|

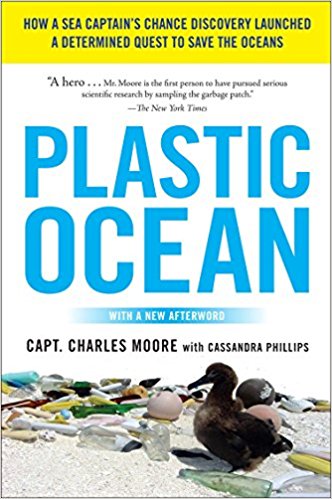

CAPTAIN

CHARLES MOORE

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

THE

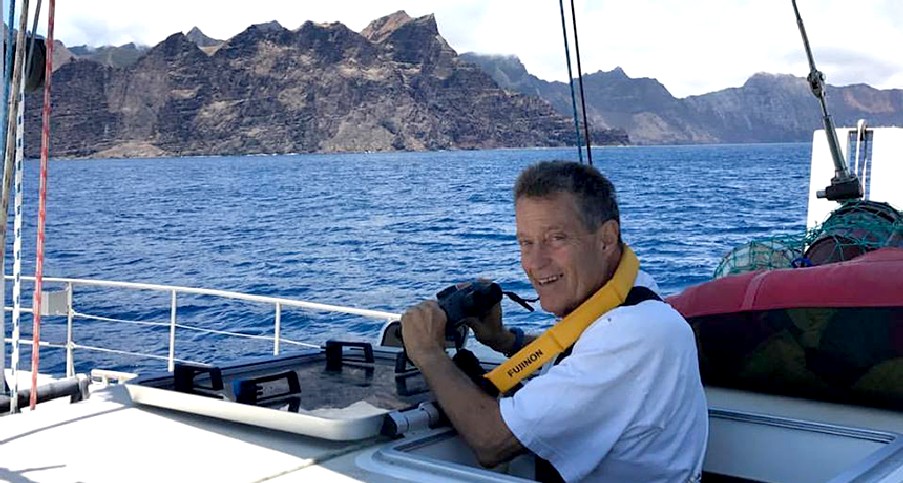

HAT - This famous picture

says it all for us. Captain Charles Moore holds up a sample of

seawater from the pacific ocean, his expression as he eyes the

glass jar sitting on a rolling boat, coupled with the hat that

shades him from the burning sun, tells us all we need to know.

In 1997 Californian sailor,

Charles Moore, was heading home from a sailing race in

Hawaii and decided to take a shortcut across the edge of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (a region often avoided by seafarers).

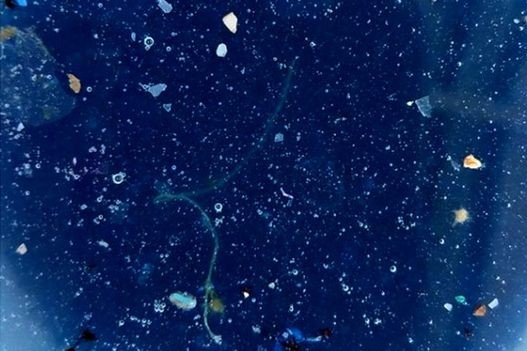

Here he came upon an enormous stretch of floating debris. Throughout the week it took him to traverse the area, there was always some piece of plastic bobbing by: a bottle cap, a toothbrush, a cup, a bag, and a torrent of unidentifiable pieces of plastic bits. Moore sensed there was something terribly wrong here. Two years later, he returned with a fine-mesh net, and discovered, floating beneath the surface, a multicoloured multitude of small plastic flecks and particles, like snowflakes or

fish food. Moore had identified what is now called

“the Great Pacific Garbage

Patch,” an area in the central North Pacific Ocean that is larger than the territory of

France or Texas, which contains exceptionally high concentrations of marine trash.

The

importance of Captain Moore's discovery for mankind cannot be

overstated. More importantly, the inquisitiveness and tenacity

of the sailor is amazing. Science is about observation and

recording. Charles observed what many must have seen before

him, and then did something about it. He pioneered ocean

plastic research and did and is doing his best to make people

aware of it, where awareness is key.

The fact that plastic hardly breaks down is well-known, but rarely talked about. Plastic does not biodegrade, as microbes haven’t evolved to feed on it. It can photo-degrade, however, meaning that sunlight causes its polymer chains to break down into smaller and smaller pieces, a process catalyzed by friction, as when pieces are blown across a beach or rolled by waves. The same process is in play when pieces of rock are rounded by

ocean waves. It is this type of frictional erosion that accounts for the majority of unidentifiable flecks and fragments making up the massive plastic soup at the heart of the Pacific.

