|

F

I S H E R I E S

ABOUT - CLIMATE -

FOUNDATION -

HYDROGEN -

OCEAN PLASTIC

- WHALING

PLEASE

USE OUR

A-Z INDEX

TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE WHERE PAGE LINKS MAY LEAD TO EXTERNAL

SITES,

OR RETURN HOME

ALL

FISHED OUT - A recent United Nations study reported that more than two-thirds of the world's fisheries have collapsed or are currently being

over fished. Much of the remaining one third is in a state of decline due to habitat degradation from pollution and climate change.

Escalating amounts of point and non-point pollution continue to threaten water quality and fish habitat.

Yet, the human population consumes over 100 million metric tons of fish

annually and more than 25% of the world’s dietary protein is provided by

fish.

In 2015, the EU supply (domestic production + import) slightly decreased by 381.872 tonnes compared to 2014, moving from 14,94 to 14,56 million tonnes. The main driver was domestic production from fishing which declined by 299.699 tonnes.

Household expenditure for fisheries and aquaculture products in the EU reached its peak in 2016, at EUR 54,8 billion. Compared to 2015, consumers in all EU Member States, except the UK and Poland, spent more money on seafood in 2016. Per capita expenditure in Portugal was again the highest at EUR 327.

Over the last 8 years, price inflation for fish in the EU has been higher than for food in general, especially in the northern countries. From 2015 to 2016, inflation for fish was 3%, while no increase in prices was observed for food in general. In the first five months of 2017, prices of fish have remained stable. Compared with the same period last year, they were up by almost 4%.

The

Food

and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that fish represented one-sixth of animal protein supply and 6.5% of all protein for human consumption; and 20% of animal protein intake comes from fish for 3.2 billion of the

world’s

population. Biomass is derived from capture fisheries and wild harvesting and from

aquaculture and mariculture.

16M

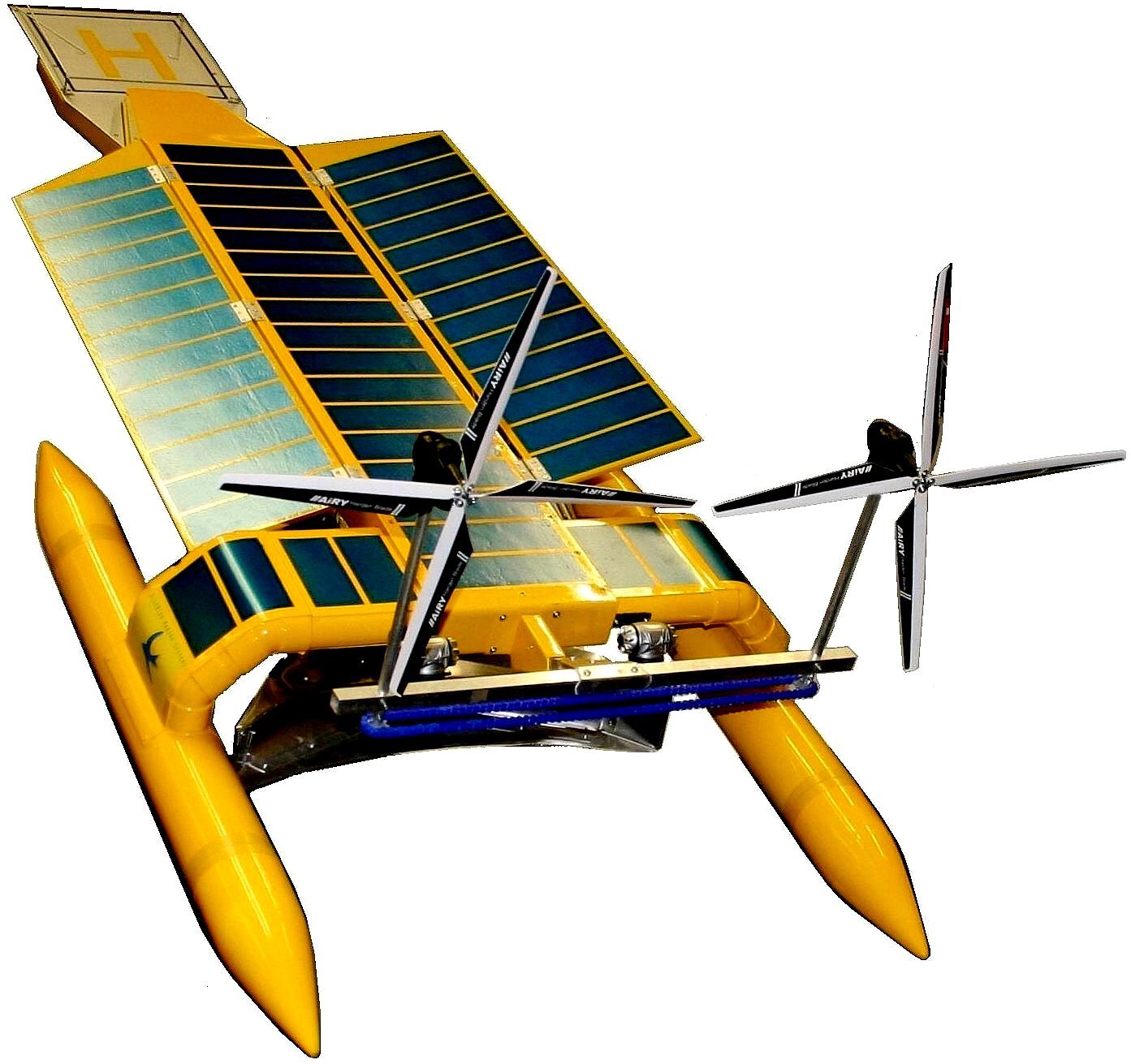

ZERO CARBON FISHING VESSELS - This is a proposal for a 20 ton fishing

vessel derived from the SeaVax

concept that uses no plastic

nets and is powered by the wind and sun. The wind

generators and solar arrays are shown safely folded and locked

for docking in harbour. Copyright ©

diagrams October 24 2019. All rights reserved, Cleaner Ocean

Foundation Ltd and Bluebird Marine Systems

Ltd.

Food or human nutritional uses of marine and aquaculture biomass include:

• Direct-to-consumer via artisan fishing, markets, retail sale and restaurants;

• Fillets and other primary-processed material such as roes, ex-shell molluscs and crustacea;

• Fish oils for nutritional supplements and omega-3 fatty acids;

• Fishmeal extracts for protein and oils for human nutrition;

Chopping/mincing of edible trimmings for processed fish products such as surimi and prepared frozen or chilled foods;

• Seaweed hydrocolloids for food and pharmaceutical use;

• Seaweed extracts for nutritional supplements and anti-oxidants;

• Whole and extracted microalgae for nutritional supplements, antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids;

• Higher-value elements: collagens, gelatins, minerals, chitin derivatives, carotenoids, enzymes, amino-acids, for nutrition and supplementation.

Non-food uses or treatments of marine and aquaculture biomass include:

• Higher-value elements: collagens, gelatins, minerals, chitin derivatives, carotenoids, enzymes, amino-acids, peptones, for animal nutrition, laboratory, chemical, agricultural uses – the same potential as for materials of food-grade quality, but essentially manufactured from biomass not of food grade;

• Fishmeal and fish oil for animal feed;

• Minced fish for petfoods;

• Fishmeal extracts for petfoods;

• Ensiling for protein concentrates and hydrolysates for animal nutrition;

• Processed fish oils for industrial uses;

• Chopping/mincing/freezing for direct baits, animal and fish feeds;

• Composting for fertiliser/soil improver;

• Aerobic Digestion for biogas and fertiliser/soil improver;

• At-sea discards (e.g. pollock RRM by Russian fisheries, and bycatch);

• Landfill (less so in Europe and other developed states).

NEW

YORK TIMES - NOV 30

2017: While Russia, the United States and three other countries with Arctic coastline control the exclusive economic zones near their shores, overfishing in the international waters at the central Arctic Ocean could collapse fish stocks.

Whatever their disagreements elsewhere, the countries have a shared interest in protecting the high Arctic from such unregulated fishing, which could affect coastal stocks as well, conservationists say.

To address the problem, five nations with Arctic shorelines completed negotiations on Thursday with countries farther south that operate major trawling fleets. The agreement imposes a moratorium on fishing in newly ice-free areas in the high Arctic, at least until scientists can study the ecology of the quickly thawing ocean.

The agreement was a step forward for conservation in the Arctic, and was reached despite tensions between the United States and Russia that had delayed an earlier, more limited moratorium, and in spite of President Trump’s skepticism about global warming. Mr. Trump has said he intends to work with Russia to solve common problems.

The deal prohibits trawling in the international zone of the Arctic Ocean that is newly free of ice for 16 years, or until a plan for sustainable fishing is in place.

To take effect, the agreement on a high-latitude fishing ban must be signed by all the countries involved: the United States, Norway, Denmark, Canada and Russia, which all have Arctic shorelines; and South Korea, China, Japan, the European Union and Iceland, which operate ocean trawling fleets.

The coastline states had already agreed in 2015 to a voluntary moratorium on trawling in Arctic waters. But the agreement had little meaning if nations to the south did not also join in.

That the center of the Arctic Ocean was unregulated was hardly a concern when it was an icebound backwater. That is changing. Today, about 40 percent of the central Arctic Ocean melts in the summertime. Though nobody fishes there now, the ice-free water could have lured in industrial fleets.

