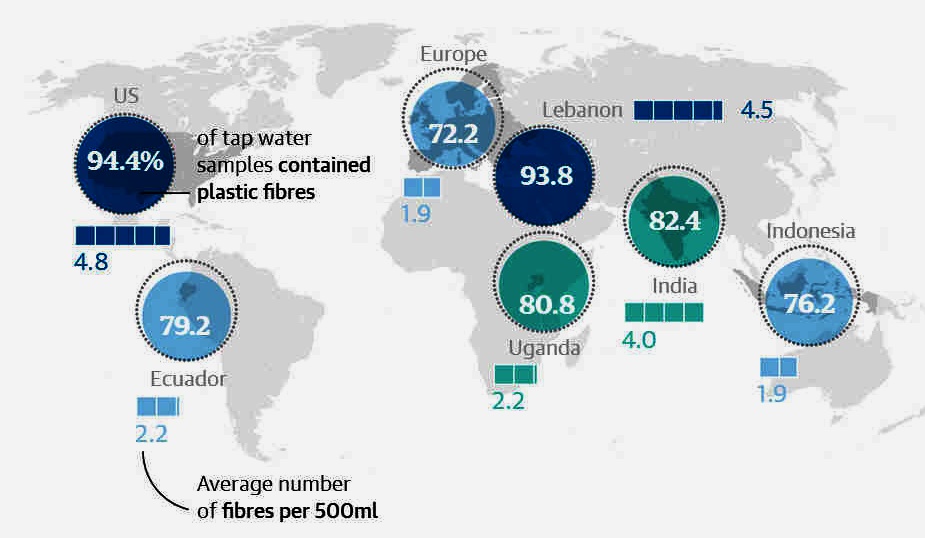

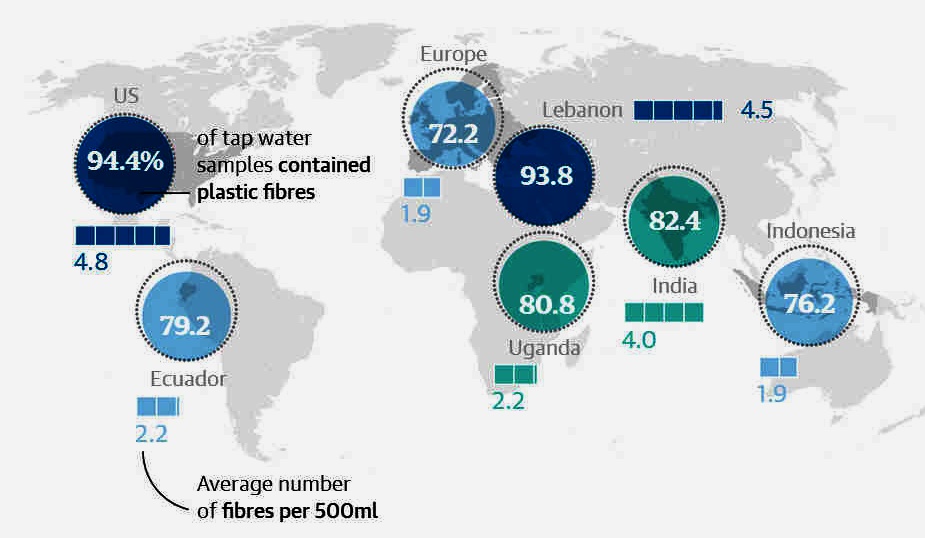

- This map shows the percentage of sampled water that

contained plastic fibres

around the world, demonstrating that this is a serious

international problem. In terms of sustainability, the

widespread contamination must be seen as a long term health

risk for all humans, the end result of which is a potentially carcinogenic

supplement to our diets from biomagnification

that at the moment we seem powerless to avoid.

THE

GUARDIAN 6 SEPTEMBER 2017

Microplastic contamination has been found in tap

water in countries around the world, leading to calls from scientists for urgent research on the implications for health.

