|

PLASTIC

PLANET

ABOUT -

CONTACTS - FOUNDATION -

HOME - A-Z INDEX

From the

land to the sea our Earth is becoming a Plastic Planet. Most of the plastic waste in the

United

Kingdom doesn't actually end up in our oceans, but a lot is disposed of in our environment,

being burned or buried in landfill sites. Around 79% of the plastic waste ever created is still in our environment. We are leaving a legacy of plastic waste on our planet that will take

nearly 50 years

for our children to put right according to one published estimate.

Plastic in the oceans – marine litter or marine debris – is a threat to the ocean that has gained some attention in recent years, from media, NGOs, business entrepreneurs as well as policy makers. It is increasingly recognised that the damage to the ocean ecosystems also creates risks to social and economic systems (Oosterhuis et alii 2014, Watkins et alii 2017, Brouwer et alii 2017). There is an urgent need for a wide range of policies to keep plastic and its value in the economy and out of the ocean and the responses so far are far from what will be required. The new political focus on the circular economy offers a window of opportunity to encourage upstream measures (eg product design and multiuse products), consumer measures (awareness and pricing to inform purchasing and waste disposal habits) and downstream measures (eg collection and recycling) (ten Brink et alii 2016).

More and more people are recycling but we still only recycle 58% of our plastic bottles – that's a 42% gap.

Plastic bottles are accepted for recycling by 99% of local councils in the

UK. We only recycle 32% of the plastic pots, tubs and trays we buy and these are widely collected for recycling.

It all adds up to plastic being needlessly burned or dumped in landfill every year. Some of that plastic ends up polluting our environment.

