|

THE

IRISH SEA

ABOUT - CLIMATE

CHANGE - CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - OCEAN

PLASTIC

PLEASE

USE OUR A-Z INDEX

TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

CONTAMINATION

- The Irish Sea has been described by Greenpeace as the most radioactively contaminated sea in the world with some "eight million litres of nuclear waste" discharged into it each day from Sellafield reprocessing plants, contaminating seawater, sediments and marine life.

Ireland is often referred to as the 32 counties, with its two states, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, nicknamed respectively the Six Counties and the 26 Counties. The counties were a creation of British rule in Ireland and were set up in the 19th century to provide a framework for local government.

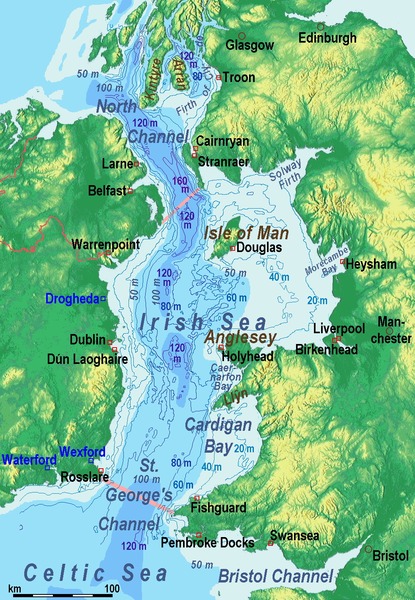

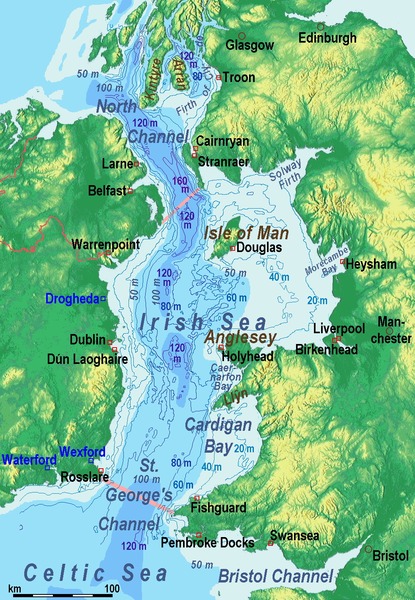

The Irish Sea separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain; linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel, and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of

Scotland in the north by the Straits of Moyle. Ireland and all countries that comprise the

United Kingdom are on its shoreline: Scotland on the north, England on the east, Wales on the southeast, and Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland on the west.

Anglesey, Wales, is the largest island in the Irish Sea. The second in size is the Isle of Man and the sea may occasionally, but rarely, be referred to as the Manx Sea. The Irish Sea is of significant economic importance to regional trade, shipping and transport, fishing, and power generation in the form of wind power and

nuclear power plants. Annual traffic between Great Britain and Ireland amounts to over 12 million passengers and 17 million tonnes (17,000,000 long tons; 19,000,000 short tons) of traded goods.

Because Ireland has neither tunnel nor bridge to connect it with Great Britain, the vast majority of heavy goods trade is done by sea. Northern Ireland ports handle 10 million tonnes (9,800,000 long tons; 11,000,000 short tons) of goods trade with the rest of the United Kingdom annually; the ports in the Republic of Ireland handle 7.6 million tonnes (7,500,000 long tons; 8,400,000 short tons), representing 50% and 40% respectively of total trade by weight.

The Port of Liverpool handles 32 million tonnes (31,000,000 long tons; 35,000,000 short tons) of cargo and 734,000 passengers a year. Holyhead port handles most of the passenger traffic from Dublin and Dún Laoghaire ports, as well as 3.3 million tonnes (3,200,000 long tons; 3,600,000 short tons) of freight.

Ports in the Republic handle 3,600,000 travellers crossing the sea each year, amounting to 92% of all Irish Sea travel.