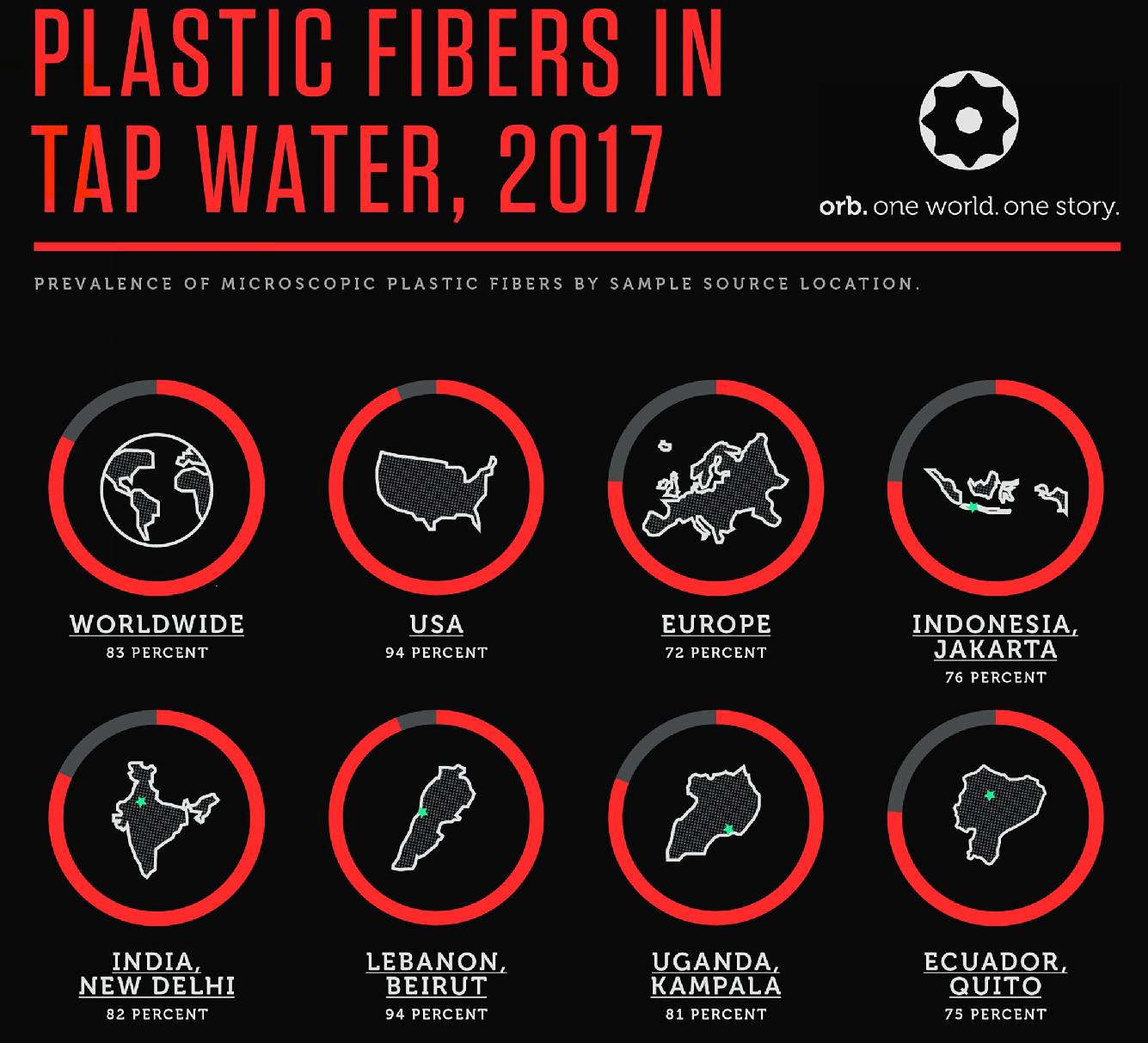

Scores of tap water samples from more than a dozen nations were analysed by scientists for an investigation by Orb Media, who shared the findings with the Guardian. Overall, 83% of the samples were contaminated with plastic fibres.

The US had the highest contamination rate, at 94%, with plastic fibres found in tap water sampled at sites including Congress buildings, the US Environmental Protection Agency’s headquarters, and Trump Tower in

New

York. Lebanon and India had the next highest rates.

European nations including the UK, Germany and France had the lowest contamination rate, but this was still 72%. The average number of fibres found in each 500ml sample ranged from 4.8 in the US to 1.9 in Europe.

The new analyses indicate the ubiquitous extent of microplastic contamination in the global environment. Previous work has been largely focused on

plastic pollution in the

oceans, which suggests people are eating microplastics via contaminated seafood.

“We have enough data from looking at wildlife, and the impacts that it’s having on wildlife, to be concerned,” said Dr Sherri Mason, a microplastic expert at the State University of New York in Fredonia, who supervised the analyses for Orb. “If it’s impacting [wildlife], then how do we think that it’s not going to somehow impact us?”

A separate small study in the Republic of Ireland released in June also found microplastic contamination in a handful of tap

water and well samples. “We don’t know what the [health] impact is and for that reason we should follow the precautionary principle and put enough effort into it now, immediately, so we can find out what the real risks are,” said Dr Anne Marie Mahon at the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, who conducted the research.

Mahon said there were two principal concerns: very small plastic particles and the chemicals or pathogens that microplastics can harbour. “If the fibres are there, it is possible that the nanoparticles are there too that we can’t measure,” she said. “Once they are in the nanometre range they can really penetrate a cell and that means they can penetrate organs, and that would be worrying.” The Orb analyses caught particles of more than 2.5 microns in size, 2,500 times bigger than a nanometre.

