|

TUNA

ABOUT -

HOME - WHALING - A-Z INDEX

Anchovies

| Bass

| Bream

| Catfish

| Clams

| Cod

Coley

| Crabs

| Crayfish

| Eels

| Grouper

| Haddock

| Hake

| Halibut

| Herring

| Jellyfish

Krill

| Lobster

| Mackerel

| Marlin

| Monkfish

| Mullet

| Mussels

| Oysters

| Perch

| Piranha |

Plaice

| Pollock

| Prawns

| Rays

| Sablefish

| Salmon

Sardines

| Scallops

| Sharks

| Shrimp

| Skate

| Sole

| Sprat

| Squid

| Sturgeon

| Swordfish

| Trout

| Tuna

| Turbot

| Whiting

TUNA

CRISIS - They are taking out a generation of tuna': overfishing causes crisis in Philippines.

Men like Raul Gomez have been catching tuna for 40 years, but as fisheries in the region edge closer to collapse, he spends longer at sea to catch ever smaller tuna

In

an effort to feed a

growing population we should look at

alternatives lower down the food chain to increase the ratio

at which protein is harvested from the ocean, so bypassing the

conventional food chain where at each stage of consumption

there are significant losses in the conversion process. Jellyfish,

squid, krill

and filter feeders such a mussels could play a part in filling the widening gap between falling

fish stocks and higher demand to feed humans - so

relieving the pressure on tuna, salmon and other popular white

fish.

Humans

are the only species capable of changing their eating

patterns. Wild animals cannot. Ultimately then, humans

control the food supply for all life

on earth.

The

media regularly report on such matters thankfully, with The

Guardian being one of the most active news groups when it

comes to conservation issues.

THE

GUARDIAN 24

AUGUST 2018 - OVERFISHING CRISIS PHILIPPINES

Raul Gomez is an old man who fishes with five crew on a clipper in the seas known as the coral triangle, and he has spent two months now without taking enough to feed his family.

Riding out storms and searing heat in western Pacific waters, the burly, sun-inked Filipino uses a pole and line to reel in yellowfin tuna the size of an adult human.

This has been his trade for 40 years, but it is becoming tougher as fisheries in this region – one of the planet’s most important centres of tuna production – face the prospect of total collapse.

Gomez did not hear the dire prediction this year by the world’s leading body of biodiversity scientists, who warned that exploitable fish reserves in Asia-Pacific waters were on course to crash to zero by 2048.

All he knows is that with every year that passes, he has to spend ever longer at sea to catch ever smaller tuna, at greater personal risk and lower reward.

Gomez says that when he started out at the age of 14, he and his father would sail from General Santos port to the Sarangani Bay on a small bangka (outrigger boat). One night was enough to return the next day with 10 tuna, often weighing in at more than 100kg.

But the global surge in demand for sushi, sashimi and tinned tuna has brought more competition and massive overfishing.

Today, the bay is largely fished out, as are most of the surrounding waters in the Mindanao Sea, so he voyages further in clippers that can spend months away from port. But as the boats get bigger, the tuna are getting smaller. These days, Gomez considers himself fortunate to take a bigeye tuna of 70kg.

On his latest trip, his share of the take is just 4,000 pesos – equivalent to £1 for each of the 60 days he spent at sea.

“It is harder now to make a living and feed my family,” he says.

As soon as his boat docks, Gomez unloads his catch and then immediately prepares to set out again to make up for lost income. Once the hold is refilled with ice, he will be gone.

The fisherman sees his wife and children just two or three times a year even though they live less than half an hour from the port. His eldest son comes to spend a few hours with him on the foredeck, knowing his father could be away not just for months, but for years.

‘IT

IS TOTAL EXPLOITATION’

Gomez has been arrested and jailed three times for illegally fishing in

Indonesia, where the tuna are more abundant. His Filipino boss – the owner of the boat – orders him across the maritime border, but takes no responsibility when Gomez gets caught. Instead, the fisherman has to find his own way home.

“It’s a kind of slavery,” says Gomez (who asked that his name be changed due to concerns about retribution). “At times, I’ve gone years at sea for no pay.”

This is far from unusual. More than 600 Filipino fishermen have been jailed by Indonesia. Almost all were subcontracted by boat owners who gave no help in repatriating them.

“It is total exploitation. The fishers have no choice. They know that if they don’t cross the border they won’t have their contracts extended,” says Benjamin Sumog-oy of the Sentro labour organisation. “The relationship is feudal. The workers are not recognised as employees. They cannot join unions. They have no rights, no salaries. It is semi-slavery.”