Ferry connections from Wales to Ireland across the Irish Sea include Fishguard Harbour and Pembroke to Rosslare, Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire and Holyhead to Dublin. From Scotland, Cairnryan connects with both Belfast and Larne. There is also a connection between Liverpool and Belfast via the Isle of Man or direct from Birkenhead. The world's largest car ferry, Ulysses, is operated by Irish Ferries on the Dublin Port–Holyhead route;

Stena Line also operates between Britain and Ireland.

COASTAL

TOURISM

Coastal Tourism is based on a unique resource combination at the border of land and sea environments: sun, water, beaches, outstanding scenic views, rich biological diversity (birds, whales, corals etc), sea food and good transportation infrastructure. Based on these resources, various profitable services have been developed in many coastal destinations such as well maintained beaches, diving, boat-trips, bird watching tours, restaurants or medical facilities.

In the middle of the 20th century coastal tourism in Europe turned into mass tourism and became affordable for nearly everyone. Today, 65% of the

European holiday makers prefer the coast (E.C., 2011). The coastal tourism sector in Europe is getting increasingly competitive, with tourists expecting more quality for the lowest possible price. Today’s tourists expect more than sun, sea and sand, as was the case two decades ago. They demand a wide variety of associated leisure activities and experiences including sports, cuisine, culture and natural attractions. At the same time, local people in traditional tourist destinations are increasingly anxious to preserve their own identity, their environment and their natural, historic and cultural heritage from negative impacts.

CHANNELS -

Saint George’s Channel, wide passage extending for 100 miles (160 km) between the Irish Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean. It has a minimum width of 47 miles (76 km) between Carnsore Point (near Rosslare, Ire.) and historic St. David’s Head (Wales)

North Channel, strait linking the Irish Sea with the North Atlantic Ocean and reaching a minimum width of 13 miles (21 km) between the Mull of Kintyre (Scotland) and Torr Head (Northern Ireland). It runs northwest-southeast between Scotland and Northern Ireland and includes the larger Arran and Gigha islands.

The North Channel (known in Irish and Scottish Gaelic as Sruth na Maoile, in Scots as the Sheuch and alternatively in English as the Straits of Moyle or Sea of Moyle) is the strait between north-eastern Northern Ireland and south-western Scotland. It connects the Irish Sea with the Atlantic Ocean, and is part of the marine area officially classified as the "Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland" by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO).

The southern boundary of the strait is a line joining the Mull of Galloway and Ballyquintin Point. The northern boundary is a line joining Portnahaven and Benbane Head. The narrowest part of the strait is between the Mull of Kintyre and Torr Head where its width is 21 kilometres (13 mi; 11 nmi). The deepest part is called Beaufort's Dyke.

The Channel was a favourite haunt of privateers preying on British merchant shipping in wars until the 19th century; in 1778, during the American Revolutionary War it was also the site of a naval duel between American captain John Paul Jones's Ranger and the Royal Navy's Drake. It is crossed by many ferry services. In 1953, it was the scene of a serious maritime disaster, the sinking of the ferry Princess Victoria.

RADIOACTIVE

CONTAMINATION

Low-level radioactive waste has been discharged into the Irish Sea as part of operations at Sellafield since 1952. The rate of discharge began to accelerate in the mid- to late 1960s, reaching a peak in the 1970s and generally declining significantly since then. As an example of this profile, discharges of plutonium (specifically 241Pu) peaked in 1973 at 2,755 terabecquerels (74,500 Ci) falling to 8.1 TBq (220 Ci) by 2004. Improvements in the treatment of waste in 1985 and 1994 resulted in further reductions in radioactive waste discharge although the subsequent processing of a backlog resulted in increased discharges of certain types of radioactive waste. Discharges of technetium in particular rose from 6.1 TBq (160 Ci) in 1993 to a peak of 192 TBq (5,200 Ci) in 1995 before dropping back to 14 TBq (380 Ci) in 2004. In total 22 petabecquerels (590 kCi) of 241Pu was discharged over the period 1952 to 1998. Current rates of discharge for many radionuclides are at least 100 times lower than they were in the 1970s.