Captain Moore is quoted as saying: “As I gazed from the deck at the surface of what ought to have been a pristine ocean,” Moore later wrote in an essay for Natural History, “I was confronted, as far as the eye could see, with the sight of plastic. It seemed unbelievable, but I never found a clear spot. In the week it took to cross the subtropical high, no matter what time of day I looked, plastic debris was floating everywhere: bottles, bottle caps, wrappers, fragments.” An oceanographic colleague of Moore’s dubbed this floating junk yard “the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” and despite Moore’s efforts to suggest different metaphors — “a swirling sewer,” “a superhighway of trash” connecting two “trash cemeteries” — “Garbage Patch” appears to have stuck.

Captain Moore’s research revealed six times more plastic in the area than plankton. It was also discovered that 80 percent of the debris had initially been discarded on land – a finding later confirmed by the

United Nations Environmental Program. Wind blows the plastic through streets and from landfills. It makes its way into rivers, streams and storm drains, then rides the tides and currents out to sea, finally ending up in an ocean gyre. And the trash-vortex Moore discovered isn’t the only one – the planet has six additional major tropical oceanic gyres, all of them swirling with debris.

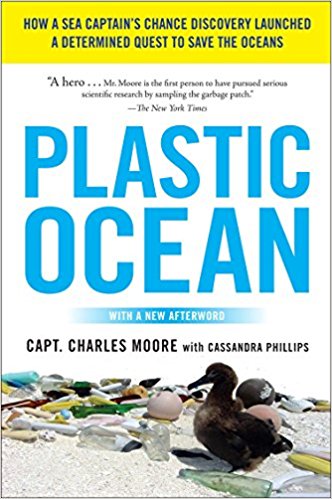

Moore is the founder of the Algalita Marine Research and Education in Long Beach, California, and currently works there.

In 2008 the Foundation organized the JUNK Raft project, to "creatively raise awareness about plastic debris and pollution in the ocean", and specifically the Great Pacific Garbage Patch trapped in the North Pacific Gyre, by sailing 2,600 miles across the Pacific Ocean on a 30-foot-long (9.1 m) raft made from an old Cessna 310 aircraft fuselage and six pontoons filled with 15,000 old plastic bottles. Crewed by Dr. Marcus Eriksen of the Foundation, and film-maker Joel Paschal, the raft set off from Long Beach, California on 1 June 2008, arriving in Honolulu, Hawaii on 28 August 2008. On the way, they gave valuable water supplies to Ocean rower Roz Savage, also on an environmental awareness voyage.

Plastic now forms part of our planet’s food chain. The problem is that nothing in the food chain can digest it. Plastic ends up in the bellies of all kinds of sea creatures – from fish, to turtles, to albatrosses. According to the

United Nations Environment Program, plastic is killing a million seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals and turtles every year. And this is in addition to the deaths by entanglement caused by six-pack rings and discarded synthetic

fishing lines and nets. They also clog animals’ throats and digestive tracts, leading to fatal constipation. One wonders what

Charles

Darwin would have thought of the albatross babies fed bellyfuls of plastic by their albatross parents, who soar out over the vast, polluted ocean collecting what looks to them like food for their young. We know by now that every second nature stresses a first nature, which, in effect, deteriorates; the victorious second nature then becomes the first. But are we ready for a plastic planet?