PLASTIC

ON TAP - The average number of fibres found in each 500ml sample

of water ranged from 4.8 in the US to 1.9 in Europe. The irresistible

conclusion is that waste recycling in Europe is more

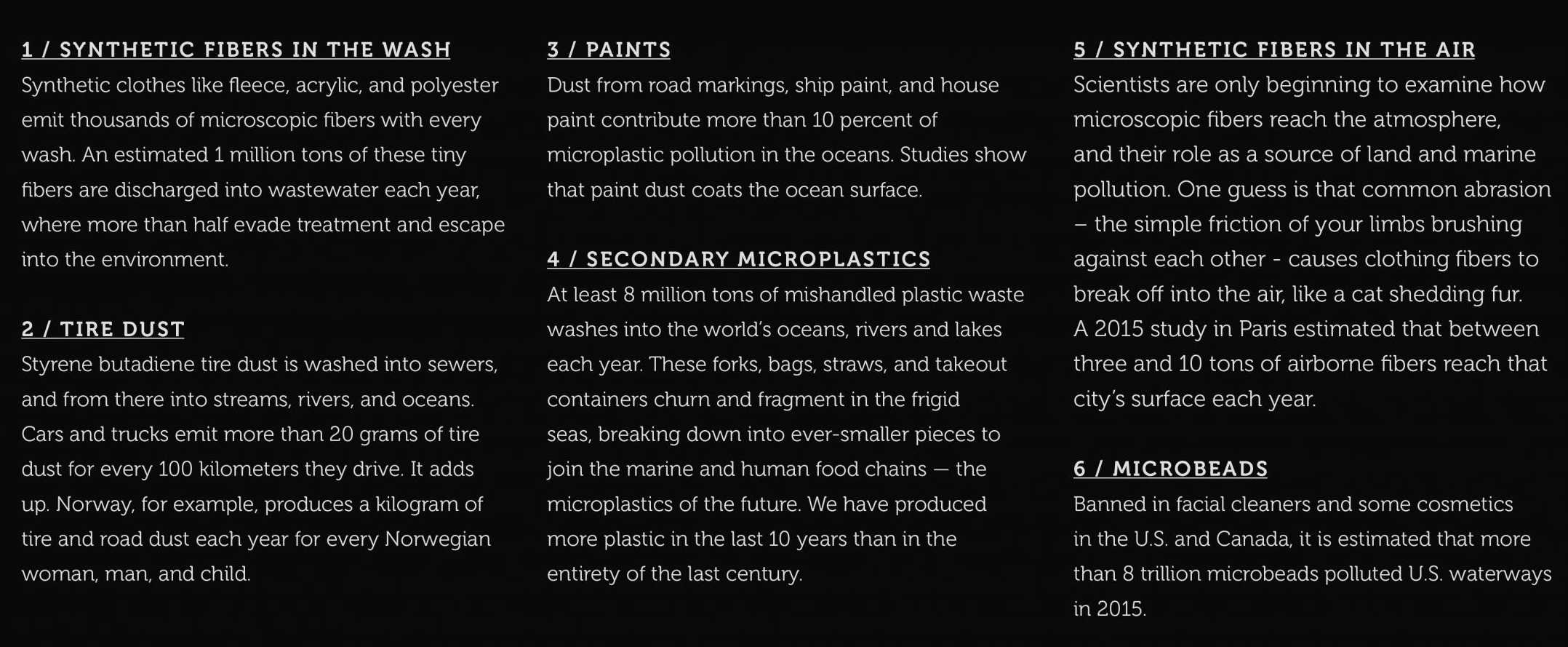

effective, although why that might be is not yet known. Chemicals from plastics are a constant part of our daily diet. We generally assume the water bottle holding that pure spring water, the microwave-safe plastic bowl we prepare our meals in, or the styrofoam cup holding a hot drink is there protecting our food and drinks. Rather than acting as a completely inert barrier, these plastics are breaking down and leaching chemicals, including endocrine-disrupting plasticizers like BPA or phthalates, flame retardants, and even toxic heavy metals that are all absorbed into our diets and bodies — Scott Belcher, Ph.D. Research Professor, North Carolina State University

Microplastics can attract bacteria found in

sewage, Mahon said: “Some studies have shown there are more harmful pathogens on

microplastics downstream of wastewater treatment plants.”

Microplastics are also known to contain and absorb toxic chemicals and research on wild animals shows they are released in the body. Prof Richard Thompson, at

Plymouth

University, UK, told Orb: “It became clear very early on that the plastic would release those chemicals and that actually, the conditions in the gut would facilitate really quite rapid release.” His research has shown microplastics are found in a third of

fish caught in the

UK.

The scale of global microplastic contamination is only starting to become clear, with studies in Germany finding fibres and fragments in all of the 24 beer brands they tested, as well as in honey and

sugar. In

Paris in 2015, researchers discovered microplastic falling from the

air, which they estimated deposits three to 10 tonnes of fibres on the city each year, and that it was also present in the air in people’s homes.

This research led Frank Kelly, professor of environmental health at King’s College

London, to tell a UK parliamentary inquiry in 2016: “If we breathe them in they could potentially deliver chemicals to the lower parts of our lungs and maybe even across into our circulation.” Having seen the Orb data, Kelly told the

Guardian that research is urgently needed to determine whether ingesting

plastic particles is a health risk.

ROZALIA

PROJECT PICTURE - A magnified image of clothing microfibres from washing machine effluent. One study found that a fleece jacket can shed as many as 250,000 fibres per wash.

The new research tested 159 samples using a standard technique to eliminate contamination from other sources and was performed at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. The samples came from across the world, including from Uganda, Ecuador and Indonesia.