Consumers in rich nations increasingly get their protein from seafood, but the rush to cash in has put pressure on fishing crews, driven down the quality of catches and eroded the sustainability of fisheries.

Several tuna species are in peril. Bluefin are critically endangered with just 2% of their 1950 biomass left, bigeye recently fell below the 20% level necessary for replacement, and yellowfin are also down more than 70%.

Major fishing nations such as Japan and South Korea have tightened restrictions in their coastal waters. But big companies increasingly use foreign-flagged ships and less-regulated overseas ports, particularly in the western and central Pacific.

World’s ‘tuna capital’

General Santos, which proclaims itself the “tuna capital”, is at the heart of this region, which is where one in every two of the world’s tuna is caught.

Tuna landings have steadily increased and there are plans to expand the port further by 2021. But many grumble that too much of the business is geared towards big – often foreign – vessels using purse-seine nets that land unsustainable catches of juvenile fish that would not be allowed in many other countries.

This leads to a rivalry inside the port, which cranks into life from 4am, when fishermen bring their catch to shore.

At Market One, pole-and-line fishermen like Gomez haul hefty adult fish over their shoulders along wooden planks to weighing machines, where they are hooked, measured and then carried to a bloodied table for butchering. At the highest end, traders email photographs of samples to buyers in Japan, South Korea, the US and Europe. The carcass is then packed with dry ice and sent to the nearby airport for freight via wholesalers to restaurants, sushi shops and supermarkets. Everything is done for a global market to global standards.

The story is very different at Market Two, which theoretically supplies domestic buyers. Bigger purse-seine ships dock here and discharge tonnes of smaller net-caught tuna on to a conveyer belt for sorting. Taking small, young fish would be prohibited in much of the world, but it is legal in the Philippines. While this may be necessary to feed a local population that has been largely priced out of the market for bigger fish, the bulk of this catch goes to canneries, which then sell to multinationals. A trader at Market One describes this as a form of tuna laundering.

A port regulator said warnings of fisheries disappearing before 2050 are realistic and terrifying.

“There are more fishers and less fish. That’s the problem,” said the official. “There will have to be restrictions in the future.”

Four years ago, the Philippines was given a yellow card over its fisheries by the

European

Union, prompting the government to pass a stricter fishing law. But there is still no harvesting strategy and illegal and unregulated fishing remains commonplace.

During the Guardian’s visit, young yellowfin and big-eye – none more than 50cm long – were seen on the conveyor belt from ships into General Santos market.

“There is a lot of illegal fishing in General Santos,” says Vince Cinches, Philippines oceans campaigner for Greenpeace south-east Asia. “They are taking out a generation of tuna.”

Harvest limits, better monitoring and traceability – not to mention unionisation – could also help fishers such as Gomez, who feels the pressure of declining stocks and rising demand more than anyone.

For now though, what the old salt catches he cannot afford to eat; what he earns is no longer enough for his family. His wife is now the main breadwinner and the main dish on the dinner table is ever more likely to be chicken than tuna.

JAPANESE

OVERFISHING 2017

- Japan is set to exceed bluefin tuna quota amid warnings of commercial extinction.

Conservationists call on Japan to abide by fishing agreements after reports annual quota will be exceeded two months

early.

THE

GUARDIAN 24 APRIL 2017 - JAPAN EXCEEDS BLUE FIN TUNA

QUOTA

..Conservation groups have called on Japan to abide by international agreements to curb catches of Pacific bluefin tuna after reports said the country was poised to exceed an annual quota two months early – adding to pressure on stocks that have already reached dangerously low levels.

Japan, by far the world’s biggest consumer of Pacific bluefin, has caused “great frustration” with its failure to abide by catch quotas intended to save the species from commercial extinction, said Amanda Nickson, the director of global tuna conservation at Pew Charitable Trusts.

“Just a few years of overfishing will leave Pacific bluefin tuna vulnerable to devastating population reductions,” Nickson said in Tokyo on Monday. “That will threaten not just the fish but also the fishermen who depend on them.”

Decades of overfishing have left the Pacific bluefin population at just 2.6% of its historical high, and campaigners say Japan must take the lead at a summit in South Korea this summer.

In 2015, Japan and other members of the Western & Central Pacific Fisheries Commission agreed to curtail catches of immature bluefin, halving the catch of fish under 30kg from the average caught between 2002 and 2004.

But Japanese media reported last week that the country would reach its catch limit for younger tuna for the year through to June two months early.