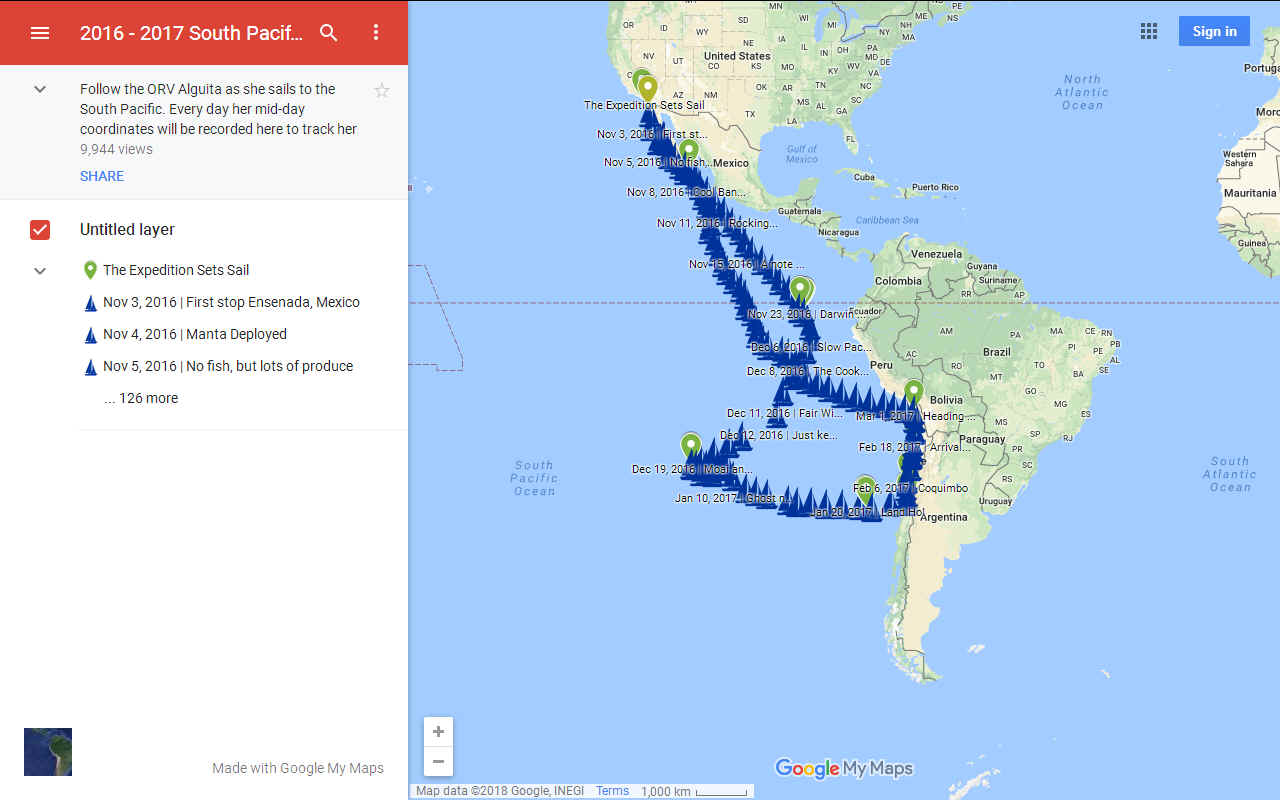

ALGALITA -

Founded by Capt. Charles Moore,

Algalita research maps the ocean for plastic concentrations.

This valuable data collection and recording is vital to know

what we are up against.