Analysis of the distribution of radioactive contamination after discharge reveals that mean sea currents result in much of the more soluble elements such as caesium being flushed out of the Irish Sea through the North Channel about a year after discharge. Measurements of technetium concentrations post-1994 has produced estimated transit times to the North Channel of around six months with peak concentrations off the northeast Irish coast occurring 18–24 months after peak discharge. Less soluble elements such as plutonium are subject to much slower redistribution. Whilst concentrations have declined in line with the reduction in discharges they are markedly higher in the eastern Irish Sea compared to the western areas. The dispersal of these elements is closely associated with sediment activity, with muddy deposits on the seabed acting as sinks, soaking up an estimated 200 kg (440 lb) of plutonium. The highest concentration is found in the eastern Irish Sea in sediment banks lying parallel to the Cumbrian coast. This area acts as a significant source of wider contamination as radionuclides are dissolved once again. Studies have revealed that 80% of current sea water contamination by caesium is sourced from sediment banks, whilst plutonium levels in the western sediment banks between the Isle of Man and the Irish coast are being maintained by contamination redistributed from the eastern sediment banks.

The consumption of

seafood harvested from the Irish Sea is the main pathway for exposure of

humans to radioactivity.[38] The environmental monitoring report for the period 2003 to 2005 published by the Radiological Protection Institute of Ireland (RPII) reported that in 2005 average quantities of radioactive contamination found in seafood ranged from less than 1 Bq/kg (12 pCi/lb) for fish to under 44 Bq/kg (540 pCi/lb) for

mussels. Doses of man-made radioactivity received by the heaviest consumers of seafood in Ireland in 2005 was 1.10 μSv (0.000110 rem). This compares with a corresponding dosage of radioactivity naturally occurring in the seafood consumed by this group of 148 μSv (0.0148 rem) and a total average dosage in Ireland from all sources of 3,620 μSv (0.362 rem). In terms of risk to this group, heavy consumption of seafood generates a 1 in 18 million chance of causing

cancer. The general risk of contracting cancer in Ireland is 1 in 522. In the UK, the heaviest seafood consumers in Cumbria received a radioactive dosage attributable to Sellafield discharges of 220 μSv (0.022 rem) in 2005. This compares to average annual dose of naturally sourced radiation received in the UK of 2,230 μSv (0.223 rem).

IRISH TECH NEWS

FEB 7 2019 - Researchers at the Irish Composites Centre (IComp), in University of Limerick’s Bernal Institute, have developed a solution for the conversion of waste plastic bottles into high-performance composites for many applications, including car and off-the-road vehicle parts. This advanced research initiative has the potential to have a real impact on solving one of the world’s leading environmental problems – responsible disposal of used plastics – and it has won funding from Enterprise Ireland and the Environmental Protection Agency to further support its development.

PLASTIC PROBLEM

There is clearly a plastic problem in Irish

rivers. For example, the River Liffey at the Strawberry Beds outside Dublin. When the

river Liffey is low, plastic bags can be seen hanging like vegetation out of trees normally submerged in the

water. This plastic will end up, like the Liffey’s waters, entering the Irish Sea.

Ocean currents can transport plastic huge distances and computer models have shown that some plastics can travel more than 1,000 km in 60 days. So a piece of plastic could enter the sea in Dublin at the start of April, and end up floating off the coast of Lisbon by the end of May. It’s an international problem.

Amy Lusher, formerly a researcher at NUI Galway, and Simon Berrow, Chief Scientific Officer of the Irish

Whale and

Dolphin Group have carried out pioneering research in the problem of plastics at sea.

In May 2013, the two researchers were alerted when three beaked whales were found stranded on the north and west coast of Ireland. These creatures feed on squid in deep waters and little is known about them. They are rare, and it is highly unusual for three to be stranded within a few days and weeks of each other as happened here

An adult female was stranded at Five Fingers Strand in Donegal and two days later a whale calf was found washed ashore about 2km away. Then two weeks later, a second adult female beaked whale was found stranded at Ballyconneely in Co Galway. The immediate questions were why?