“This is a landmark agreement,” said David A. Balton, the deputy assistant secretary for oceans and fisheries at the State Department, who negotiated the agreement for the United States. “It’s a rare case of governments doing something in advance, to prevent a problem from arising.”

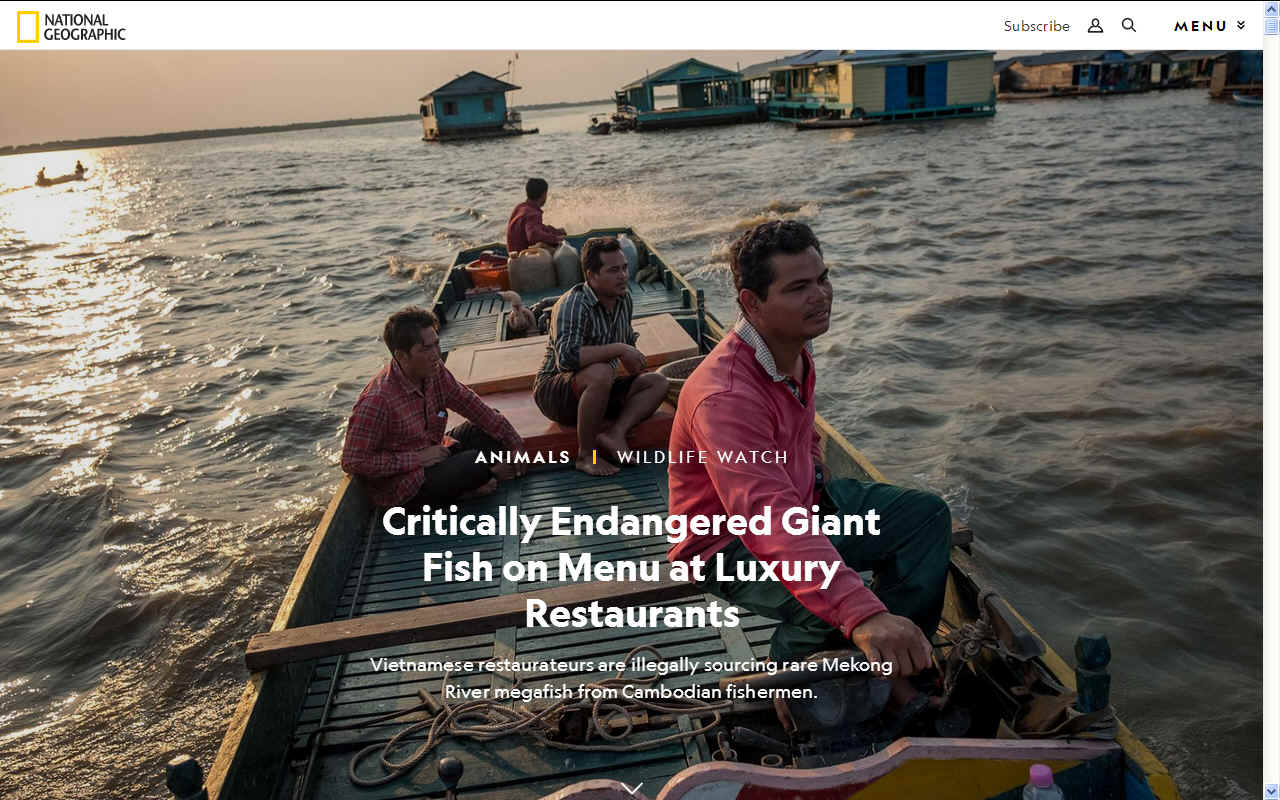

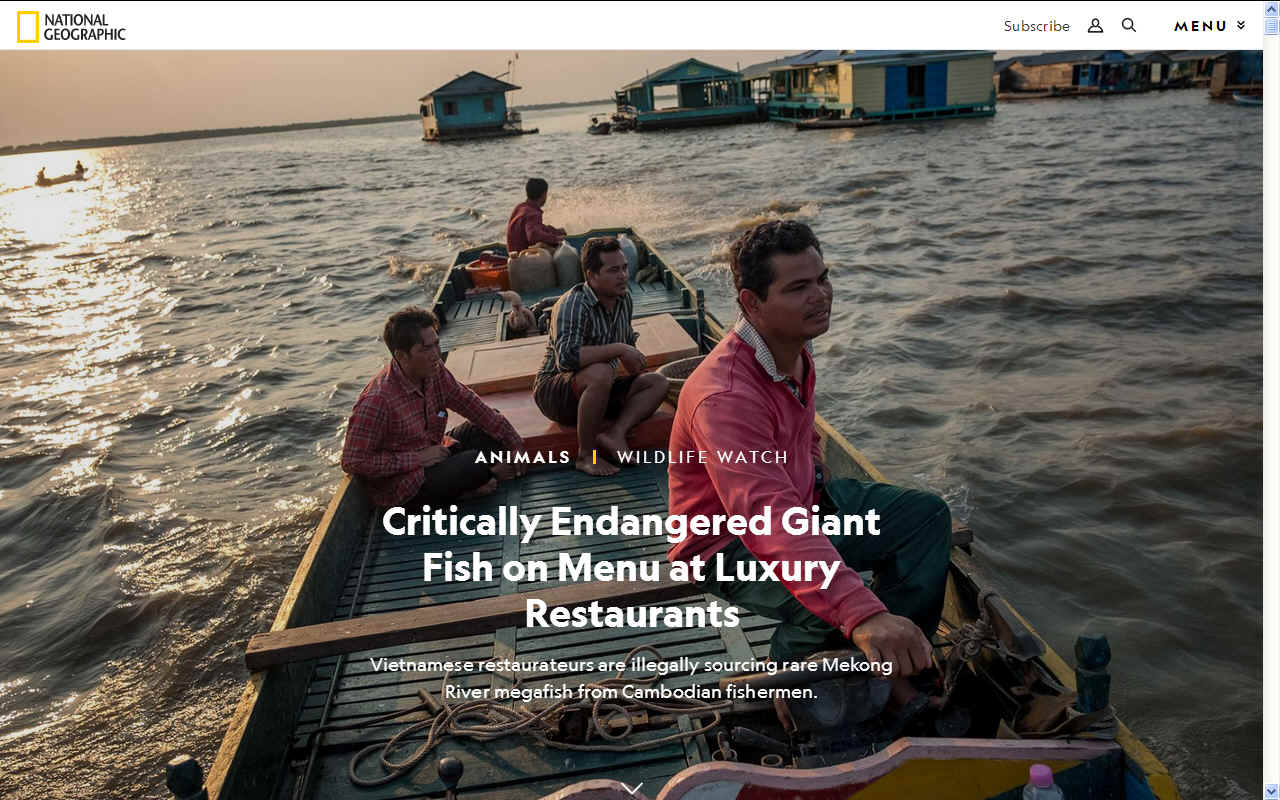

NATIONAL

GEOGRAPHIC JULY 2018 - From the outside Nha Hang Lang Nghe, in Danang, looks like any other respectable restaurant in Vietnam. Tables are invitingly laid out in the shade of a lush garden, and festive traditional art lines attractive brick walls. Families laugh over hot pots, and businessmen clink glasses.

Yet the veneer of wholesome normality masks a dark truth: Critically endangered giant river fish are Lang Nghe’s signature dish. Although it’s illegal to sell them in Vietnam, signs at the entryway entice diners with photos of imperiled Mekong giant catfish (“tasty meat, rich in omega-3”) and giant barbs (“good for men”), while a video showing a 436-pound giant catfish being cooked and eaten plays on a screen inside. Advertisements on social media likewise boast of the delightful flavor of the enormous fish, and of their rarity.

Lang Nghe is part of a growing trend of restaurants across Vietnam that are aggressively cultivating a new, dangerous market for megafish. The species they offer are so rare that the removal of even a few individuals—up to six a month in the case of Lang Nghe—may tip the animals toward extinction. But because wild freshwater fish don’t attract the same attention as tigers, elephants, rhinos, or pangolins, very few people know they’re being targeted—and even fewer are doing anything to stop it.

“The new trade seems to be very pervasive and growing very rapidly,” said Zeb Hogan, a National Geographic explorer and biologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, who’s an expert on the giant fish of the Mekong River system. “It needs to be dealt with if these species are going to survive.”

Hogan first learned that the species he studies—mainly the Mekong giant catfish and the giant barb—are being eaten in Vietnam when someone sent him a link to a restaurant’s Facebook post about a year ago. He quickly uncovered dozens of similar ads and related Vietnamese media stories. “Seeing pictures of the fish, I didn’t think the largest and most endangered ones could be coming from the aquaculture industry,” he said. “They were much too big. It looked like they must be coming from the wild.”

Although restaurant staff and media stories sometimes say the giant fish come from Thailand and Laos, the bulk of them seem to originate in Cambodia.

Trading Mekong giant catfish and giant barbs violates both international and domestic law in Cambodia. That’s also the case in Vietnam, where several species of megafish, including giant catfish and giant barbs, have been protected since 2008. While Cambodia’s current penal code doesn’t specify a punishment for poaching protected fish, in Vietnam maximum penalties for exploiting those species can result in fines of $88,000 for individuals or $658,000 for businesses, and 15 years in jail. Yet enforcement is weak: No documented evidence exists of any giant fish having been so much as seized from Vietnamese restaurants openly selling them.