Some fisheries workers have ignored the restrictions, aware that they will not be punished and can fetch premium prices for Pacific bluefin in Japan, where it is regarded as an important part of the country’s culinary heritage.

Campaigners support the fisheries commission’s aim of rebuilding stocks to at least 20% of unfished levels by 2034 – a target Nickson said was “realistic and attainable”. She said further inaction could revive calls for a two-year commercial moratorium on catching Pacific bluefin.

“No country in the world cares more about the future of tuna than Japan,” she said. “Japan can take the lead, but it must start by committing itself to the 20% rebuilding plan.”

If that fails, she added, “then a full commercial moratorium could be the only feasible course of action”.

Aiko Yamauchi, the leader of the oceans and seafood group for WWF

Japan, said it was time to penalise fishermen who violated catch quotas. “The quotas should be mandatory, not voluntary,” Yamauchi said. “That’s why the current agreement hasn’t worked.”

About 80% of the global bluefin catch is consumed in Japan, where it is served raw as sashimi and sushi. A piece of otoro – a fatty cut from the fish’s underbelly – can cost several thousand yen at high-end restaurants in Tokyo.

TUNA

MAY 2016

- Overfishing puts $42bn tuna industry at risk of collapse. Experts make first estimate of the value of tuna fisheries and warn Pacific Islanders have most to lose from declining stocks.

