|

BAY

OF BENGAL - AGENDA 2030

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

THE

GUARDIAN - Is a newspaper that covers many aspects of

the effect that human activity is having on our precious blue

planet .

The

United Nation's sustainability

development goals (SDGs) now firmly place blue growth on

the 2030 Agenda, beginning with a 5 year period from 2018 to

2023. The Bay of Bengal is an area that is of particular

concern where so many people depend on food from the sea, and

where a mix of pollution and intensive fishing practices put

the area at risk.

THE

GUARDIAN JAN 31 2017

The Bay of Bengal’s basin contains some of the most populous regions of the earth. No less than a quarter of the world’s

population is concentrated in the eight countries that border the

bay 1. Approximately 200 million people live along the Bay of Bengal’s coasts and of these a major proportion are partially or wholly dependent on its

fisheries 2.

For the majority of those who depend on it, the Bay of Bengal can provide no more than a meagre living: 61% of India’s fisherfolk already live below the poverty line. Yet the numbers dependent on fisheries are only likely to grow in years to come, partly because of

climate change. In southern India drought and

water scarcity have already induced tens of thousands of

farmers to join the fishing

fleet 3. Rising sea levels are also likely to drive many displaced people into the fishing industry.

But the fisheries of the Bay of Bengal have been under pressure for decades and are now severely

depleted 4. Many once-abundant species have all but disappeared. Particularly badly affected are the species at the top of the

food

chain. The bay was once feared by sailors for its man-eating

sharks; they are now rare in these waters. Other apex predators like grouper, croaker and

rays have also been badly hit. Catches now consist mainly of species like

sardines, which are at the bottom of the marine food

web 5.

CHILD

LABOUR - Children unload fish from a boat at San Pya fish market in Yangon, Myanmar. The opening up of the economy has triggered a demand for

child labour.

Good intentions have played no small part in creating the current situation. In the 1960s, western aid agencies encouraged the growth of trawling in India, so that fishermen could profit from the demand for prawns in foreign markets. This led to a “pink

gold rush”, in which prawns were trawled with fine mesh

nets that were dragged along the sea floor. But along with hauls of “pink gold” these nets also scooped up whole seafloor ecosystems as well as vulnerable species like

turtles,

dolphins, sea snakes,

rays and

sharks. These were once called bycatch, and were largely discarded. Today the collateral damage of the trawling industry is processed and sold to the fast-growing poultry and aquaculture industries of the

region 6. In effect, the processes that sustain the Bay of Bengal’s

fisheries are being destroyed in order to produce dirt-cheap chicken feed and

fish feed.

The aid that flowed in after the massive tsunami of 2004 also had certain unintended

consequences 7. It led to the modernization and expansion of the small-scale fisheries sector, which generated an illusory boom followed by a bust.

In recent decades the governments of the nations that surround the Bay of Bengal have striven to expand and encourage their fisheries. But unfortunately these efforts have often ignored questions of long-term sustainability. Although attempts have been made to regulate fishing in the bay they have been largely ineffective.

In the 1980s and 90s, fisheries expanded into new grounds and began to target new species and for a while there was an increase in

catches 5. But catch rates began to decline in the late 1990s and trawlers were forced to move farther and farther from their home waters. This in turn has created a little-noticed grid of conflict. In 2015 Sri Lankan authorities claimed to have spotted 40,544 Indian

trawlers in Sri Lanka’s territorial

waters 8. Seventy trawlers were seized and 450 fishermen were arrested. At least 100 deaths have been

reported 9. Conversely, many Sri Lankan tuna fishermen have also been arrested in India. On the other side of the subcontinent, large numbers of Indian fishermen are frequently arrested in

Pakistan: 220 of them were released in December 2016, as a goodwill gesture.

In Myanmar, until a ban was enacted in 2014, the catch collected by foreign fishing boats was 100 times greater than that of local

fishermen 10. In the troubled Arakan region, where 43% of the population is dependent on fisheries, catches have declined so steeply that many families are mired in

debt 11. Conflicts over fisheries and other resources are a significant but largely unnoticed aspect of the explosive tensions of the region.