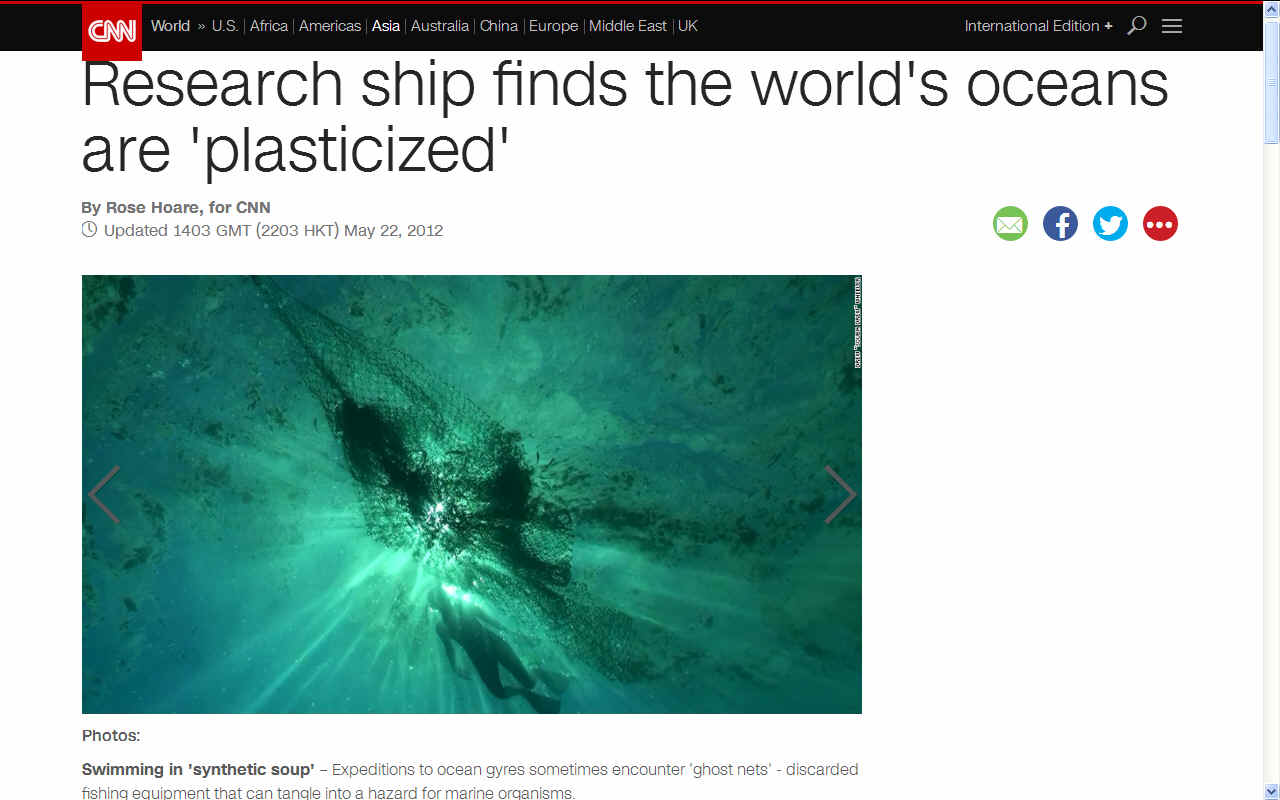

CNN 22 MAY 2012

A marine expedition of environmentalists has confirmed the bad news it feared - the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" extends even further than previously known.

Organized by two non-profit groups - the Algalita Marine Research Foundation and the

5 Gyres Institute - the expedition is sailing from the Marshall Islands to Japan through a "synthetic soup" of plastic in the North Pacific Ocean on a 72-feet yacht called the Sea Dragon, provided by

Pangaea Exploration.

The area is part of one of the ocean's five tropical gyres - regions where bodies of water converge, with currents delivering high concentrations of plastic debris. The Sea Dragon is visiting the previously unexplored western half of the North Pacific gyre - situated below the 35th parallel, and home to a massive expanse of plastic particles known as the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" - to look for plastic pollution and study its effect on marine life.

Leading the expedition is Marcus Eriksen, a former U.S. marine and Ph.D student from University of Southern California.

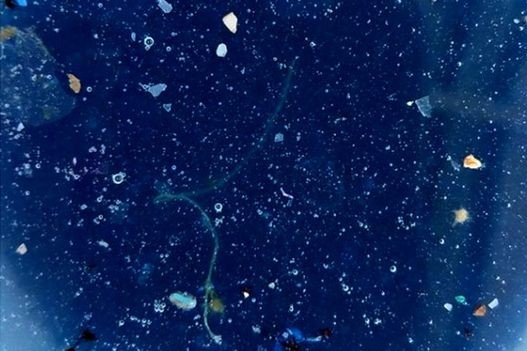

"We've been finding lots of micro plastics, all the size of a grain of rice or a small marble," Eriksen said via satellite phone. "We drag our nets and come up with a small handful, like confetti - 10, 20, 30 fragments at a time. That's how it's been, every trawl we've done for the last thousand miles."

Eriksen, who has sailed through all five gyres, said this confirmed for him "that the world's oceans are 'plasticized.' Everywhere you go in the ocean, you're going to find this plastic waste."

Besides documenting the existence of plastic pollution, the expedition intends to study how long it takes for communities of barnacles, crabs and molluscs to establish, whether the plastic can serve as a raft for species to cross continents, and the prevalence of chemical pollutants.

On a second leg from

Tokyo to Hawaii departing May 30, the team expect to encounter material dislodged by the Japanese tsunami.

"We'll be looking for debris that's sub-surface: overturned boats, refrigerators, things that wind is not affecting," Eriksen said. "We'll get an idea of how much is out there, what's going on and what it's carrying with it, in terms of toxins."

Scripps Institute graduate Miriam Goldstein was chief scientist on a similar expedition to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 2009. According to her research, there has been a 100-fold increase in plastic garbage in the last 40 years, most of it broken down into tiny crumbs to form a concentrated soup.

The particles are so small and profuse that they can't be dredged out. "You need a net with very fine mesh and then you're catching baby fish, baby squid

- everything," Goldstein says. "For every gram of plastic you're taking out, you probably take out more or less the equivalent of sea life."

Scientists are worried that the marine organisms that adapt to the plastic could displace existing species. Goldstein said this was a major concern, as organisms that grow on hard surfaces tend to monopolize already scarce food, to the detriment of other species.

"Things that can grow on the plastic are kind of weedy and low diversity - a parallel of the things that grow on the sides of docks," she says. "We don't necessarily want an ocean stuffed with barnacles."

Eriksen says the mood on the Sea Dragon has been upbeat, with crew members playing a ukulele and doing yoga, "but the sobering reality is that we're trawling through a synthetic soup."

Also on board is Valerie Lecoeur, founder of a company that makes eco-friendly baby and children's products, including biodegradable beach toys made from

corn, and Michael Brown from

Packaging

2.0, a packaging consultancy.

Eriksen says they have been discussing the concept of "extended producer responsibility".

"As the manufacturer of any good in the world today, you really can't make your product without a plan for its entire use, because you could eventually have 7 billion customers buy your product," he said.