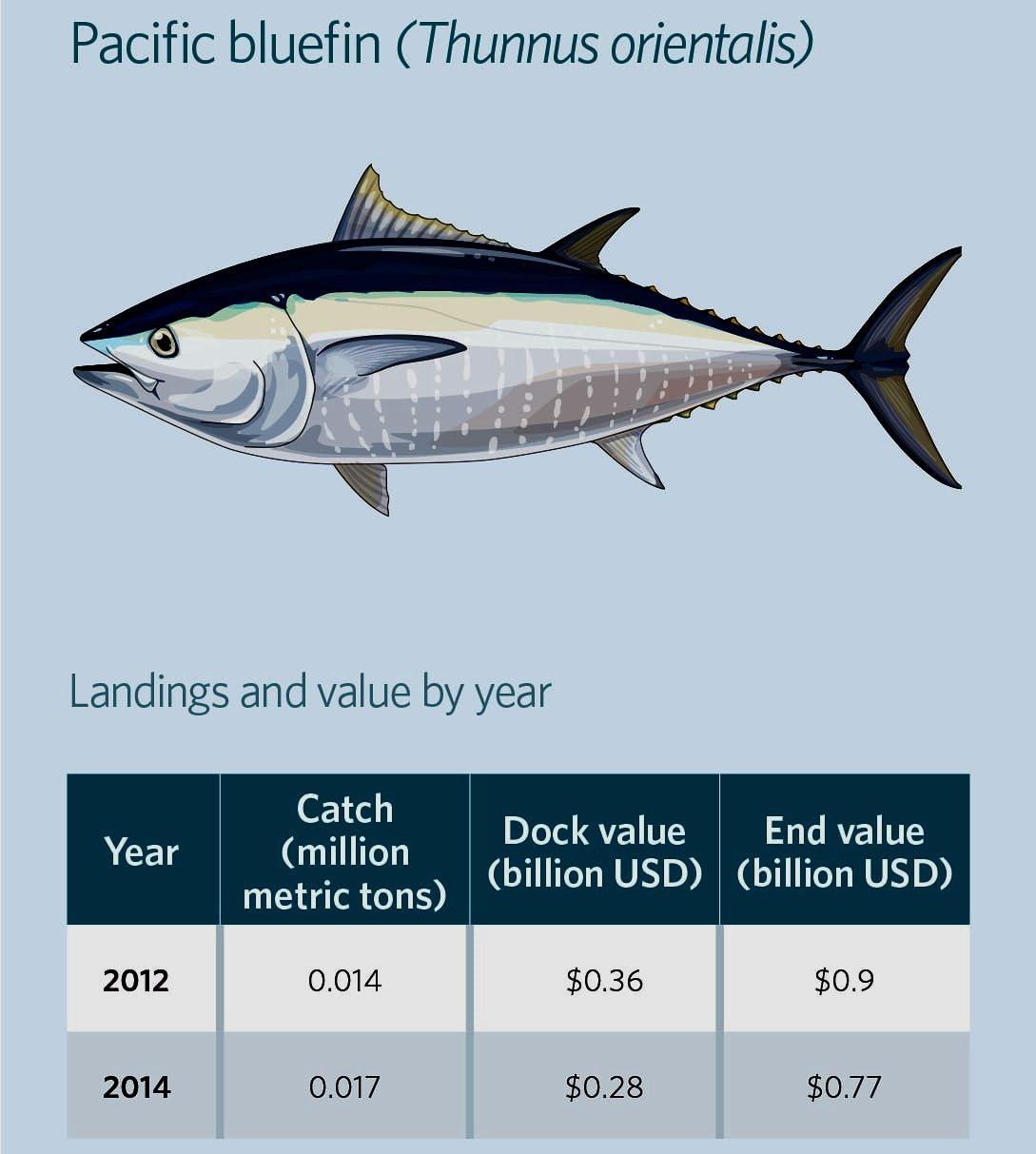

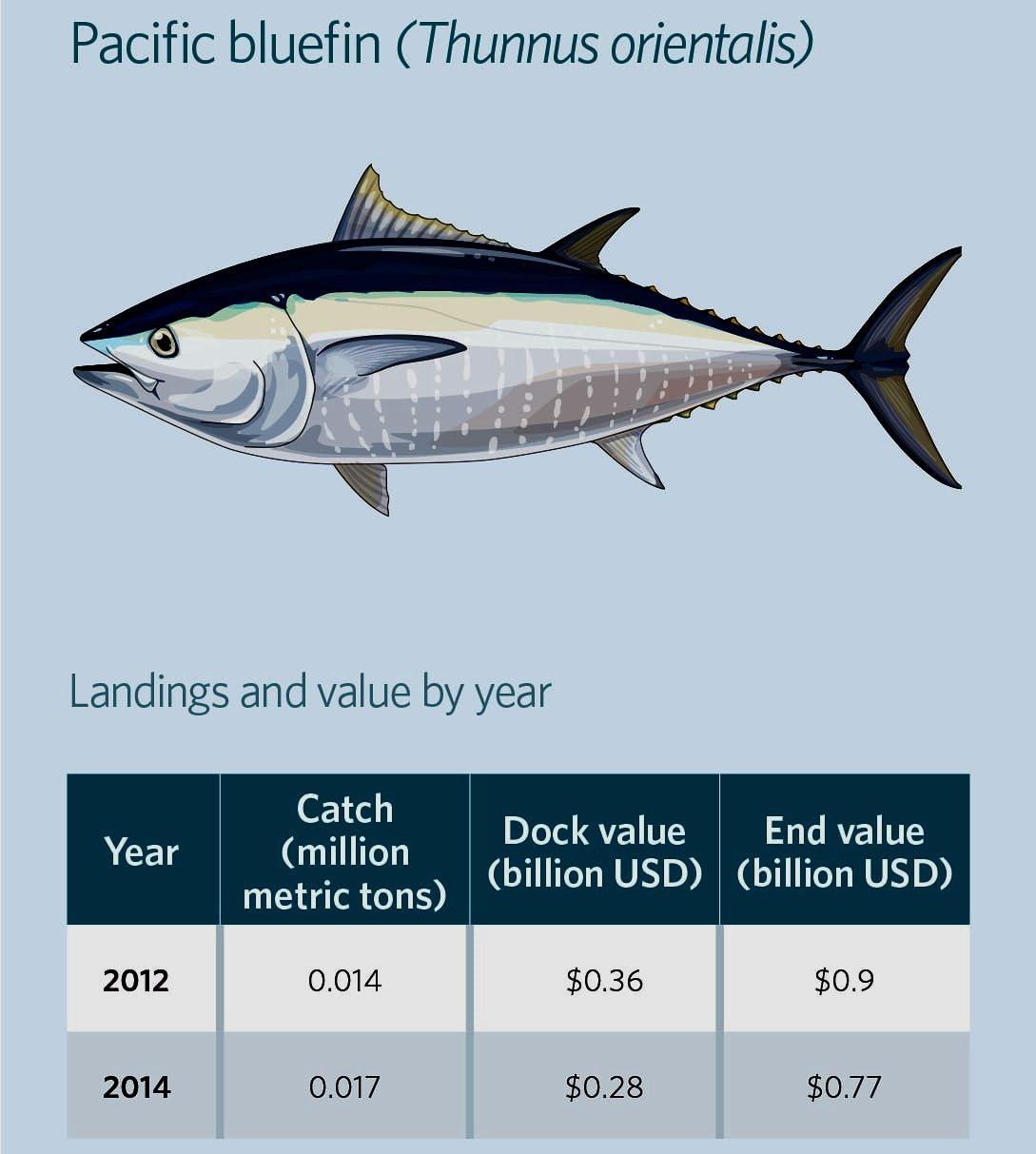

The seven most commercially important tuna species have an end value of more than $40bn, according to a

Pew report.