The Mergui archipelago on the Thai-Myanmar border is one of the more secluded parts of the Bay. In the late 19th century an English fisheries officer described this area as being “literally alive with

fish” 1. Today the archipelago’s sparsely populated islands remain pristinely beautiful while some of its underwater landscapes present scenes of utter devastation. Fish stocks have been decimated by methods that include cyanide poisoning. The region was once famous for its coral reefs; these have been ravaged by

dynamite-fishing and climate-change induced bleaching.

Yet the exploitation of these waters continues without check. At night specially equipped, long-armed boats

materialize around the islands and shine high-powered green lights into the water to attract

plankton and the

squid that follow in their wake. After nightfall, a glow that is bright enough to be visible from outer

space 12 hangs above the archipelago, like a miasmic fog. These squid boats, some of which are probably crewed by men who have been trafficked like

slaves

13, help to make Thailand the world’s largest exporter of squid – at least for the time being.

At the same time the bay’s ecosystems are also being disrupted by other environmental pressures. Several large rivers empty into the bay, carrying vast tides of untreated sewage, plastic, industrial waste and effluent from the

agriculture and aquaculture

industries 14. The impact of this pollution could be catastrophic. The high load of organic pollutants, coupled with the diminution of the fish that keep them in control, could lead to massive

plankton blooms, further reducing the water’s

oxygen content.

SATELLITES

- Green spots seen from the International Space Station are the lights of fishing boats used to attract squid across the

Gulf of

Thailand. The photograph is from

ISS/Nasa where many other agencies also contribute to our understanding

of the world.