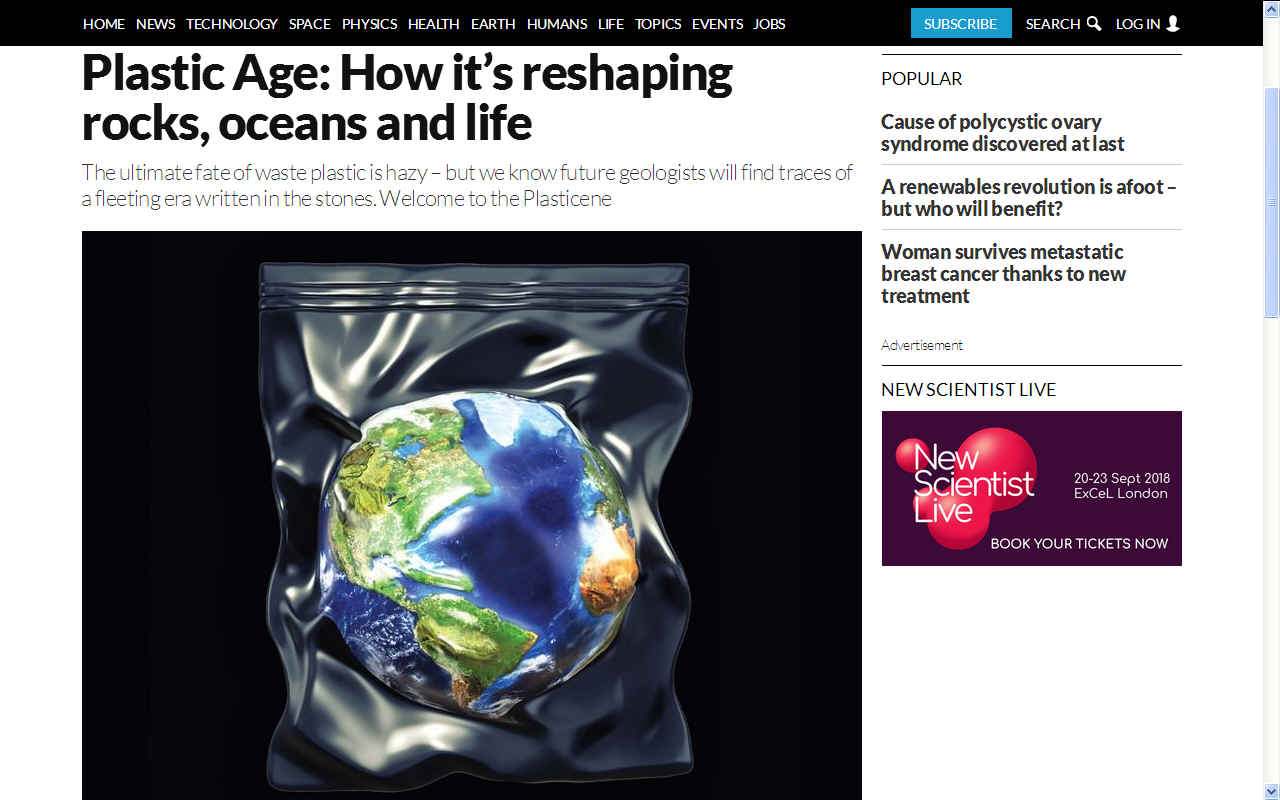

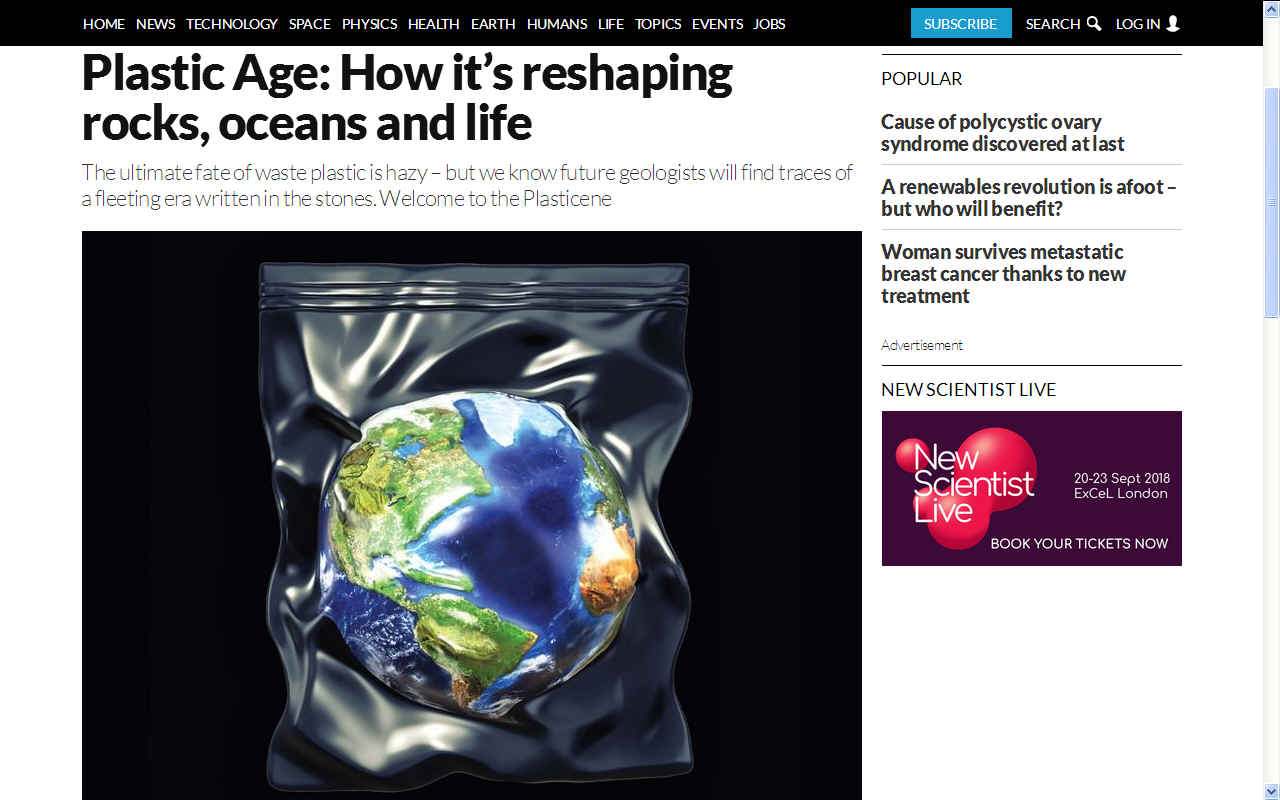

One million years from now, geologists exploring our planet’s

concrete-coated crust will uncover strange signs of civilisations past. “Look at this,” one will exclaim, cracking open a rock to reveal a thin black disc covered in tiny ridges. “It’s a fossil from the Plasticene age.”