THE

GUARDIAN MAY 2016

Overfishing is jeopardising a global tuna industry worth more than $42bn (£29bn), according to the first assessment of its kind. A report produced by the Pew Charitable Trusts has highlighted the significant revenues that fishermen, processors and retailers are generating from severely depleted species of tuna.

Taken together, the seven most commercially important tuna species – skipjack, albacore, bigeye, yellowfin, atlantic bluefin, Pacific bluefin and southern bluefin – generated $12bn (£8bn) for fishermen in 2014, while the full value, including the total amount paid by the final consumer at supermarkets and restaurants around the world, was estimated to be $42bn (£29bn).

“It’s no secret that tuna are big business,” said Amanda Nickson, Pew’s director of global tuna conservation. “Now, for the first time, we’re able to put an actual price on what’s at stake in the fight for the conservation and sustainable management of these commercially and ecologically important

fish.”

The report also highlights how tuna is a vital source of revenue to fishing communities, particularly Pacific Islands. The total catch in the Pacific Ocean was estimated at $22bn in 2014.

Pew says that income will be at risk unless companies and governments, particularly Japan, US and those in the EU, can agree to catch limits that allow stocks to recover. Five out of the eight tuna species are at risk of extinction due to

overfishing, according to conservationists.

“The tussle at the moment is a lot to do with the fact that as the less affluent players, particularly the islands in the Pacific, realise the value of the resource they have, they will want to take a stake in that. And those who have historically fished it do not necessarily want to give that stake away.

“We don’t want to see tuna stocks depleting because the countries involved can’t agree sensibly on the management of them,” said Nickson, who called for scientifically-informed catch limits to enable heavily depleted stocks, such as Pacific bluefin tuna, to recover and prevent others such as skipjack becoming overfished.

Most of the tuna industry is currently paying “lip service” to efforts to better manage tuna stocks, said Nickson, but she praised the steps being taken by some UK retailers and processors.

Tesco,

Sainsbury’s,

Asda,

M&S,

Morrisons and

Co-op recently backed a call to cut yellowfin tuna catches in the Indian Ocean in an effort to help stocks recover.

“You’ve got two ways that we are going to see change in the supply chain,” said Nickson. “Either a regulatory process saying you can only catch this much, forcing the industry to adjust to that, or you are going to see market pressure from retailers saying we don’t want to purchase from any place that can’t actually demonstrate specific sustainability steps. Consumers should be able to buy tuna and not have to worry about where it is from. It is up to retailers and processors to better manage stocks.”

Much of the concern from conservation experts in recent years has centred on bluefin tuna stocks. Although not yet classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as endangered (it is listed as vulnerable), Pacific bluefin tuna has seen stocks depleted to less than 3% of its historic levels. It was just under 4% in 2012.

The report estimated that the 17,000 metric tonnes of pacific bluefin caught in 2014 had a final value of $770m. In comparison, the 2.8m metric tonnes of skipjack caught in 2014, not currently overfished and most often used for canned

tuna, had an end final value of $17.7bn.

By Tom

Levitt

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/09/one-in-three-fish-caught-never-makes-it-to-the-plate-un-report

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/may/02/overfishing-42bn-tuna-industry-risk-collapse

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/aug/23/they-are-taking-out-a-generation-of-tuna-overfishing-causes-crisis-in-philippines

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/may/02/overfishing-42bn-tuna-industry-risk-collapse

MARINE

LIFE - This humpback

whale is one example of a magnificent

animal that is at the mercy of human

activity. Humans are for the most part unaware of the harm their fast-lane

lifestyles are causing. We aim to change that by doing all we

can to promote ocean

literacy.

Anchovies

| Bass

| Bream

| Catfish

| Clams

| Cod

Coley

| Crabs

| Crayfish

| Eels

| Grouper

| Haddock

| Hake

| Halibut

| Herring

| Jellyfish

Krill

| Lobster

| Mackerel

| Marlin

| Monkfish

| Mullet

| Mussels

| Oysters

| Perch

| Piranha |

Plaice

| Pollock

| Prawns

| Rays

| Sablefish

| Salmon

Sardines

| Scallops

| Sharks

| Shrimp

| Skate

| Sole

| Sprat

| Squid

| Sturgeon

| Swordfish

| Trout

| Tuna

| Turbot

| Whiting

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. Copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2022. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital.

|