"If one little button has no plan, the world now has a mountain of buttons to deal with. There is no room for waste, as a concept or a place

- there's just no place to put it anymore. That's the reality we need to face. We've got this plastic everywhere."

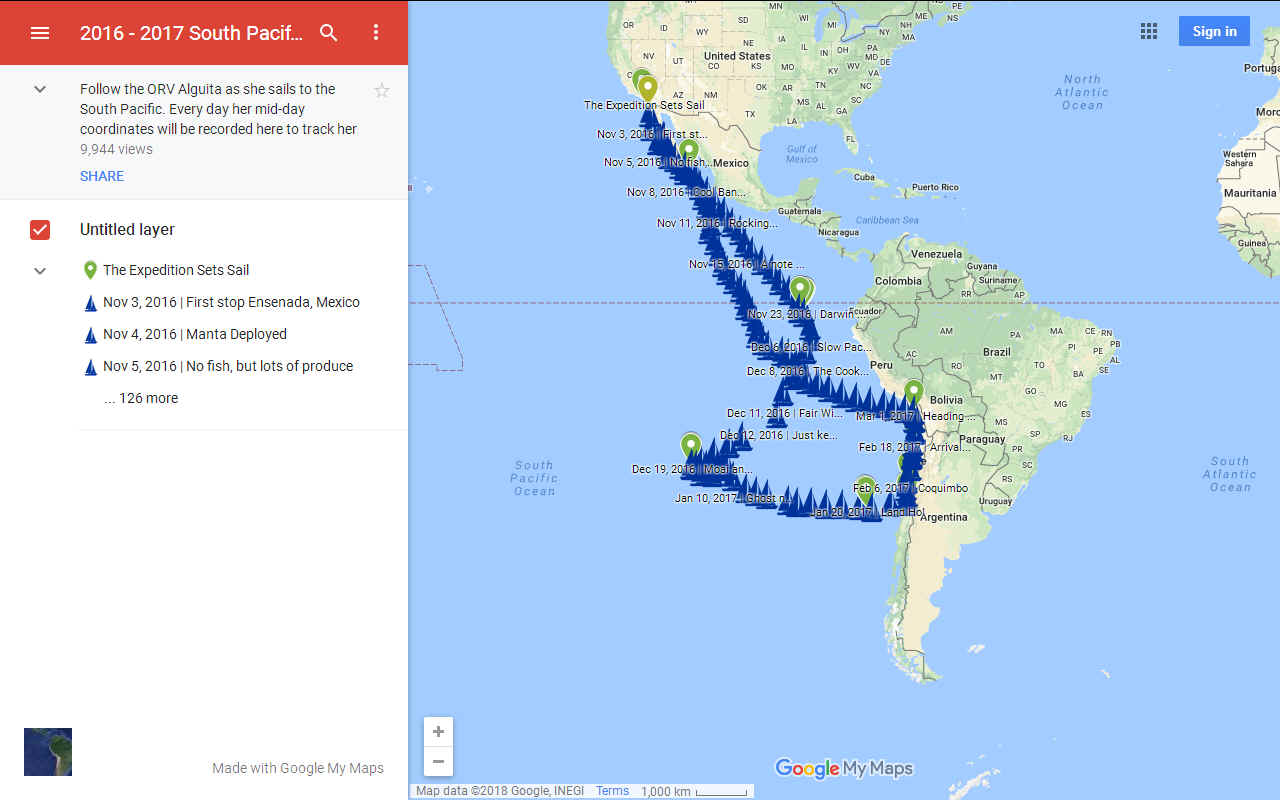

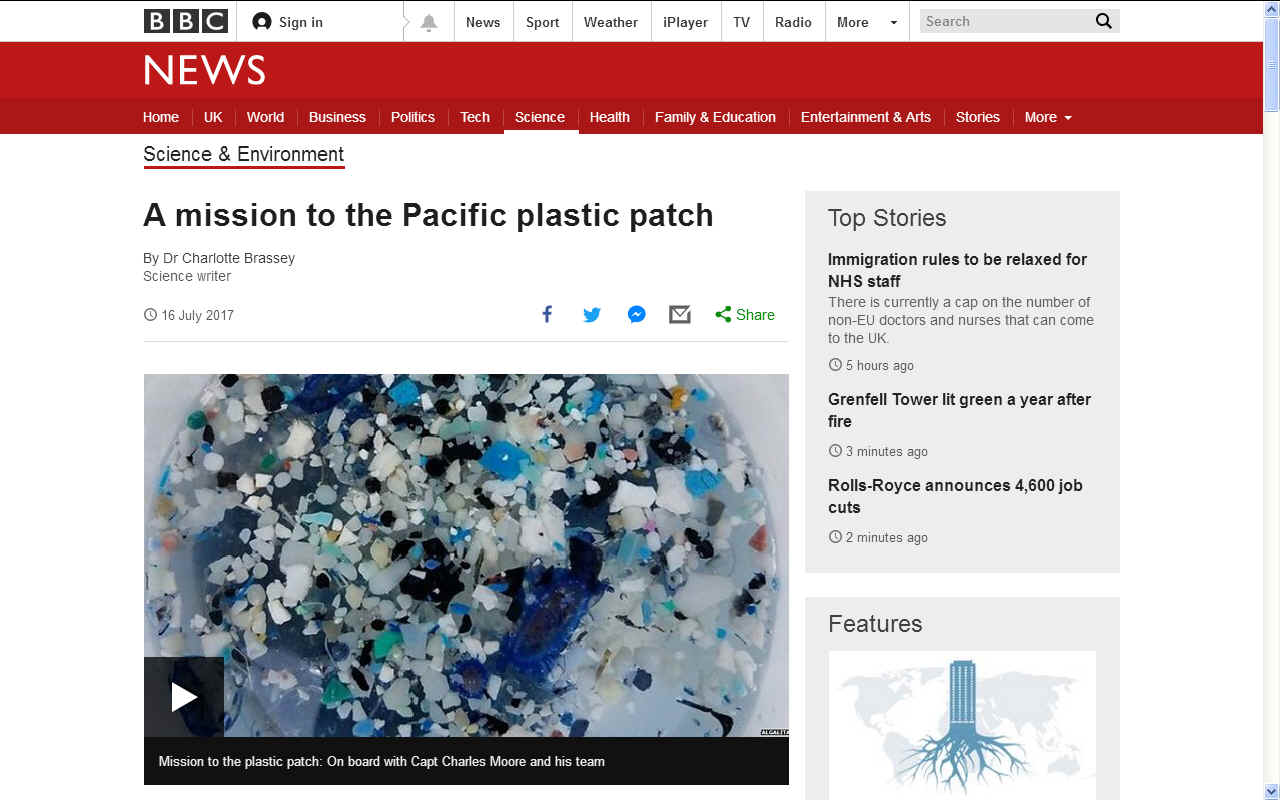

BBC NEWS 16 JULY 2017 - A mission to the Pacific plastic patch

A mariner who has spent years travelling "hundreds of thousands of nautical miles" to measure the impact of plastic waste in the ocean has estimated that a "raft" of plastic debris spanning more than 965,000 square miles (2.5m sq km) is concentrated in a region of the South Pacific.