Alarmed by the trend, Hogan got in touch with illegal wildlife trade researchers and activists in the region. But no one seemed to have any idea what he was talking about. All were focused on terrestrial or marine species. “Freshwater fish aren’t a priority in wildlife conservation circles,” Hogan said. “They’re hard to study, not much is known about them, and there’s not as much public empathy and support.”

Hogan is a scientist, not a wildlife trade investigator, but in January 2018 he and National Geographic set out to search for answers to basic questions about the trade: Why are these fish now appearing in restaurants in Vietnam? Where are they coming from? Finding that out is a crucial piece of the puzzle for stopping the trade.

Monsters have long lived in the Mekong, one of the world’s most biodiverse rivers. Starting in the Tibetan Plateau and meandering through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, its 2,600-mile-long, latte-brown vein conceals a fantastical array of nearly a thousand fishes, many found nowhere else. Thanks to the river’s enormity and productivity, about a dozen of them grow to record proportions.

“These are some of the largest, most extraordinary, and iconic fish in the world,” Hogan said. “They’re big enough to strike even the most experienced fishermen with awe.”

There’s the 500-pound giant freshwater stingray—a brown behemoth that glides through the water like a flying saucer—along with the giant devil catfish, a predatory species that looks like a mix between a shark and an alligator. There’s the giant salmon carp, whose perpetually downturned mouth would give Grumpy Cat a run for her money. And the giant barb, a blimp with thick, blubbery lips and scales the size of your palm, sometimes referred to as the 600-pound goldfish. Best known of all, though, is the Mekong giant catfish. Growing up to 10 feet long and 650 pounds, it’s regarded throughout the region as the king of fish.

More than just throwbacks to a wilder, more awe-inspiring time, the giants—as the rarest of the rare—in Cambodia and Laos indicate by their presence that the Mekong River ecosystem, while overfished and degraded in parts, is still functioning well enough to sustain all those less threatened species as well. Protecting the giants means protecting a living Mekong, and everything in it.

Hogan has been studying Southeast Asia’s endangered giant fish since 1997. Because giant catfish and giant barbs are so elusive, in 2000 he began networking with local fishermen and encouraging them to call his partners at Cambodia’s Fisheries Administration whenever they unintentionally caught a giant fish. The researchers would then rush to the scene to measure the fish, tag it, and release it, and the fisherman would get a small payment (not to mention bragging rights) for helping.

For years the system worked well: The fish hot line received up to 10 calls a year, and tagged fish began turning up in locations hundreds of miles apart, allowing Hogan and his colleagues to track their movement and growth. But during the past five years or so, the calls have diminished to just one or two a year—or sometimes none at all.

SCARCITY FUELS DEMAND - In Vietnam’s stretch of the Mekong, giant fish were imperiled well before Vietnamese restaurant owners sniffed them out, thanks to a mix of overfishing, pollution, and building of dams, which block essential migratory routes and change the river’s natural dynamics. There, the creatures now seem to be little more than the ghosts of old-timers’ monster tales.

“Even though the International Union for Conservation of Nature says we should protect giant catfish and giant barbs, every time people caught them in Vietnam, they were eaten,” said Mai Dinh Yen, a retired ichthyologist from Hanoi National University. “There has never been a case in which these fish were caught and then released back into the river.”

Yet it’s precisely the fact that the fish are almost gone that certain diners covet. In Vietnam, to be able to obtain and afford something scarce—even if, and sometimes especially if, it’s against the law—is a mark of one’s importance, wealth, and power. This mind-set is a major influence behind the sale of illicit wildlife goods like pangolin meat, rhino horn, ivory, and tiger parts, and it seems to be playing a role in the trade of megafish too. Their flesh has been described in the Vietnamese media as having the ability to bring good luck and boost sexual performance.

“Vietnamese people have a saying that the bigger the fish is, the better it tastes,” said Hoang Trong Nghia, manager of Nha Hang Ngu Quan, a restaurant in Hanoi that specializes in the giants. He texts a growing pool of regulars every time one arrives. “Some people even buy giant fish as a gift for a business colleague or for a big family party because it’s so rare,” he explained. “It’s not a common gift, so it’s more special.”

Prices vary by species and size, Nghia said, with giant barbs weighing more than 220 pounds fetching the most—about $80 a pound. “Giant barb is the most expensive because it’s so rare and the quality is so great. Sometimes we even have to bid with other restaurants for it.” The largest fish he ever received, however, was a Mekong giant catfish, caught in Cambodia in December 2016 and weighing 617 pounds. “It looked like a buffalo,” Nghia said.

Fish like that can’t be ordered in advance because they’re so rare, he added—and they must be caught in the wild. This isn’t just a practical consideration: Wildness, like rarity, is a highly valued attribute in Vietnam.

All four restaurants I visited in the country assured me that their giant fish come from the wild. But when I spoke on the phone with Ly Nhat Hieu—who owns Hang Duong Quan, a multibranch Ho Chi Minh City restaurant that specializes in “terrible fish” and boasts a celebrity and VIP clientele—he denied that claim. “I just buy the fish from the market,” he said. “There are many, many fish farms in Vietnam now where people can grow these fish. It’s nothing special, and it’s not the natural fish.”

This runs counter to what’s reported in media stories about Hieu’s restaurant, even including posts on his restaurant’s own website, all of which state that Hang Duong Quan’s fish come from the wild—and his restaurant staff say so too. “The owner even has relatives in Cambodia to find and source the fish for him,” said a waiter at the restaurant, whom National Geographic is not naming to protect his job. “He has a lot of connections in that area, so we have giant fish all the time.” Hang Duong Quan’s largest fish, imported in late 2017, was a 6.5-foot-long, 550-pound giant catfish—a fish, according to the waiter, that “can only live in the Mekong River in Cambodia.”

Thomas Raynaud, aquaculture director at Neovia Vietnam, a French company specializing in livestock and aquaculture management and health, agreed that such a massive fish almost certainly comes from the wild. Mekong giant catfish aren’t farmed in Vietnam, he said, and while there is some farming of giant barbs, their maximum weight seldom exceeds 20 pounds, and production is very low. Farming these species to gigantic proportions would take many years of effort and “is not realistic,” Raynaud said.

Nor are aquaculture-grown giants likely to be imported from other countries. Thailand has a number of well-established Mekong giant catfish farms, but those fish normally weigh no more than about a hundred pounds when sold.

“I’ve never heard of a pond that raised Mekong giant catfish that can grow to 300 pounds or more,” said Naruepon Sukumasavin, director of the administrative division of the Mekong River Commission in Vientiane, the capital of Laos. Some Mekong giant catfish, he added, do grow to nearly 450 pounds in government-stocked reservoirs in Thailand, but he knows of no such operations in Cambodia, Vietnam, or Laos.

Giant barbs, on the other hand, are a completely different story, Sukumasavin said. Though the species has been bred in captivity for more than 40 years, those fish are almost always released into the wild—not sold for meat.

Total global wild catches have remained relatively unchanged for the past two decades. In 2015, 92 million tons of wild species were harvested worldwide – the same amount as in 1995. In contrast, seafood production from

aquaculture increased from 24 million tons to 77 million tons during the same time period, and is still rising to help meet growing demand.

This

situation has come about because of dangerous levels of

over-exploitation of our natural wild stocks to cope with

population growth and food shortages from farming

land.

Examples of over-fishing abound with collapses signaling the

end game wipeout from which fisheries cannot recover.

Why?

This is not yet fully understood by scientists, where if it

was understood, then presumably rekindling of any geographical

region might be a possibility. It is likely that fish

proliferate in an area from years of genetic feeding pattern

programming that non-native species are not privy to. This is

why salmon return to a certain river to spawn. It must come

from generations of pattern building that humans can wipe out

in a few short years. The average fisherman is not an analyst,

he is a working man looking to grab as much cash for his

family in as short a time as possible. He is not worried about

tomorrow's fishermen and conservation.

This

is surely a case for autonomous fishing vessels with

programmed quotas and information dissemination of data for

active management at national and international levels to

ensure that fisheries are not over exploited. While we wait

for technologists to wake up to the call for help, many

fisheries are bound to collapse.

HAKAI

MAGAZINE COSTA RICA DECEMBER 12 2017 - While an intense focus on tourist developments has spurred economic growth, it’s done nothing to decrease poverty and it’s exacerbated the divide between rich and poor along the coast. And as too many local fishermen now chase after too few fish, many along the coast are drawn into a criminal enterprise that is flourishing—cocaine trafficking. Over the past three years, the amount of cocaine trafficked through the country has nearly tripled.

As fisheries along this idyllic looking coast unravel, so does social order.

Jose Angel Palacios is a professor of fisheries resource management at the National University of Costa Rica. He has been studying and assessing the country’s Pacific coast fisheries for over 40 years. As Palacios explains, nearly 95 percent of Costa Rica’s fishermen are based along the Pacific coast. The Gulf of Nicoya, which is shielded from open ocean waves, is an important breeding ground for several species. But according to Palacios, it has been overfished since 1977, and his projections show that the fishery could collapse as soon as 2020. The queen corvina, one of the most valuable food species in the region, could vanish entirely by 2030. “It’s a time bomb,” Palacios says.