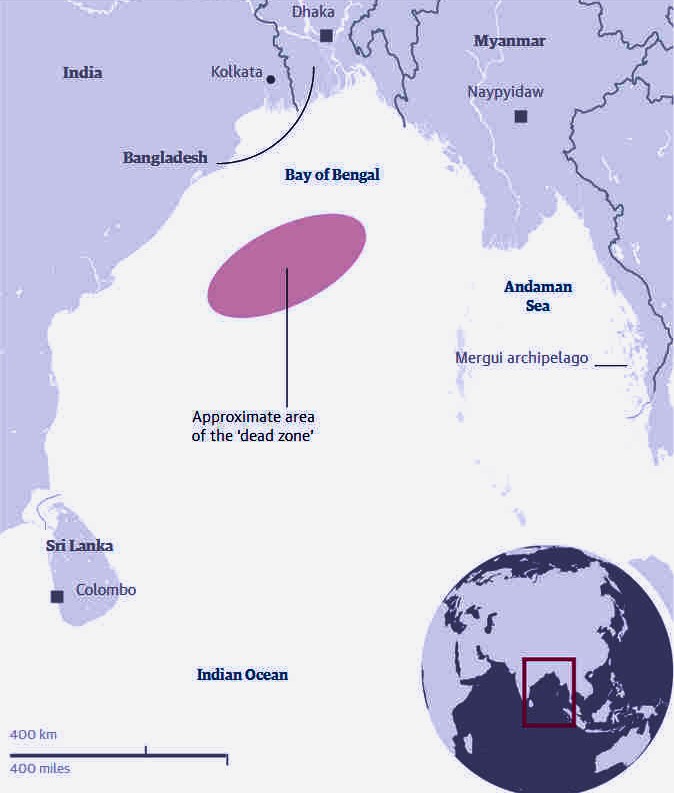

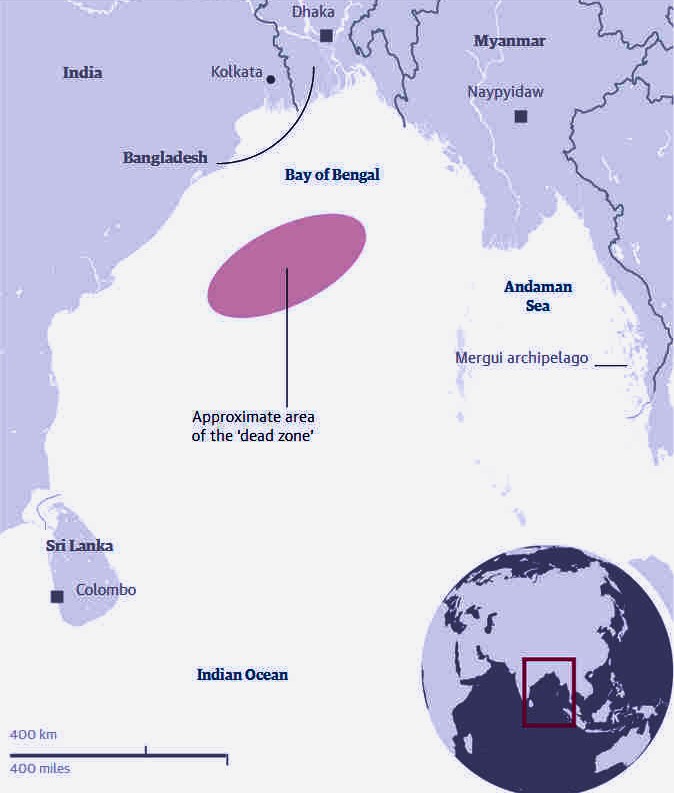

Last month a multinational team of scientists reported an alarming finding – a very large “dead zone” has appeared in the bay. Apart from sulphur-oxidising bacteria and marine worms, few creatures can live in these oxygen-depleted

waters 15. This zone already spans some 60,000 sq km and appears to be

growing 16.

The dead zone of the Bay of Bengal is now at a point where a further reduction in its oxygen content could have the effect of stripping the water of

nitrogen, a key nutrient. This transition could be triggered either by accretions of pollution or by changes in the monsoons, a predicted effect of

global

warming.

What is unfolding in the bay is a catastrophic convergence of flawed policy, economic over-exploitation, unsustainable forms of

waste management, and climate change impacts that are intensifying in unpredictable ways. The scientists who identified the bay’s dead zone warn that this stretch of ocean is approaching a tipping point that will have serious consequences for the planet’s

oceans and the global nitrogen cycle.

Should the bay’s fisheries collapse there will also be very serious human consequences, including intensified conflict and mass displacement. If millions of people lose their livelihoods then we can be sure that the resultant churning of populations will create huge new streams of migration, across the bay, the

Indian

Ocean, and indeed, the planet. Recent refugee flows in the region suggest that such a process may have already begun.

For these issues to be addressed there needs to be a sea change in governmental attitudes and policies. For too long the governments of the region, often with international encouragement, have looked upon the sea as a bottomless resource pit to be despoiled at will. They need instead to view it as a wilderness that requires conservation and informed management, in consultation with the communities that are dependent on it. The situation demands carefully crafted solutions since it involves millions of livelihoods that are already imperilled by the dwindling of the bay’s resources.

• Amitav Ghosh is a novelist and non-fiction writer. His most recent book is The Great Derangement:

Climate Change and the Unthinkable.

• Aaron Savio Lobo has a PhD in marine conservation from the

University of Cambridge. He is currently a technical advisor for the Indo-German Biodiversity program of the GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit ) in

India. The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of his organisation.

BUSY

MARKET - A fish market at Nagor harbour in Nagapattinam, Tamil Nadu, India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Amrith, S. Crossing the Bay of Bengal: the furies of nature and the fortunes of migrants. (Harvard University Press Cambridge, MA, 2013).

2. BOBLME. Results and achievements of the BOBLME Project. (2015).

3. Swathilekshmi, P. S. & Johnson, B. Migrant labourers in the primary sector of marine fisheries: A case study in Karnataka. 38 (Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, 2013).

4. Vivekanandan, E., Srinath, M. & Kuriakose, S. Fishing the marine food web along the Indian coast. Fish. Res.72, 241–252 (2005).

5. Bhathal, B. & Pauly, D. ‘Fishing down marine food webs’ and spatial expansion of coastal fisheries in India, 1950–2000. Fish. Res.91, 26–34 (2008).

6. Lobo, A. S., Balmford, A., Arthur, R. & Manica, A. Commercializing bycatch can push a fishery beyond economic extinction. Conserv. Lett.3, 277–285 (2010).

7. Pomeroy, R. S., Ratner, B. D., Hall, S. J., Pimoljinda, J. & Vivekanandan, V. Coping with disaster: Rehabilitating coastal livelihoods and communities. Mar. Policy30, 786–793 (2006).

8. Scholtens, J. Fishing for access in transboundary waters. The reproduction of fishers’ marginality in post-war northern Sri Lanka. (University of Amsterdam, 2016).