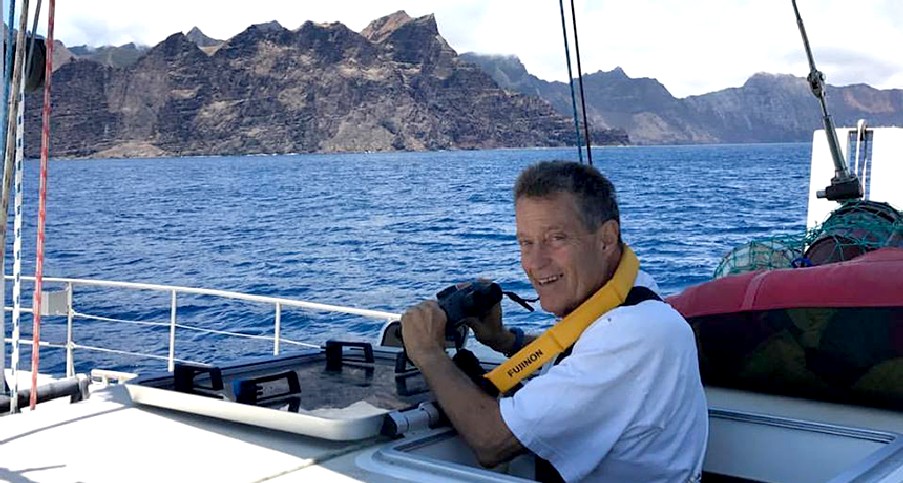

Capt Charles Moore has just returned from a sampling expedition around Easter Island and Robinson Crusoe Island.

He was part of the team which discovered the first ocean "garbage patch" in the North Pacific gyre in 1997 and has now turned his attention to the South Pacific.

Although plastic is known to occur in the Southern Hemisphere gyres, very few scientists have visited the region to collect samples.

Oceanographer Dr Erik van Sebille, from Utrecht University, says the work of Capt Moore and his colleagues will help fill "a massive knowledge gap" in our understanding of ocean plastics.

"Any data we can get our hands on is good data at this point," he told BBC News.