To relieve some of the pressure on the stocks, the government closes the fishery for a minimum of three months once a year in the Gulf of Nicoya. But Palacios dismisses the move as inefficient, mismanaged, and based more on politics than science. Originally, he says, the closure was designed to protect valuable shrimp stocks: the government prohibited fishing for shrimp during their reproductive season, and subsidized the fishermen who stayed home, softening the blow to their incomes. But the government eventually extended the closure to include many other species in the gulf—from corvina, snapper, and horse mackerel to barracuda. Today, the annual closure is often delayed, claims Palacios, because the government doesn’t have enough money to pay the fishermen’s subsidies. As a result, boats fish through at least part of the reproductive season, until the government can find the funds necessary for the subsidies.

To make matters worse, local poachers regularly thumb their noses at the government regulations and undermine conservation efforts. They catch thousands of kilograms of fish with dynamite and illegal nets with mesh that’s smaller than permitted, thereby trapping by-catch.

There are about 70 illegal fishing cases a year with poachers escaping jail time.

Some coastal communities have banded together to patrol and protect their local fisheries. They have had some success, but they’re afraid to deal with armed drug traffickers on their own—with good reason. Costa Rica’s murder rate has now crossed the threshold set by the World Health Organization for an epidemic: 10 per 100,000 people. In 2015, officials linked nearly 70 percent of the country’s homicides to the drug trade, and Costa Rica’s Ministry of Public Safety estimates that 85 percent of the cocaine being shipped through the country travels along the Pacific coast.

The coastal city of Puntarenas has a small port where high-end cruise ships call in periodically with decks full of curious passengers. But the cruise-ship port is a small outlier in a city where dilapidated fishing boats crowd private docks. Years of overfishing have left the city in a vulnerable economic position and drug cartels are now exploiting the situation.

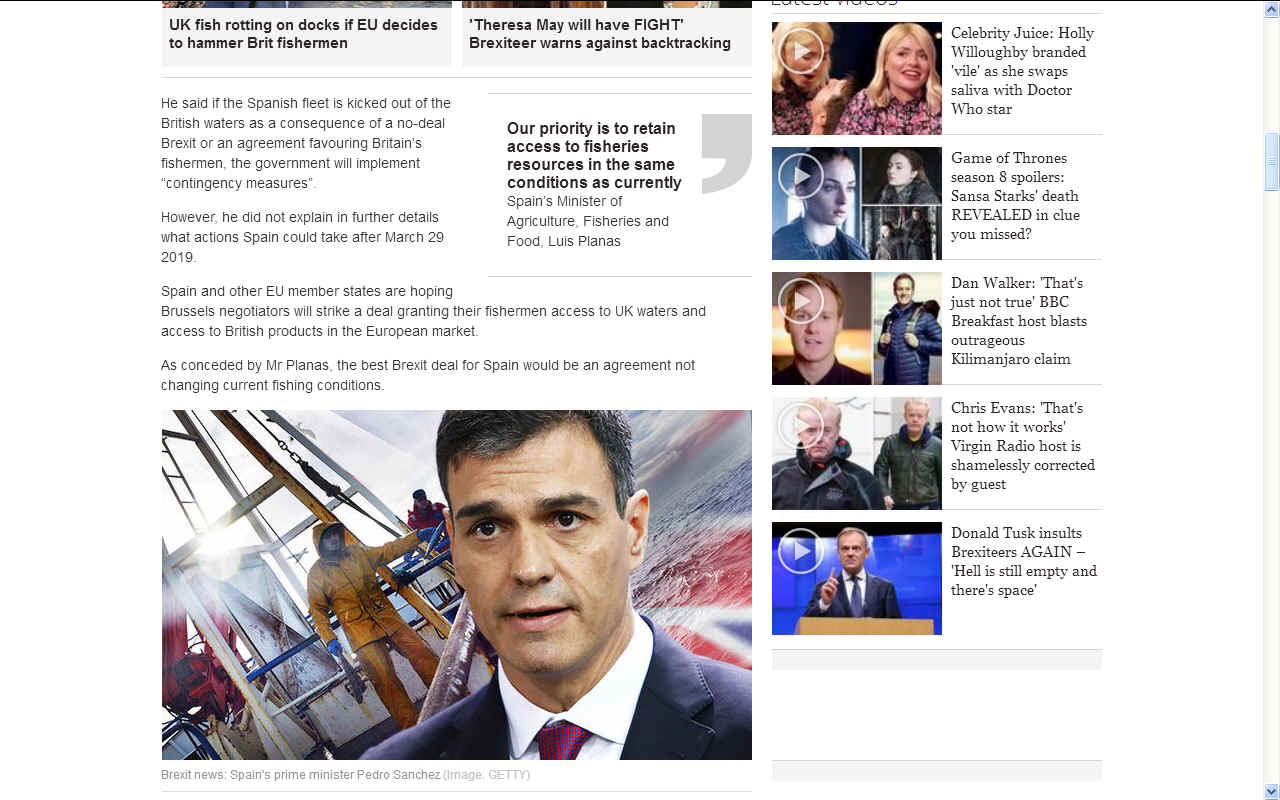

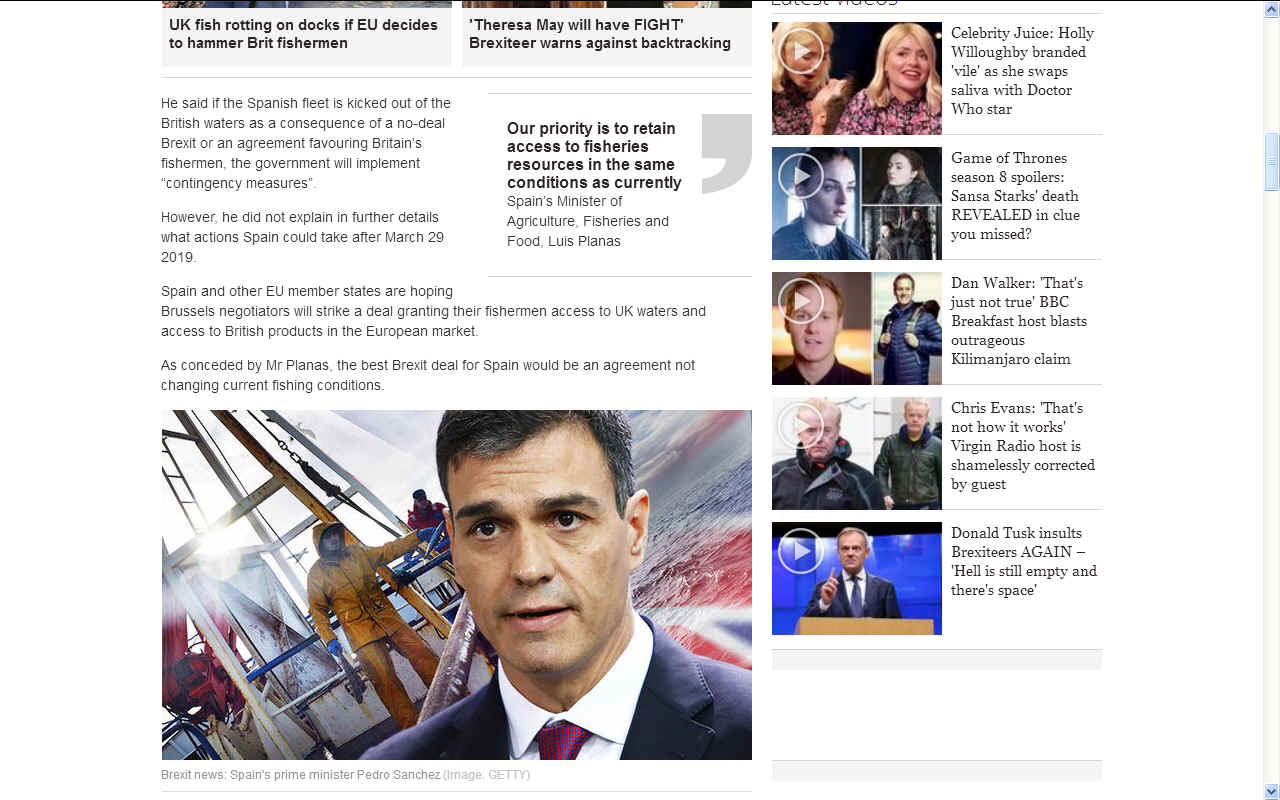

BREXIT

& SPAIN WARNING - DAILY EXPRESS NOV 8 2018 - ready for fishermen to be BANNED from British waters

SPAIN is deeply worried by the “negative consequences” Brexit could have on the nation's fishing industry, one of the country’s minister conceded after revealing the government is taking “measures” to protect Spain's fishermen.

Spain’s Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Luis Planas, spoke to senators in Madrid about Brexit and the consequences the UK withdrawal from the EU could have on his country.

The lack of an agreement between Britain and the European Union just five months ahead of Brexit day is raising concerns in Spain about the knock-on effect it will have on the Spanish fishing industry.

Questioned by José María Cazalis, the senator of the Basque Group, on "the measures that the Government is taking to avoid the possible negative consequences of Brexit in the fishing sector of Spain”, Mr Planas said the government was preparing “answers for any possible scenario”.

He said if the Spanish fleet is kicked out of the British waters as a consequence of a no-deal Brexit or an agreement favouring Britain’s fishermen, the government will implement “contingency measures”.

However, he did not explain in further details what actions Spain could take after March 29 2019.

Spain and other EU member states are hoping Brussels negotiators will strike a deal granting their fishermen access to UK waters and access to British products in the European market.