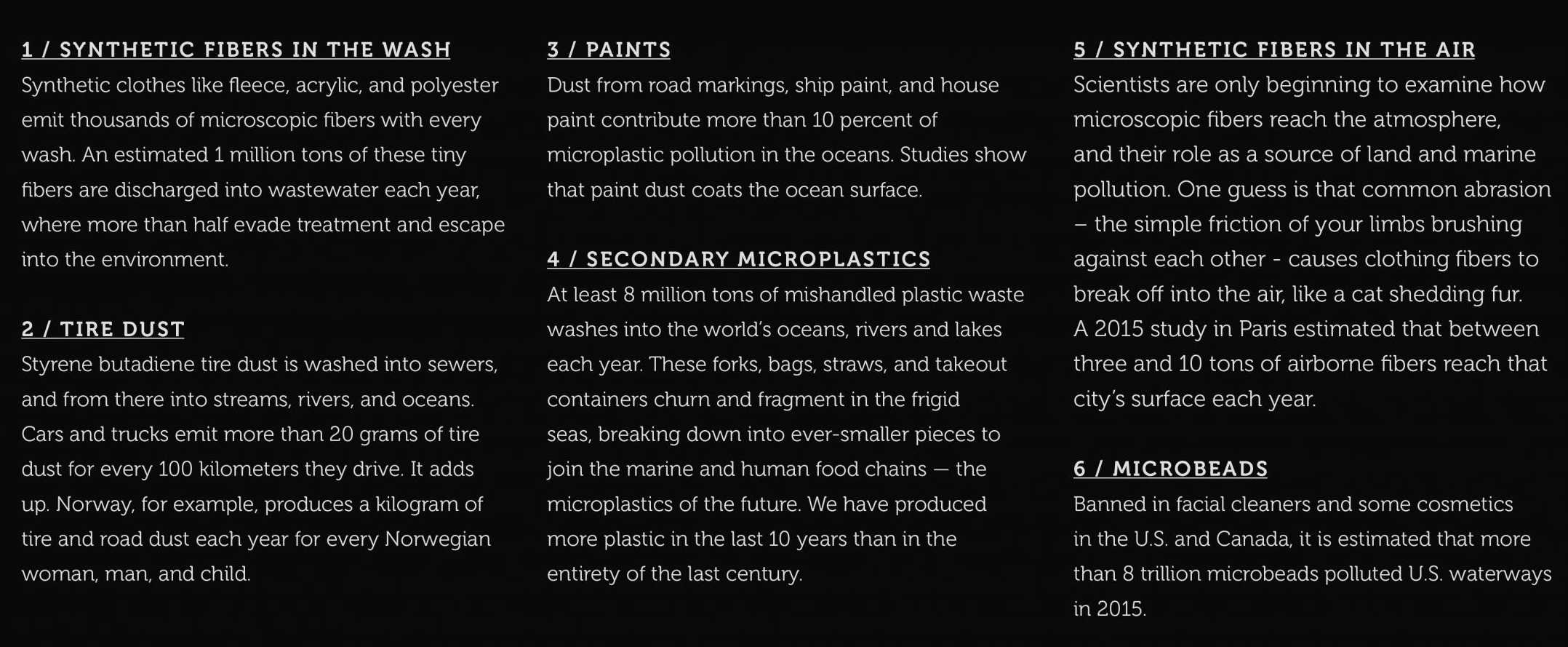

How microplastics end up in drinking water is for now a mystery, but the atmosphere is one obvious source, with fibres shed by the everyday wear and tear of clothes and carpets. Tumble dryers are another potential source, with almost 80% of US households having dryers that usually vent to the open

air.

“We really think that the lakes [and other water bodies] can be contaminated by cumulative atmospheric inputs,” said Johnny Gasperi, at the University Paris-Est Créteil, who did the Paris studies. “What we observed in Paris tends to demonstrate that a huge amount of fibres are present in atmospheric fallout.”

Plastic fibres may also be flushed into water systems, with a recent study finding that each cycle of a washing machine could release 700,000 fibres into the environment. Rains could also sweep up microplastic pollution, which could explain why the household wells used in Indonesia were found to be contaminated.

In Beirut, Lebanon, the water supply comes from natural springs but 94% of the samples were contaminated. “This research only scratches the surface, but it seems to be a very itchy one,” said Hussam Hawwa, at the environmental consultancy Difaf, which collected samples for Orb.

Current standard water treatment systems do not filter out all of the microplastics, Mahon said: “There is nowhere really where you can say these are being trapped 100%. In terms of fibres, the diameter is 10 microns across and it would be very unusual to find that level of filtration in our drinking water systems.”

Bottled water may not provide a microplastic-free alternative to tapwater, as the they were also found in a few samples of commercial bottled water tested in the US for Orb.

Almost 300m tonnes of plastic is produced each year and, with just 20% recycled or incinerated, much of it ends up littering the air, land and sea. A report in July found 8.3bn tonnes of plastic has been produced since the 1950s, with the researchers warning that plastic waste has become ubiquitous in the environment.

“We are increasingly smothering ecosystems in plastic and I am very worried that there may be all kinds of unintended, adverse consequences that we will only find out about once it is too late,” said Prof Roland Geyer, from the University of

California and Santa Barbara, who led the study.