Capt Moore explained that the space occupied by sub-tropical gyres - areas of the ocean surrounded by circulating ocean currents - is approximately the same size as the entire land mass of the Earth, but they are now being "populated by our trash".

The phenomenon of oceanic garbage patches was originally documented in the North Pacific, but plastic has now been found in the South

Pacific,

Arctic and

Mediterranean.

"It's hard not to find plastic in the ocean any more," Dr van Sebille said. "That's quite shocking".

Capt Moore is the founder of Algalita Marine Research, a non-profit organisation aiming to combat the "plastic plague" of garbage floating in the world's oceans.

For more than 30 years, he has transported scientists to the centre of remote debris patches aboard his research ship, Alguita.

Dragging nets behind the vessel, the crew sieves particles of plastic from the ocean, which are then counted and fed into estimates of global microplastic distribution.

Although scientists agree that plastic pollution is a widespread problem, the exact distribution of these rafts of ocean garbage is still unclear.

"If we don't understand where the plastic is, then we don't really understand what harm it does and we can't really work on solving the problem," said Dr van Sebille.

YALE SCIENTIFIC

21 DECEMBER 2013

- MYTHBUSTER - From above the Pacific Ocean, all is calm. Blue water meets blue skies, each reflecting the other’s pure, infinite depths. But now a white scrap meanders by; not the reflection of a cloud, but a bobbing Styrofoam cup. Soon it is joined by two, now three, now ten, now fifty others, all jostling for space. They start to stack, forming hills, mountains. They support their plastic brethren: discarded bottles, packaging materials, webbed fishing nets. Worn-out tires pile atop one another forming rubber towers, while flimsy shopping bags flutter like flags in the breeze. It is an island of plastic the size of Texas, floating in the middle of the Pacific.

This is the image that comes to mind when people hear of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: a massive, floating heap of debris. However, while it is true that trash does find its way into the oceans, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not a floating island in the traditional sense. Instead, the Garbage Patch is composed of tiny plastic bits that linger unseen beneath the surface, ranging in size from a few square inches to barely visible specks.

Captain Charles Moore was the first to notice the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 1997. Then a racing boat captain, he was sailing from Hawaii to southern California when he stumbled upon “plastic […] as far as the eye could see.” In an article he wrote for Natural History, he described “plastic debris floating everywhere: bottles, bottle caps, wrappers, fragments.” Seeking to quantify the extent of the debris, he towed fine-mesh nets behind his boat, collecting the plastic bits along with plankton in the water. He found that the mass ratio of plastic to plankton was an astonishing 6:1.

Moore explained that the garbage patch was formed by a system of ocean currents. In large ocean basins between continents, currents tend to move in a circular pattern, known as a gyre. These wind-driven currents push water towards the center of the basin. This means that any pollution that enters the Pacific will eventually be pushed to the center of the gyre, where it begins to accumulate. Of course, the Pacific gyre is not the only ocean gyre — all of the world’s oceans have circular currents like these. This means that there is not just one garbage patch, but many; the two next-largest ones are found in the Northern Atlantic and the Indian Ocean.

While Moore’s description of ocean gyres holds true, his initial description of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has recently come into question. He claimed to “never [have] found a clear spot” in the ocean, perhaps leading to the hyperbolic tale of the floating island of garbage. In 2008, seeking to debunk the myth, Dr. Angelicque White of Oregon State University set off on a voyage through the heart of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. White’s team towed nets behind their boat, just as Moore had, but their data told a different story. Yes, tons of plastic were floating in the Pacific, but the vast majority of these plastic bits were tiny, with 90 percent of them spanning less than 10 millimeters in diameter. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, therefore, is less of an island and more a whirlpool filled with plastic confetti.

Despite the small size of the plastic bits, they can still have hugely negative impacts on the marine ecosystem. While larger plastics like six-pack rings can strangle marine animals, smaller plastics harm animals from the inside. The plastic waste is small and transparent, and it floats in the water column — just like plankton, which is a vital food source for fish and marine mammals alike. Animals cannot digest plastic, and if enough of it accumulates in their stomachs, they can die. Plastic can also contain toxins like DDT and PCBs. Once ingested, these chemicals do not break down, but build up in an organism’s body fat. As these organisms are consumed by larger and larger organisms, the levels of toxins increase dramatically, until those at the top of the food chain, including humans, are eating fish and fowl with dangerously high levels of toxins.

Although the myth of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch as a floating plastic island has been busted, the remaining facts are grim. Three ocean basins are rife with plastics, marine organisms consume plastic instead of plankton, and toxins climb up the food chain to humans. Is there a solution in sight? Scientists like Moore and White hope so. Researchers like them are currently working to understand the full scope of the garbage patches. Still, consumers should take note: it is only by drastically reducing plastic waste that the ocean gyres can hope to be cleaned for good. By choosing products wisely and recycling, consumers can take small steps to make the Great Pacific Garbage Patch into the Pacific that it should be: calm and quiet, where blue water meets blue skies.