As conceded by Mr Planas, the best Brexit deal for Spain would be an agreement not changing current fishing conditions.

He said: “Our priority is to retain access to fisheries resources in the same conditions as currently.

“If there is a Brexit deal there will be a transitory period until December 2020, and in the case of no deal, we will have to apply measures to contain the damage.”

The so-called “measures” could affect both the 92 Spanish vessels working and fishing in the UK’s fishing grounds and the 23 boats in the Falkland Island waters

These vessels’ catch in Britain’s water amounts to 9,000 tonnes captured every year, worth a staggering £23.53m (€27m), according to figures released during the debate in the Spanish senate.

Out of these 9,000 tonnes, 4,000 are of hake, worth £12.21m (€14m) alone.

The rest of the catch is composed by rooster and monkfish.

Replying to Mr Planas, Mr Cazalis warned Brussels should take a harsh stance against the UK.

The senator said the EU introduce a limit to the UK produce entering the continent if member states’ vessels were no longer able to fish in UK waters.

He said: “In case London vetoes access, Spain should implement tariffs and limit introduction of UK produce to the

EU.”

EUMOFA

COD & HADDOCK UK CASE STUDY 2017

A

case study by the European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products

(EUMOFA) found that most European markets for Atlantic cod are built on a strong dependency on imports as the main suppliers are extra-EU countries (Norway, Russia and

Iceland). Statistically,

Denmark appears as the largest European trader for fresh Atlantic

cod. But Denmark is a ‘hub’ for Norwegian fish. Generally speaking

the UK is dependent on international sources for seafood supply. Cod

and haddock are the key whitefish species for the UK market. Iceland represents a key source of supply for both cod and haddock into the UK. In 2015, UK imported 108,000 tonnes of cod and exported 12,460

tonnes.

Regarding the price structure in the supply chain for the fresh cod fillet: the filleting is a key step of the process as filleting losses are estimated to account for 45% from the whole fresh cod (gutted, head-on). The ex-factory price is estimated at 47% of the retail price without VAT. The main costs are: processing, packaging, ice, labelling, transport and processor’s margin. 50% of the retail price (including VAT) is the retailer costs and margin.

The EU market for cod is supplied almost exclusively with wild fish.

Aquaculture provides only 3,310 tonnes, coming mainly from

Norway which production fell sharply in 2012 (-53%). Cod farming has been severely reduced since 2010 and the aquaculture for this species proved to be unprofitable due to the availability of wild fish at fair prices. The only EU cod farming company, based in the UK, went bankrupt

in 2008.

THE

GUARDIAN 5

JUNE 2018 - Australia's large fish species declined 30% in past decade, study says.

The number of large fish species in Australian waters has declined by 30% in the past decade, mostly due to excessive fishing, a new study says.

Marine ecology experts are calling for changes to fisheries management after publication of the study by scientists from the University of Tasmania and the University of Technology (UTS), Sydney.

The decade-long study used data from diving surveys by three different bodies – the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the University of Tasmania and Reef Life Survey, a supervised citizen science group – to compare trends in fish populations in unprotected marine areas, protected areas that allow for some fishing, and protected areas that prohibit fishing.

Data was collected repeatedly from 533 sites around Australia from 2005 to 2015 for large fish species – those bigger than 20cm in length, such as snapper, bream and parrotfish.

They found the biomass of large fish had declined by 36% on fished reefs and 18% in marine park zones that allowed for limited fishing.

“Because we were measuring the fish in the fished areas and comparing them to the same species in the unfished areas – and we found substantial differences in the trend over the 10-year period – we can ascribe that to the impact of fishing,” study co-author Trevor Ward, a marine scientist from UTS, said.

He said the work also found there was some level of effect from what they assumed was climate change: “That is, the fish species would still be declining to an extent, even if they weren’t fished, because their habitat is changing.”

Ward said there was a strong need for “highly precautionary fisheries management” but that greater use should also be made of no-take marine protected areas that prohibit recreational or commercial fishing.

“Marine reserves are a natural consequence of wanting to protect both the ocean ecological system and the fisheries so that in the course of things we can safely catch more fish.”

On Tuesday, the Greens urged the government to establish an independent scientific review of Australian fisheries stock.

“This study also shows that marine parks can be successful fisheries management tools but we simply don’t have enough of them or enough protection within them to deliver widespread benefits,” the Greens senator and healthy oceans spokesman, Peter Whish-Wilson, said.

But the assistant minister for agriculture and water resources, Anne Ruston, questioned the paper’s conclusions and said Australia’s sustainably managed commonwealth fisheries were “world-class”.

“The paper contains flawed arguments and conclusions, which are not supported by the weight of publically available evidence,” she said.

“The commercial catch for all fish stocks is set at ecologically sustainable levels and, for the fourth consecutive year, no fishery solely managed by the commonwealth has been subject to overfishing.”

She said the Greens had “failed to present any information to suggest a review is warranted.”

ABOUT

FISHING

Millions of

fisher men and women take to the oceans each day to feed local communities and a growing

global appetite for seafood. Their catch and livelihoods are part of a $190

billion global seafood industry. In all, seafood now makes up

12-20% percent of the animal protein we consume and that demand is expected to double in the next two-decades. The challenge we now face is how to sustainably produce enough fish to meet this demand while maintaining healthy oceans with

sharks, whales,

turtles and other important marine life.

|

Position |

Fisheries

Mt |

Aquaculture

Mt |

Wild-harvest

seaweedsMt |

Farmed

seaweeds

Mt |

|

#1 |

China

17.6 |

China

47.6 |

Chile

0.35 |

China

13.9 |

|

#2 |

Indonesia

6.5 |

India

5.2 |

China

0.26 |

Indonesia

11.3 |

|

#3 |

USA

5.0 |

Indonesia

4.3 |

Norway

0.15 |

Philippines

1.6 |

|

#4 |

India

4.8 |

Vietnam

3.4 |

Japan

0.09 |

South

Korea 1.2 |

|

#5 |

Peru

4.8 |

Bangladesh

2.1 |

Indonesia

0.08 |

North

Korea 0.5 |

|

#6 |

Russia

4.6 |

Norway

1.4 |

Ireland

0.03 |

Japan

0.4 |

|

#7 |

Japan

3.5 |

Egypt

1.2 |

France

0.019 |

Malaysia

0.26 |

|

#8 |

Chile

3.0 |

Myanmar

1.0 |

India

0.019 |

Zanzibar

0.17 |

|

#9 |

Vietnam

2.8 |

Chile

1.0 |

Iceland

0.017 |

Madagascar

0.015 |

|

#10 |

Norway

2.3 |

Thailand

0.9 |

Peru

0.015 |

Solomon

Islands 0.012 |

International

landscape of fisheries, aquaculture and fishmeal production

2015 in millions of tons (Source FAO

2017)

Several decades of

overfishing in most of the world's major fisheries has created large declines in many commercially important fish populations across the world.