Mahon said the new tap water analyses raise a red flag, but that more work is needed to replicate the results, find the sources of contamination and evaluate the possible health impacts.

She said plastics are very useful, but that management of the waste must be drastically improved: “We need plastics in our lives, but it is us that is doing the damage by discarding them in very careless ways.”

By Damian

Carrington

THE

TERRAMAR PROJECT SEPTEMBER 8 2017 - A DAILY DOSE OF

PLASTIC

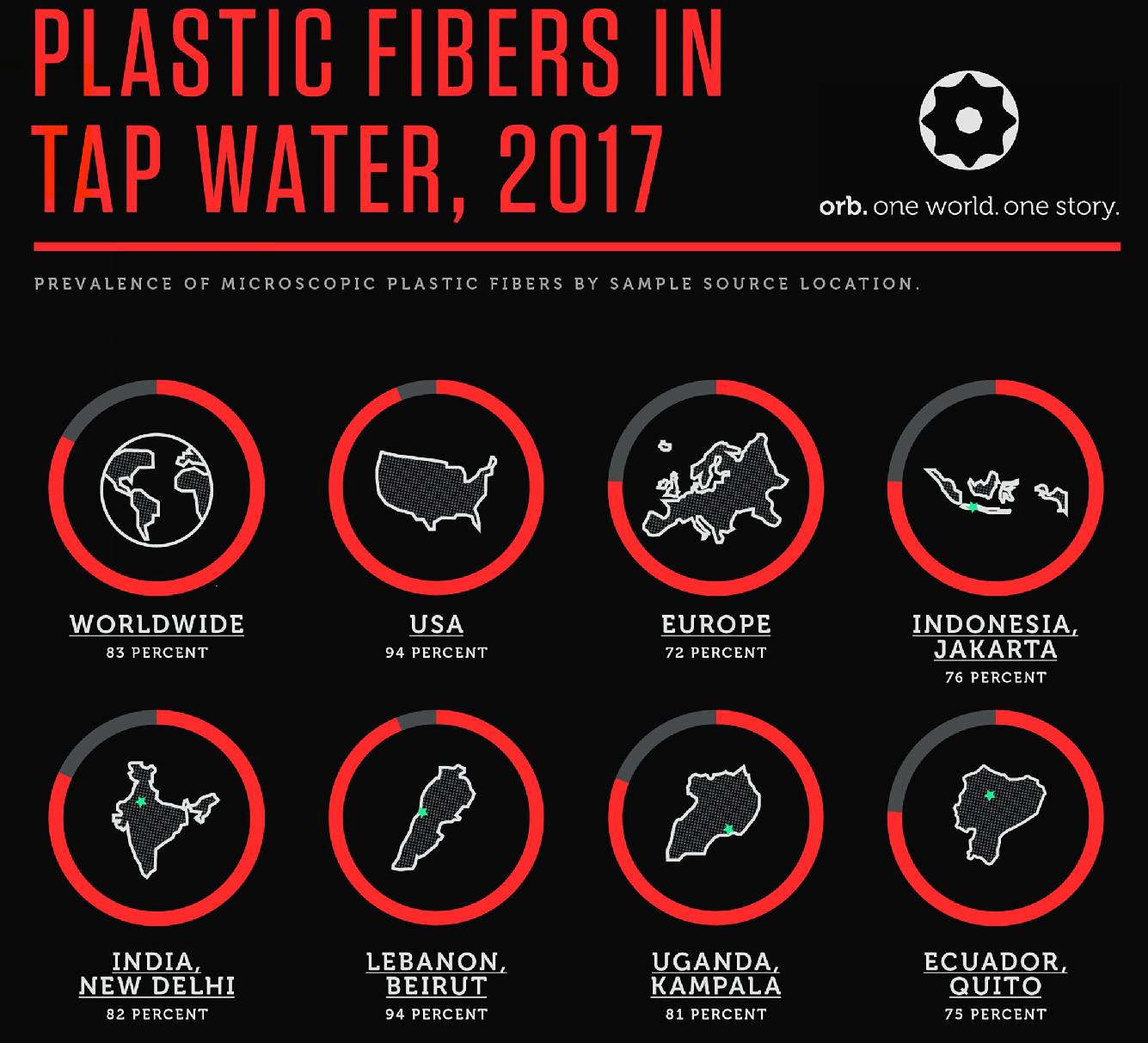

New Study Shows Billions of People Are Drinking Tap Water Contaminated by Microplastics

Microplastic contamination has been found in tap water in countries around the world, leading to calls from scientists for urgent research on the implications for health.

Scores of tap water samples from more than a dozen nations were analysed by scientists for an investigation by Orb Media, who shared the findings with

the

Guardian. Overall, 83% of the samples were contaminated with plastic fibres.

The US had the highest contamination rate, at 94%, with plastic fibres found in tap water sampled at sites including Congress buildings, the

US Environmental Protection Agency’s headquarters, and

Trump Tower in New York. Lebanon and

India had the next highest rates.

European nations including the UK, Germany and

France had the lowest contamination rate, but this was still 72%. The average number of fibres found in each 500ml sample ranged from 4.8 in the US to 1.9 in

Europe.