9. Suryanarayan, V. & Swaminathan, R. Fishing in Palk Bay: contested territory or common heritage? Thinking out of the box. (Ganesh and Co.).

10. San Yamin Aung. Myanmar bans foreign fishing from its waters. Asia Sentinel (2014).

11. Ei Cherry Aung. As catch and sales fall, Burma’s fishermen sink into debt. The Irrawaddy (2017).

12. Schonhardt, S. What’s the one thing in Thailand visible from space? The Wall Street Journal (2014).

13. Jones, S. Trafficked into slavery on a Thai fishing boat: “I thought I’d die there”. The Guardian (2015).

14. Kaly, U. L. Review of land-based sources of pollution to the coastal and marine environments in the BOBLME Region. 100 (FAO-BOBLME Programme, 2004).

15. Bristow, L. A. et al. N2 production rates limited by nitrite availability in the Bay of Bengal oxygen minimum zone. Nat. Geosci10, 24–29 (2017).

16. Jayaraman, K. S. Dead zone found in Bay of Bengal. Nature Asia (2016).

By Amitav Ghosh and Aaron Savio Lobo

GLOBAL

WASTE PROBLEM - The

above views of planet earth as global views show us the Indian

Ocean gyres and estimates of plastic waste in

(thousands) numbers of pieces of plastic waste per square kilometer

of sea. The Pacific

Ocean gyres are held to be the worst at the moment.

INDIAN

OCEAN RIM ASSOCIATION (IORA)

According to their website, the Blue Economy was recognised as a priority focus area at the 14th IORA Ministerial Meeting in Perth, Australia, on 9 October 2014. The

Blue Economy captured the attention of all IORA Member States due to its growing global interest and potential and for being recognised as the top priority for generating employment, food security, poverty alleviation and ensuring sustainability in business and economic models in the

Indian

Ocean. Considering its wide range of valuable resources, the Blue Economy is gaining increasing interest in IORA Member States that are all committed to the establishment of a common vision that would make this sector a driver for balanced economic development in the Indian Ocean Rim region.

Since 2014, several capacity building programmes have been carried out covering a wide range of areas, includinginter alia: fisheries and aquaculture; seafood processing, handing and storage; seafood quality and safety; seaport and shipping; maritime connectivity; and ocean forecasting. The First IORA Ministerial Blue Economy Conference (BEC) was held in Mauritius on 3 September 2015 where the

Blue Economy Declaration was adopted. Reflecting on the global trends, this Declaration seeks to harness oceans and maritime resources to drive economic growth, job creation and innovation, while safeguarding sustainability and environmental protection.

With the new challenges that the Blue Economy sector is facing, IORA is striving to promote this important sector as a driver for sustainable development; research and development; investment, technology transfer, with capacity building being crucial in exploring the full potential of the oceans for the socio-economic benefit of the region.

IORA

CONTACTS

IORA Secretariat

Indian Ocean Rim Association

3rd Floor | Tower I | NeXTeracom Building

Cybercity | Ebene | Republic of Mauritius

E-mail: hq@iora.net

Phone: +230 454 1717 | Fax : +230 468 1161

IORA Secretariat

H.E. K V Bhagirath (Mr)

Secretary-General

E-mail: hq@iora.net

Phone: +230 454 6715

Firdaus Dahlan (Mr)

Director (Indonesia)

E-mail: hq@iora.net

Phone: +230 454 1717

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jan/31/bay-bengal-depleted-fish-stocks-pollution-climate-change-migration

http://www.iora.net/blue-economy/blue-economy.aspx

FISHING

NETS - MICROBEADS - MICRO

PLASTICS - OCEAN GYRES - OCEAN WASTE - PLASTIC

- POPS

GANGES

- NILE

AEGEAN

- ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- AMBRACIAN

GULF

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC

- BALTIC

- BAY

BENGAL - BAY

BISCAY - BERING

- BLACK

- CARIBBEAN

- CASPIAN

- CORAL

- EAST

CHINA SEA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC

- GUANABARA

- GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN

-

IRC - IONIAN - IRISH

- MEDITERRANEAN

- NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN

GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - RED

- SARGASSO

- SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN - TYRRHENIAN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2025. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital. The names Amphimax™

and SeaVax™

are trademarks.

|