By Taryn Laubenstein

Capt Moore and his crew hope to address this lack of data through their research trips.

On this latest voyage, Capt Moore and his colleagues are also investigating how plastic in the South Pacific Ocean may be threatening the survival of fish.

Lanternfish, that live in the deep ocean, are an important part of the diet of whales, squid and king penguins and the Algalita team says that plastic ingestion by lanternfish could have a domino effect on the rest of the food chain.

Christiana Boerger, a marine biologist in the US Navy, who has worked with the organisation, told BBC News that the problem of plastic consumption in fish can be "out of sight, out of mind".

She explained that "scientists need to actually travel to these accumulation zones" in order to bring the issue to the world's attention.

Ms Boerger has seen the impact of oceanic garbage patches first hand, aboard the Alugita and she says that some fish species "have more man-made plastic in their stomach than their natural food".

Globally, most of the plastic that ends up in the oceans comes from the land.

Litter is typically transported offshore by currents, which then form large revolving bodies of water, or gyres.

But Capt Moore says the South Pacific garbage patch is different from those in the Northern Hemisphere, because most of the litter appears to have come from the fishing industry.

Elsewhere, scientists are shifting their attention away from remote mid-ocean garbage patches to locations closer to home.

"If you think about plastic in terms of its impact, where does it harm marine life?" Dr van Sebille posed.

"Near coastlines is where biology suffers. It's also where the economy suffers the most."

Dr van Sebille also says that future research efforts need to focus on ecologically sensitive regions along the continental shelf. Even though the garbage patches cover a very large area "they are not that ecologically important", he said.

His team has previously studied the risk of plastics to marine animals, including turtles and sea birds. "Every time, we found that the risk is mostly outside of the garbage patches," he warned.

ORV

- stands for Oceanographic Research Vessel, and Alguita is the research vessel that has carried our research team to the most remote regions of the Pacific Ocean to study plastic pollution.

Most of the plastic pollution that they are finding in remote areas of the ocean found its way into the ocean through watersheds. Plastic litter on land flows directly out to sea when it rains.

In the future, Dr van Sebille hopes to understand more about how

plastic ends up on the coastline and is then subsequently transported to the oceans by storms. Interrupting this process might be an important mechanism for halting the growth of ocean garbage patches.

"A beach clean-up might turn out to be a very efficient way of cleaning up the ocean," he suggests.

In the meantime, humanity's love affair with plastic is unlikely to end soon. Plastic "will never be the enemy", concedes Capt Moore, "It has too many uses".

He explained that plastic pollution travels across national borders, so dealing with it required

international

collaboration.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://www.yalescientific.org/2013/12/mythbuster-the-truth-about-the-great-pacific-garbage-patch/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-40584629

http://www.packaging2.com/overview.php

http://5gyres.org/

http://www.panexplore.com/

https://edition.cnn.com/2012/05/21/world/asia/algalita-eco-solutions/index.html

https://www.algalita.org/

https://www.ted.com/speakers/charles_moore

SINGLE

USE PLASTICS - This is

just a small sample of the plastic packaging that you will

find in retails stores all over the world. A good proportion

of this packaging - around 8 millions tons a year, will end up

in our oceans, in the gut of the fish

we eat, in the stomachs

of seabirds and in the intestines of whales and other marine

mammals. Copyright photograph © 22-7-17 Cleaner

Ocean Foundation Ltd, all rights

reserved.

FOAM

& BOTTLES - Expanded polystyrene is

used to package household electrical goods, while soft drinks and water is

sold in PET plastic bottles by the billions every year. The numbers are

staggering. It's no wonder then that some of this plastic will end up on our

plate in one form or another, potentially as a toxin carrier. Copyright

photograph © 22-7-17 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd, all rights reserved. Animals do not recognize polystyrene foam as an artificial material and may even mistake it for food. Polystyrene foam blows in the wind and floats on water, due to its low specific gravity. It can have serious effects on the health of birds or marine animals that swallow significant quantities.

BIOMAGNIFICATION

- BP DEEPWATER - CANCER

- COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING NETS -

FUKUSHIMA - MARINE LITTER MICROBEADS

- MICRO

PLASTICS - OCEAN GYRES

- OCEAN WASTE -

PACKAGING - PCBS -

PET - PLASTIC

POLYSTYRENE

- POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS - SINGLE USE

- STRAWS - WATER

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2018. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital.

|