The new analyses indicate the ubiquitous extent of microplastic contamination in the global environment. Previous work has been largely focused on plastic pollution in the

oceans, which suggests people are eating microplastics via contaminated seafood.

PHILIPPINES - Dagupan. A young boy climbs over plastic debris in a 50-year-old dump overlooking the ocean in this seaside town. Most of the biodegradable items have long since rotted, leaving a mountain of multicolored plastics that float out to sea on the coastal winds.

ARE

WE SAFE? -

Chemicals from plastics are a constant part of our daily diet. We generally assume the water bottle holding that pure spring water, the microwave-safe plastic bowl we prepare our meals in, or the styrofoam cup holding a hot drink is there protecting our food and drinks. Rather than acting as a completely inert barrier, these plastics are breaking down and leaching chemicals, including endocrine-disrupting plasticizers like BPA or phthalates, flame retardants, and even toxic heavy metals that are all absorbed into our diets and bodies — Scott Belcher, Ph.D. Research Professor, North Carolina State University

ORB

- INVISIBLES, THE PLASTIC INSIDE US

It is everywhere: the most enduring, insidious, and intimate product in the world.

From the soles of your shoes to the contact lenses in your eyes, the phone in your pocket to the food in your refrigerator, the evidence is unmistakable: We are living in The Plastic Age.

Plastic frees us, improving daily life in almost uncountable ways.

And plastic imprisons us in waste and microscopic pollution.

Recent studies have shown the shocking extent of plastics in the world’s oceans and lakes. Orb Media followed with a new question: If microscopic plastic is in oceans, lakes, and rivers, is it in drinking water as well?

In the first public scientific study of its kind, we found previously unknown plastic contamination in the tap water of cities around the world.

Microscopic plastic fibers are flowing out of taps from New York to New Delhi, according to exclusive research by Orb and a researcher at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. From the halls of the U.S. Capitol to the shores of Lake Victoria in Uganda, women, children, men, and babies are consuming plastic with every glass of water.

More than 80 percent of the samples we collected on five continents tested positive for the presence of plastic fibers.

Microplastics — tiny plastic fibers and fragments — aren’t just choking the ocean; they have infested the world’s drinking water.

Why should you care? Microplastics have been shown to absorb toxic chemicals linked to cancer and other illnesses, and then release them when consumed by fish and mammals.

Scientists say these microscopic fibers might originate in the everyday abrasion of clothes, upholstery, and carpets. They could reach your household tap by contaminating local water sources, or treatment and distribution systems. But no one knows, and no specific procedures yet exist for filtering or containing them.

If plastic fibers are in your water, experts say they’re surely in your food as well — baby formula, pasta, soups, and sauces, whether from the kitchen or the grocery. Plastic fibers may leaven your pizza crust, and a forthcoming study says it’s likely in the craft beer you’ll drink to chase the pepperoni down.

It gets worse. Plastic is all but indestructible, meaning plastic waste doesn’t biodegrade; rather, it only breaks down into smaller pieces of itself, even down to particles in nanometer scale — one-one thousandth of one-one thousandth of a millimeter.

Studies show particles of that size can migrate through the intestinal wall and travel to the lymph nodes and other bodily organs.

What does plastic in tap water mean for human health, how did it get there, and what can people do about it? We went looking for answers in a ten-month investigation across six continents.

A

HEAP OF TROUBLE - Dagupan, Philippines. Mayor Belen Fernandez watches the city’s 50 year-old dump smolder. The dump routinely sends plastic sailing out to the South China Sea. Fernandez has vowed to return the beach to its pristine form and convert the mountain of waste into fuel to power the city’s fishing fleet and motorcycle taxis.

The only way to keep plastic out of the air, water, and soil is to radically rethink its design, uses, sale, and disposal. There’s a lot of catching up to do. Here are some ways people around the world are working to change this grim global reality.

Waste-to-Energy turns plastic and organic waste into gas and liquid fuel using a variety of technologies. The global waste-to-energy market is forecast to grow into a USD$33 billion industry by 2023.

In the “Circular Economy” model, manufacturers and designers ensure that packaging and materials can be easily recycled and repurposed. Today, more than half of all plastic packaging can’t be recycled.

New Materials: Leading brands and new startups are working to design synthetic fabrics that won’t shed fibers into the air and water. Bolt Threads, in California, is using proteins from spider silk to create a strong, stretchy fabric they hope will replace synthetic fleece. A Japanese company, Spiber, also plans to serve the outdoor apparel industry through spider silk. Meanwhile, startup NewLight Technologies has created a plastic called Air Carbon from greenhouse gases produced by cattle and landfills instead of from oil. “We can’t say enough about this material,” said Joe Burkhart of the U.S. furniture maker KI. “It really has potential to impact the world on a major scale.”

Household Solutions. Designers around the world are looking at ways consumers can reduce plastic emissions. One product, the Cora Ball, catches up to 35 percent of the fibers released in a single load of laundry, before they’re discharged into treatment facilities, rivers, and lakes.

Each of these solutions depends on individuals, companies, and governments taking responsibility for the plastic waste generated by their purchases, their product designs, and their attitude to environmental protection.