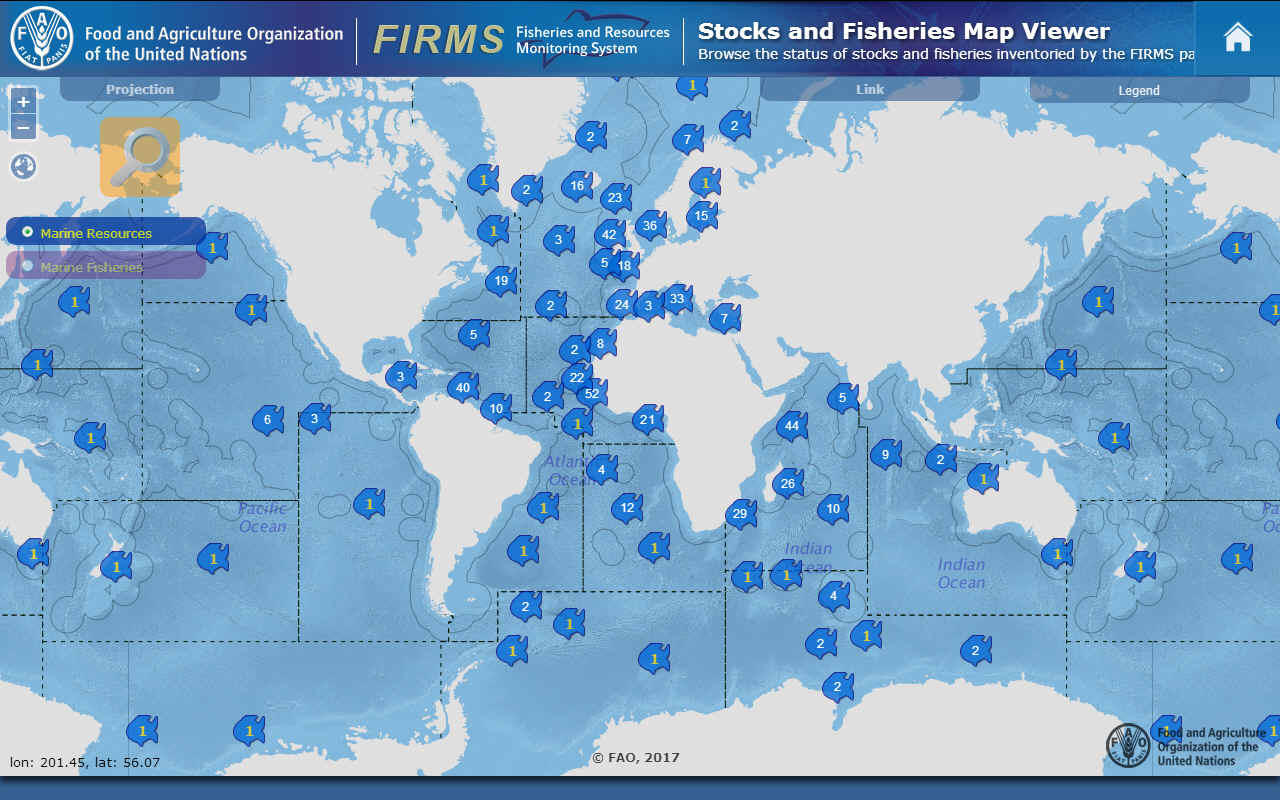

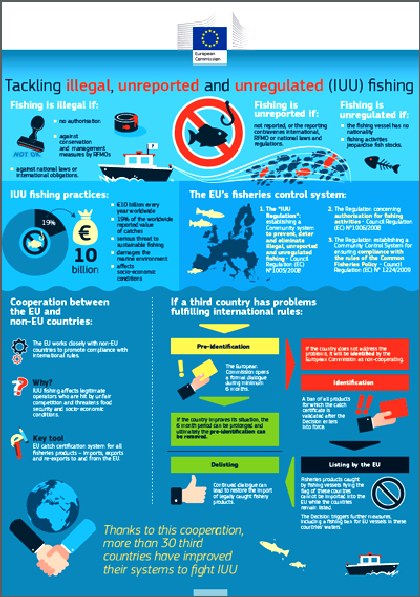

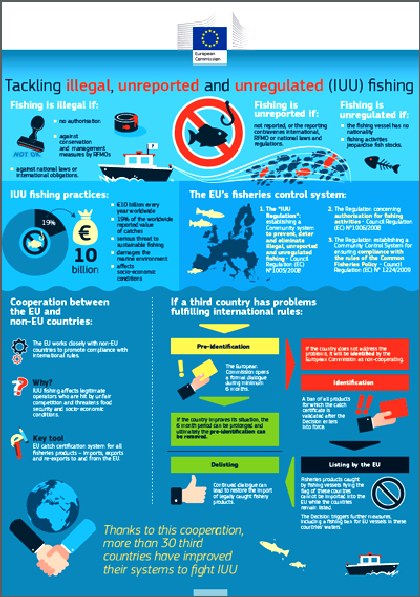

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU)

fishing, today is recognized as a major threat to achieving sustainable fisheries.

By

regulating the fish taken from any geographical fishery, we

are actually doing the fishermen a good turn, because we are

ensuring that there will be fish next year and the year after

that for them to fish. This is what sustainability is all

about.

WHAT

ARE WE EATING AND WHERE HAS IT COME FROM?

All of us can help protect and restore communities’ livelihoods, the health of fish and fisheries, and the health of

coral reefs

with three simple precautions:

1.

By knowing where our fish and seafood come from,

2.

By knowing how the fish are caught, and

3.

By knowing how healthy those fish are.

Only

by knowing what we are eating, where it has come and how it

was caught (EG by a local fisherman using a small boat) from can we decide whether to continue eating away tomorrow’s

fish. If the fish on the shelf is suspect in origin or not labeled

in terms of responsible fishing we can

make a decision that will have a long-lasting impact on the natural environment, as well as the quality of life for people who depend on these

resources - we can decide not to purchase and we can report

our suspicions to the authorities.

SUPERMARKETS

& FISH RETAILERS

Supermarkets

have got a lot to answer for in terms of sustainable

practices. Ultimately, they are responsible for packaging

where their business model dictates to a large extent, how and

in what goods are delivered and displayed. Much of the single

use plastic goes through a supermarket, because that is

where most people shop for their food.

WHAT

IS A FISHERY?

Generally, a fishery is an entity engaged in raising or harvesting fish which is determined by

a local or national authority to be a fishery.

According to the

FAO, a fishery is typically defined in terms of the "people involved, species or type of

fish, area of water or seabed, method of fishing, class of

boats, purpose of the activities or a combination of the foregoing features". The definition often includes a combination of fish and fishers in a region, the latter

fishing for similar species with similar gear types.

A fishery may involve the capture of wild fish or raising fish through fish farming or

aquaculture. Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries and

aquaculture. Overfishing, including the taking of fish beyond sustainable levels, is reducing fish stocks and employment in many world regions. A report by

Prince

Charles' International Sustainability Unit, the New

York-based Environmental Defense Fund and 50in10 published in July 2014 estimated global fisheries were adding $270 billion a year to global GDP, but by full implementation of sustainable fishing, that figure could rise by as much as $50

billion.

TYPES

OF FISHERY

Fisheries are harvested for their value (commercial, recreational or subsistence). They can be saltwater or freshwater, wild or farmed. Examples are the salmon fishery of

Alaska, the cod fishery off the Lofoten islands, the tuna fishery of the Eastern

Pacific, or the shrimp farm fisheries in

China. Capture fisheries can be broadly classified as industrial scale, small-scale or artisanal, and recreational.

Close to 90% of the world’s fishery catches come from oceans and seas, as opposed to inland waters. These marine catches have remained relatively stable since the mid-nineties (between 80 and 86 million tonnes). Most marine fisheries are based near the coast. This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near the coastal shelf, due to the abundance of nutrients available there from coastal upwelling and land runoff. However, productive wild fisheries also exist in open oceans, particularly by seamounts, and inland in lakes and rivers.

Most fisheries are wild fisheries, but farmed fisheries are increasing. Farming can occur in coastal areas, such as with oyster farms, but more typically occur inland, in lakes, ponds, tanks and other enclosures.

There are species fisheries worldwide for finfish, mollusks, crustaceans and echinoderms, and by extension, aquatic plants such as kelp. However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world’s fisheries. Some of these species are herring,

cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid,

shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a million tonnes in 1999, with herring and sardines together providing a harvest of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are harvested in smaller numbers.

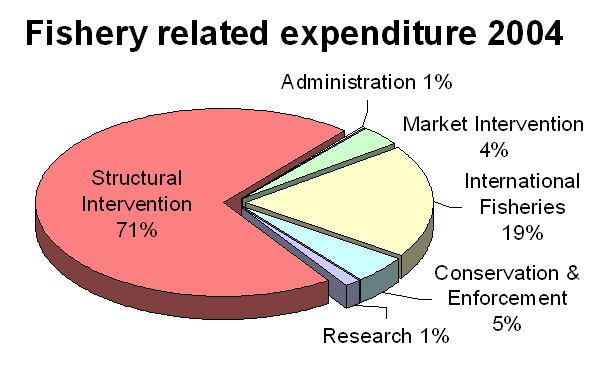

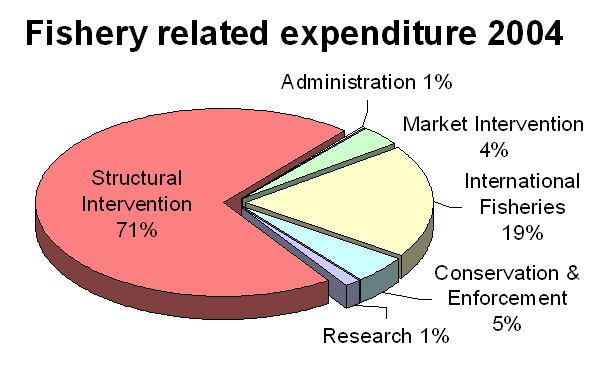

EU

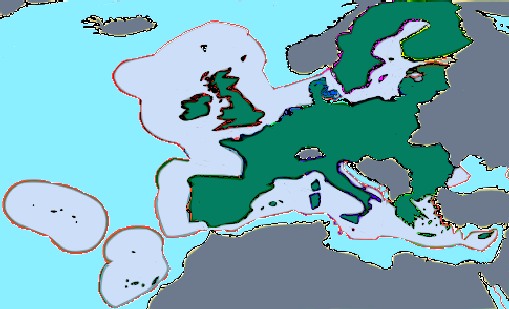

EZZ - The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is the fisheries policy of the European Union (EU). It sets quotas for which member states are allowed to catch each type of fish, as well as encouraging the fishing industry by various market interventions. In 2004 it had a budget of €931 million, approximately 0.75% of the EU budget.

When it came into force, the Treaty of Lisbon formally enshrined fisheries conservation policy as one of the handful of "exclusive competences" reserved for the European Union, to be decided by Qualified Majority Voting. However, general fisheries policy remains a "shared competence" of the Union and its member states. Thus decisions are still made primarily by the Council of the European Union, as was the case previously.

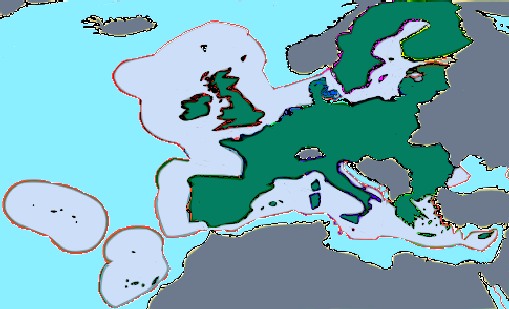

The common fisheries policy was created to manage fish stock for the European Union as a whole. Article 38 of the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which created the European Communities (now European Union), stated that there should be a common policy for fisheries.