Post mortem results found that the two adult females had macro-plastics in their stomachs, while micro-plastics were identified throughout the digestive tract of the single whale that was examined for micro-plastics.

Simon Berrow told me in an email that it was “very disturbing” that micro-plastics were found throughout the digestive tract of the one beaked whale which was examined for micro-plastics, as these whales are offshore, deep-diving species which are very rarely even sighted by humans.

There can be many reasons why a marine creature gets stranded, or washed up on a beach. For example, there has been an increase in the number of dead dolphins washing up on the west coast of Ireland since the start of 2016, with 28 animals stranded, the second highest number every recorded for the first two months of the year.

Most of the strandings, scientists say, were in Mayo, Sligo and Donegal and the evidence showed that the dolphins died when they were caught up in the large fishing nets of foreign registered super-trawlers fishing in Irish waters.

Dolphins and other cetaceans (whales and porpoises) are under pressure in Irish waters from the nest of super-trawlers, as well as depletion of their natural prey –

fish – due to

over-fishing by the same trawlers. Add to that, the issue of micro-plastics and it’s no surprise to note that

dolphin numbers are declining.

In Ireland we are producing in the region of 210,000 tonnes of plastic per year. Yet, we only recycle 36 per cent this plastic waste. That means that more than 100,000 tonnes of plastic here each year ends up buried in landfill sites, where experts say it could take 1,000 years to breakdown, or it finds it way to the sea.

Scientists in Ireland, and elsewhere, have grown concerned about a ‘steady stream’ of plastics entering our oceans and how that is affecting marine life. The evidence now emerging suggests that plastics are disrupting the balance of marine life to such an extent that it presents a real threat to all life on Earth.

About 45% of plastic waste is sent for burning, or waste-to-energy, as some would call it, while 15% or 30,000 tons is sent to landfill each year. The new Dublin ‘Waste-to-Energy’ plant due to open at Poolbeg in 2017, operated by Covanta, may help if it takes plastic waste that currently ends up put into domestic black bins – about 20% of all plastic waste.

Currently municipal solid waste, including plastic waste is sent for burning to European incinerators. Dealing with the plastic here, is in line with the proximity principle – that waste be dealt with as close to source as possible. It will also create jobs.

The amount of plastic waste is growing year on year by about 4% so this is not a problem that will be going away. The dumping of plastic waste is a big problem, according to a spokesperson for Repak (Ireland’s only industry-funded packaging recycling firm) with 80% of marine litter being plastic.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://irishtechnews.ie/uls-irish-composites-centre-wins-funding-to-tackle-scourge-of-plastic-waste/

http://coastmonkey.ie/westport-first-town-plastic-straw-free/

https://sciencespinning.com/2016/03/08/is-plastic-poisoning-our-oceans/

http://www.poferries.com/

https://www.irishferries.com/

ABS

- BIOMAGNIFICATION

- BP DEEPWATER - CANCER

- CARRIER BAGS

- CLOTHING - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING

NETS

FUKUSHIMA - MARINE LITTER

- MICROBEADS

- MICRO

PLASTICS - NYLON - OCEAN GYRES

- OCEAN WASTE -

PACKAGING - PCBS

PET - PLASTIC

- PLASTICS

- POLYCARBONATE

- POLYSTYRENE

- POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS -

PVC - SHOES

SINGLE USE

- STRAWS - WATER

AEGEAN

- ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- AMBRACIAN

GULF

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC

- BALTIC

- BAY

BENGAL - BAY

BISCAY - BERING

- BLACK

- CARIBBEAN

- CASPIAN

- CORAL

- EAST

CHINA SEA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC

- GUANABARA

- GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN

-

IRC - IONIAN - IRISH

- MEDITERRANEAN

- NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN

GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON

- PLASTIC

OCEANS - RED

- SARGASSO

- SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN - TYRRHENIAN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

- WOC

- WWF

GANGES

- NILE

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2025. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital. The names Amphimax™

RiverVax™

and SeaVax™

are trademarks.

|