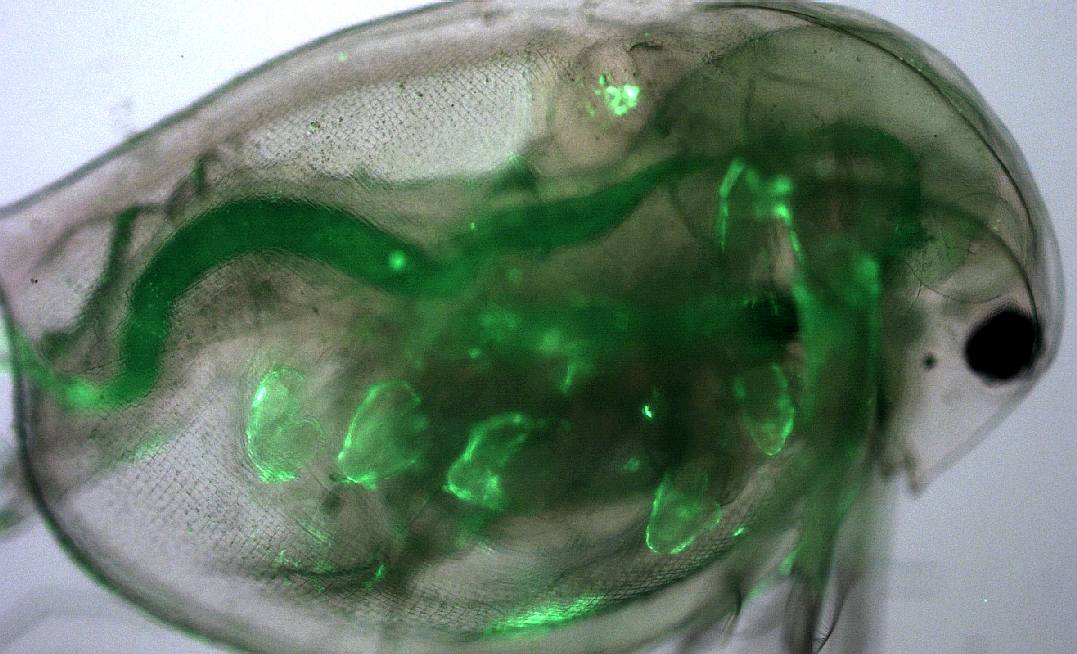

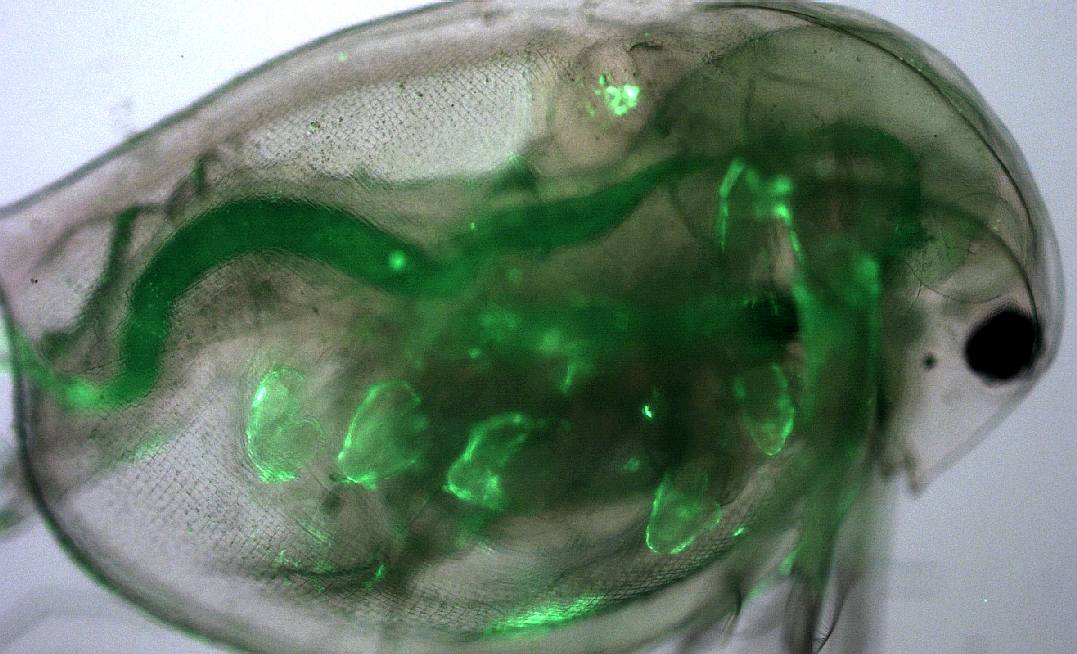

EXETER

- England. Polystyrene particles less than 50 nanometers long (in light fluorescent green) have infiltrated the gastrointestinal tract, antenna, and thoracic appendages of this freshwater

plankter, Daphnia magna. Plankton like these are the bedrock of the marine food chain. Research is just beginning on the accumulation of nanometer-scale pollution in wildlife. No analytical methods exist to identify nanoplastics in food. Plastic embedded in tiny plankton wind up in fish, which are eaten by bigger fish, which are eaten by us. This tiny plankter’s plastic problem is your problem, too. (Photo: Corin

Liddle)

WHAT NOW

Almost no one asks to have plastic or plastic-related chemicals in their body. No brand or manufacturer ever seeks permission to put them there. Regulators, industry, and independent researchers make slow and sometimes contradictory calls over how much of a given pollutant might be safe. That delay can be costly: By the time the U.S. phased out use of the fire retardant PDBE in electronics, baby clothes, and furniture, exposure to the chemical had chopped 11 million IQ points off the intellectual abilities of tens of thousands of U.S. children, at a cost of USD$266 billion and immeasurable heartache.