The EU's exclusive economic zone EEZ is the largest in the

world at 25 million square kilometres in area. The EU's fishing fleet numbers 88,000 – the second largest in the world – and can fish freely across the European Union, catching nearly six million metric tonnes a year.

EU FISHING

IMPORTANCE IN 2007

Fishing is a relatively unimportant economic activity within the EU. It contributes generally less than 1% to gross national product. In 2007 the fisheries sector employed 141,110 fishermen. In 2007, 6.4 million tonnes of fish were caught by EU countries. The EU fleet has 97,000 vessels of varying sizes. Fish farming produced a further 1 million tonnes of fish and shellfish and employed another 85,000 people. The shortfall between fish catches and demand varies, but there is an EU trade deficit in processed fish products of €3 billion.

The combined EU fishing fleets land about 6 million tonnes of fish per year, of which about 3 million tonnes are from UK waters. The UK’s share of the overall EU fishing catch is only 750,000 tonnes. This proportion is determined by the London Fisheries Convention of 1964 and by the EU's Common Fisheries Policy.

In Fraserburgh, Scotland, the fishing industry creates 40% of employment and a similar figure in Peterhead. They are the EU's largest fishing ports and home to the pelagic vessel fleet.

Fishing fleets are often in areas where other employment opportunities are limited. For this reason, community funds have been made available to fishing as a means of encouraging regional development.

The market for fish and fish products has changed in recent years. Supermarkets are now the main buyers of fish and

they expect steady supplies from their suppliers. Fresh fish sales have fallen, but demand for processed fish and prepared meals has grown. Despite this, employment in fish processing has been falling, with 60% of fish consumed in the EU coming from elsewhere. This is partly due to improvements in the ability to transport fresh fish internationally. Competitiveness of the EU fishing industry has been affected by

the overcapacity of boats and shortages of fish to catch.

DWINDLING

FISH STOCKS - Food

security is a major problem the world will have to face as

the available land for to grow crops reduces in competition

with land for housing, as the population expands. The

situation is far from sustainable and a bubble that will

burst. When the bubble bursts it will cause the deaths of

millions of people, where additional farming will create more

carbon dioxide to heat the climate, making more land barren in

a vicious circle that we must take steps to prevent happening.

Around

10% of the world (700,000,000 million people) rely on the

ocean for food, but in addition to our poor land management

record, we are also polluting the seven seas with plastic that

is toxic - so reducing the number of fish that we might

harvest for food. Aquaculture, is seen as the savior for fish

supply, but fish farming is dependent on ocean and land

derived feeds, hence is more of an icing quick fix than a

really tasty cake.

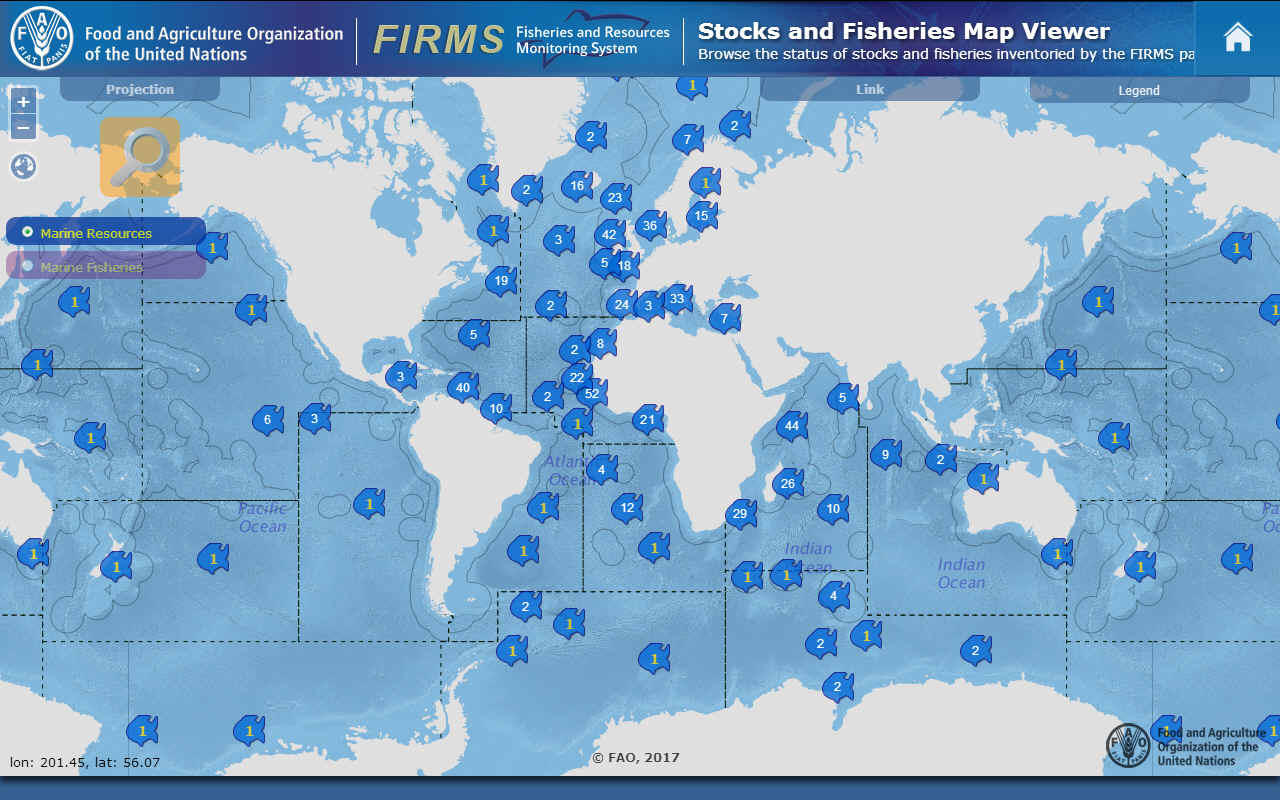

MONITORING

& REGULATION

For any government agency that needs to track more than just the larger commercial ships in its waters,

AIS and VMS mandates do not address the huge population of smaller vessels of interest. This leaves the vast majority of boats in their waters as ‘dark targets’, ultimately spreading an agency’s resources too thinly to monitor all of its

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

NOAA

- Fisheries tracks 473 fish stocks managed by 46 fishery management plans. We have rebuilt 40 stocks since 2000 as a result of our fishery management process. Overfishing and overfished numbers remained near all-time lows in 2015.

FORBES

JULY 24 2017 - TWO THIRDS OF THE WORLD'S SEAFOOD IS OVERFISHED

Most fish companies maximize what they pull from the sea with little concern for the methods used to snare their haul. As a result, a shockingly large percentage of the world’s fisheries are now in decline. With worldwide demand for seafood expected to double in the next two decades, it’s doubtful these companies will take their foot off the gas, though that might not be in their best interest. A recent global survey in Science has estimated that we could see seafood vanish altogether by

2048. Now, the future of the fish industry is looking increasingly vulnerable. This leads one to ponder many important questions, like ‘can companies produce their product more sustainably and feed a growing population without depleting our oceans? Is there, in fact, such a thing as sustainable seafood?’ In order to flesh this out further, I’ve listed a few important truth-cakes to chew on in order comprehend just how big of a net we’ve gotten ourselves caught in.

1. Two-thirds of the worlds fish are overfished and

depleted: 4,714 fisheries were assessed in 2012 (UN Food and Agricultural Organization, 2015), and 32% were at or above the biomass (total mass of fish left in the water) that supports a maximum sustainable yield. Only a third of fisheries overall are fished at levels that allow fish to repopulate. Our choices in the coming years will determine if the majority of fisheries will rebuild or collapse. This is also quite concerning for the 40% of the global population that relies on fish for their food.

2. Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated fishing (in other words, poaching) is estimated to account for

20-30% of the global catch: ‘We are flying blind,’ according to Mark Zimring at The

Nature Conservancy. He states we don’t have the data and compliance to build solid policies that can address this problem adequately. Many fisheries in the world are not routinely assessed at all so there could be even more fisheries facing strong declines and we may not even know it. The Nature Conservancy's electronic monitoring project (GPS, sensors, tracking devices, video cameras on boats, etc) aims to improve their data to get a better understanding of how poaching can be solved. These efforts can also help with product traceability, not to mention addressing the slave labor problems found across the industry.

3. 10% of fish caught in oceans get dumped back in: It’s startling to think that billions of fish are killed each year without reaching the dinner table. It’s abundantly clear that many of the fishing methods we use have a massive impact on the ocean. There’s also the issue with

bycatch (sharks, dolphins, turtles, whales) and faulty gear. Some of the discarded fish is deemed low valued fish, or too diseased to keep.

4. It has been estimated that between 0.97 to 2.7 trillion fish are caught from the wild and killed globally every year: This doesn’t include the billions of fish that are farmed. Fish account for approximately 40% of animal products consumed. (39% vs 26% pigs vs 20% chickens vs 14% cows) These numbers don’t include sports fishing. ‘We now have a fifth more of global fish stocks at worrying levels than we did in 2000. The global environmental impact of overfishing is incalculable and the knock-on impact on coastal economies is simply too great for this to be swept under the rug anymore.'- Lasse Gustavssin, the director of

Oceana.