Fibers in tap water, then, are both a discovery and a marker — a visceral sign of how far plastic has penetrated human life and human anatomy. We can't see the long-chain molecules of pollutants like polyfluoroalkyl chemicals, even if they do reside in more than 98 percent of the population. But when fibers are filtered in a laboratory and enlarged by a microscope, the contamination becomes real.

The first studies into the health effects of microscopic plastics on humans are only just now beginning; there’s no telling if or when governments might establish a “safe” threshold for plastic in water and food. Even farther away are studies of human exposure to nano-scale plastic particles, plastic measured in the millionths of a millimeter.

Municipalities are only beginning to reckon with their role in fiber pollution. Slowing the wastewater treatment process would allow facilities to capture more plastic fibers, said Kartik Chandran, an environmental engineer at Columbia University and a 2015 MacArthur Fellow. But this would likely require the construction of additional treatment facilities and would increase capital costs, he said.

In 1986, K. Eric Drexler, a pioneer in the field of nanotechnology, posited the “Grey Goo Problem,” a doomsday scenario in which tiny robots self-replicate so quickly, and consume so many natural resources, that they extinguish most life on Earth. The computer scientist Bill Joy, a co-founder of Sun Microsystems, gave new fire to this hypothetical in a 2000 essay, “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” that called for curbs on some research into genetics, nanotechnology, and robots.

But what if we don’t need supercomputers and self-breeding robots to wreck the planet? The twin plagues of plastic contamination and climate change show that all it might take is cheap oil, great chemistry, rising living standards, and marvelous profits. The story of the Plastic Age doesn’t end well.

“Since the problem of plastic was created exclusively by human beings through our indifference, it can be solved by human beings by paying attention to it,” Muhammad Yunus, the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, told Orb. “Now what we need is a determination to get it done — before it gets us.”

By Chris Tyree & Dan Morrison

BIOMAGNIFICATION - This planktonic arrow worm, Sagitta setosa, has eaten a blue plastic fibre about 3mm long. Plankton support the entire marine food

chain from where at each stage the plastic builds up before

ending up as fish on our plates.

ABOUT

ORB

What

is Orb? According to their website it is the one unique planet we live on and the

stories about our world.

Orb claim to produce a new kind of journalism that challenges the way people see the world by giving the full picture instead of selected fragments, with the aim of bringing us [people] together around the things we share.

Their website tells that Orb is built on three core premises:

1. Our world is interconnected. As individuals and communities around the world, we are dependent upon one another for our health,

well-being and success.

2. Trans-national, cross-cultural collaboration is key to managing our global challenges and opportunities.

3.

The information we have defines the individual actions we take that ultimately shape our world.

divided

into eight general categories:

1. Food

2.

Water

3.

Energy

4.

Health

5.

Education

6.

Environment

7.

Trade and

8.

Governance

Orb aim to categorize their journalism using the globally recognized framework of the

United

Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals to foster learning and collaboration around these what are or should be Global Goals,

such as blue growth and a circular

economy.

Contact

Orb: +1.202.363.1657

MARK

BROWN Ph.D. - "Whenever you fractionalize a problem, as with the plastic industry not being held responsible for their particular types of waste, there's capacity for that industry then to blame another. So it's waste management; it's not the producer's fault. It's the sewage treatment people’s fault. It's not the actual clothing manufacturer's fault. It's the people who've got the washing machine’s fault. It's somebody else's fault. Generally speaking, it's all of our fault."

— Senior Research Associate, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences,

University of New South Wales

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://orbmedia.org/stories/Invisibles_plastics

http://theterramarproject.org/thedailycatch/daily-dose-plastic-new-study-shows-billions-people-drinking-tap-water-contaminated-microplastics/

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/sep/06/plastic-fibres-found-tap-water-around-world-study-reveals

https://www.theguardian.com/profile/damiancarrington

http://wef.ch/plasticseconomy

ABS

- BIOMAGNIFICATION

- BP DEEPWATER - CANCER

- CARRIER BAGS

- CLOTHING - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING

NETS

FUKUSHIMA - HEAVY

METALS - MARINE LITTER

- MICROBEADS

- MICRO

PLASTICS - NYLON - OCEAN GYRES

- OCEAN WASTE

PACKAGING - PCBS

-

PET - PLASTIC

- PLASTICS

- POLYCARBONATE

- POLYSTYRENE

- POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS

PVC - SHOES

- SINGLE USE

- SOUP - STRAWS - WATER

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2018. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital.

|