5. Fish farming is forecasted to overtake wild-caught fish production

for the first time in 2021: Fish farming is taking the seafood industry by storm. For context, farmed fish accounts for 70% of all farmed animals worldwide. This presents a host of problems. For example, shrimp farming has led to the destruction of three million acres of

coastal

wetlands. Some sustainability minded groups fear that fish farming might activate invasive species and disease. The potential for chemical pollution is causing concern as well. For example, there have been reports on high pollution levels from chemicals used to kill lice found in salmon farms. There's no doubt about it, the impact of farmed fish will be substantial.

‘We now have a fifth more of global fish stocks at worrying levels than we did in 2000. The global environmental impact of overfishing is incalculable and the knock-on impact on coastal economies is simply too great for this to be swept under the rug anymore.’ - Lasse Gustavssin, the director of

Oceana.

WILD

SALMON - Salmon spawn in a salmon fishery within the Becharof Wilderness in Southwest Alaska.

VIABLE SOLUTIONS

Eat Differently. The great thing about the free market is that companies will respond to consumer demand. By changing our eating habits, we can start to move the needle in the right direction. The way I see it, we have three options to put a serious dent in the problem we’re facing:

1) Eat more sustainably. For example, go for oysters, clams, mussels, or scallops instead of

tuna,

salmon, or shrimp. This way, there’s little to no bycatch, and it has the added benefit of reducing suffering, as bi-valves likely don’t feel pain due to their lack of central nervous system.

2) Reduce the amount of fish we consume (reducetarian

diet). Simply buying less fish or ordering it less often could go a long way in reducing the amount of fish we take out of the

ocean.

3) Make the switch to plant-based fish products that sidestep seafood altogether. Not only will this be the best option for our oceans, but you can also avoid the many heavy metals (mercury, etc) frequently found in fish by going this route.

Contributor:

Michael Pellman Rowland

Anchovies

| Bass

| Bream

| Catfish

| Clams

| Cod

Coley

| Crabs

| Crayfish

| Eels

| Grouper

| Haddock

| Hake

| Halibut

| Herring

| Jellyfish

Krill

| Lobster

| Mackerel

| Marlin

| Monkfish

| Mullet

| Mussels

| Oysters

| Perch

| Plaice

| Pollock

| Prawns

| Rays

| Sablefish

| Salmon

Sardines

| Scallops

| Sharks

| Shrimp

| Skate

| Sole

| Sprat

| Squid

| Sturgeon

| Swordfish

| Trout

| Tuna

| Turbot

| Whiting

THE ECONOMIST 2014 FEBRUARY

In 1968 an American ecologist, Garrett Hardin, published an article entitled “The Tragedy of the Commons”. He argued that when a resource is held jointly, it is in individuals’ self-interest to deplete it, so people will tend to undermine their collective long-term interest by over-exploiting rather than protecting that asset. Such a tragedy is now unfolding, causing serious damage to a resource that covers almost half the surface of the Earth.

The high seas - the bit of the oceans that lies beyond coastal states’ 200-mile exclusive economic zones

- are a commons. Fishing there is open to all. Countries have declared minerals on the seabed “the common heritage of mankind”. The high seas are of great economic importance to everyone

- fish is a more important source of protein than beef—and getting more so. The number of patents using DNA from sea-creatures is rocketing, and one study suggests that marine life is a hundred times more likely to contain material useful for anti-cancer drugs than is terrestrial life.

Yet the state of the high seas is deteriorating (see article). Arctic ice now melts away in summer. Dead zones are spreading. Two-thirds of the fish stocks in the high seas are over-exploited, even more than in the parts of the oceans under national control. And strange things are happening at a microbiological level. The oceans produce half the planet’s supply of oxygen, mostly thanks to chlorophyll in aquatic algae. Concentrations of that chlorophyll are falling. That does not mean life will suffocate. But it could further damage the

climate, since less oxygen means more

carbon

dioxide.

For tragedies of the commons to be averted, rules and institutions are needed to balance the short-term interests of individuals against the long-term interests of all users. That is why the dysfunctional policies and institutions governing the high seas need radical reform.

OCEAN

- The EU rules to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) depletes fish stocks, destroys marine habitats, distorts competition, puts honest fishers at an unfair disadvantage, and weakens costal communities, particularly in developing countries.

The EU is working to close the loopholes that allow illegal operators to profit from their activities:

* The EU Regulation to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) entered into force on 1 January 2010. The Commission is working actively with all stakeholders to ensure coherent application of the IUU Regulation.

* Only marine fisheries products validated as legal by the competent flag state or exporting state can be imported to or exported from the EU.

* An IUU vessel list is issued regularly, based on IUU vessels identified by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations.

* The IUU Regulation can take steps against statesSearch for available translations of the preceding link••• that turn a blind eye to illegal fishing activities: first it issues a warning, then it can identify and black list them for not fighting IUU fishing.

* EU operators who fish illegally anywhere in the world, under any flag, face substantial penalties proportionate to the economic value of their catch, which deprive them of any profit.

NET

LOSS

The first target should be fishing subsidies. Fishermen, who often occupy an important place in a country’s self-image, have succeeded in persuading governments to spend other people’s money subsidising an industry that loses billions and does huge environmental damage. Rich nations hand the people who are depleting the high seas $35 billion a year in cheap fuel, insurance and so on. The sum is over a third of the value of the catch. That should stop.

Second, there should be a global register of fishing vessels. These have long been exempt from an international scheme that requires passenger and cargo ships to carry a unique ID number. Last December maritime nations lifted the exemption

- a good first step. But it is still up to individual countries to require fishing boats flying their flag to sign up to the ID scheme. Governments should make it mandatory, creating a global record of vessels to help crack down on illegal high-seas fishing. Somalis are not the only pirates out there.

Third, there should be more marine reserves. An eighth of the Earth’s land mass enjoys a measure of legal protection (such as national-park status). Less than 1% of the high seas does. Over the past few years countries have started to set up protected marine areas in their own economic zones. Bodies that regulate fishing in the high

seas should copy the idea, giving some space for fish stocks and the environment to recover.

But reforming specific policies will not be enough. Countries also need to improve the system of governance. There is a basic law of the sea signed by most nations (though not America, to its discredit). But it contains no mechanisms to enforce its provisions. Instead, dozens of bodies have sprung up to regulate particular activities, such as shipping, fishing and mining, or specific parts of the oceans. The mandates overlap and conflict. Non-members break the rules with impunity. And no one looks after the oceans as a whole.

A World Oceans Organisation should be set up within the UN. After all, if the UN cannot promote collective self-interest over the individual interests of its members, what is it good for? Such an organisation would have the job of streamlining the impenetrable institutional tangle. But it took 30 years to negotiate the law of the sea. A global oceans body would probably take

longer - and the oceans need help now.

So in the meantime the law of the sea should be beefed up. It is a fine achievement, without which the oceans would be in an even worse state. But it was negotiated in the 1970s before the rise of environmental concerns, so contains little on biodiversity. And the regional fishing bodies, currently dominated by fishing interests, should be opened up to scientists and charities. As it is, the sharks are in charge of the fish farm.

This would not solve all the problems of the oceans. Two of the

biggest - acidification and pollution - emanate from the land. Much of the damage is done within the 200-mile limit. But institutional reform for the high seas could cut overfishing and, crucially, change attitudes. The high seas are so vast and distant that people behave as though they cannot be protected or do not need protection. Neither is true. Humanity has harmed the high seas, but it can reverse that damage. Unless it does so, there will be trouble brewing beneath the waves.

IDYLLIC

- Before industrialization and the advent of motor driven

fishing craft, man could not plunder the oceans. We all enjoy

the benefits of industry and mechanization, but should we be

looking backwards for way to enjoy a healthy meal from the

sea.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/1042334/brexit-news-brexit-fishing-british-waters-brexit-latest-deal

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2018/07/illegal-giant-fish-cambodia-vietnam-cuisine-delicacy-wildlife-watch/

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jun/05/australias-large-fish-species-declined-30-in-past-decade-study-says

http://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/

https://www.hakaimagazine.com/

http://www.noaa.gov/fisheries

https://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/cfp/illegal_fishing_en

http://www.eumofa.eu/

https://www.hakaimagazine.com/features/fish-drugs-and-murder/

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/11/061102-seafood-threat.html

https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21596942-new-management-needed-planets-most-important-common-resource-tragedy-high

https://www.nature.org/

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X14000918

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-environment-fish-idUSKBN19H1A8

https://reducetarian.org/

http://fishcount.org.uk/published/std/fishcountstudy.pdf

http://mangroveactionproject.org/shrimp-farming/

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/07/global-fish-production-approaching-sustainable-limit-un-warns

http://oceana.org/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelpellmanrowland/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelpellmanrowland/2017/07/24/seafood-sustainability-facts/#44b2c7eb4bbf

http://www.exactearth.com/applications/illegal-fishing

https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/urgentissues/oceans/future-of-fisheries/index.htm

https://blog.nature.org/conservancy/2015/04/13/we-have-all-been-eating-tomorrows-fish/

OCEAN

CONDITIONER - The fishing industry stands to benefit the

most from ocean conditioning and healthier oceans. SeaVax

is designed to operate in fleets

to target sea-borne waste before it settles on the ocean floor

where nobody can recover it. There is nothing like it in

existence today, though thankfully, other ideas for trapping plastic waste

are being developed in tandem, such as that of Boyan

Slat and the Seabin.

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2023. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital.

|