Not quite as good as Planet

of the Apes, but still the demise of a civilisation.

Our addiction to plastics, combined with a reticence to recycle, means the stuff is already leaving its mark on our planet’s geology. Of the 300 million tonnes of plastics produced annually, about a third is chucked away soon after use. Much is buried in landfill where it will probably remain, but a huge amount ends up in the oceans. “All the plastics that have ever been made are already enough to wrap the whole world in plastic film,” palaeobiologist Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester, UK, recently told a conference in

Berlin,

Germany. It sounds enough to asphyxiate the planet.

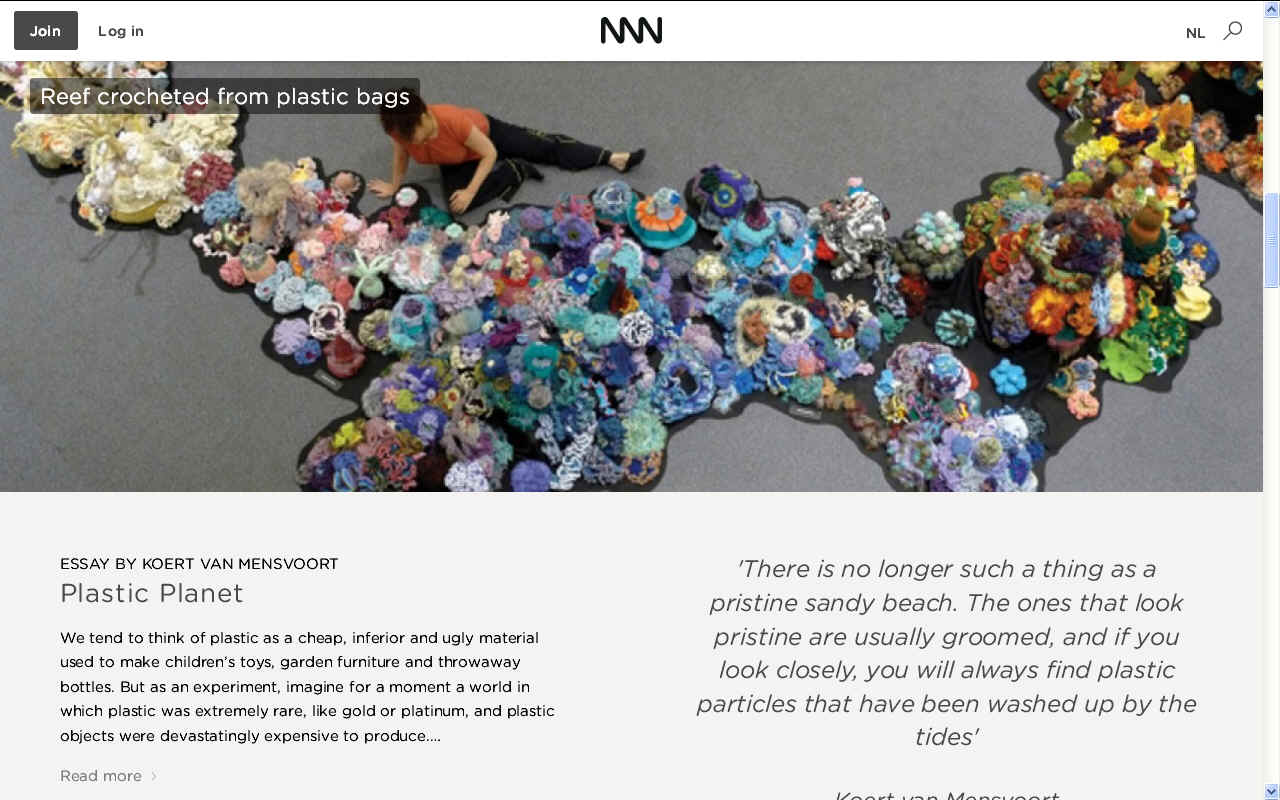

The United States throws out 25 billion

plastic water bottles each year; a ‘patch’ of plastic garbage twice the size of Texas now swirls in the center of the Pacific Ocean. From its invention in 1907, plastic and plastic-derived chemicals have worked their way into the rungs of every food chain on Earth. Plastic might be the newest nutrient in the planet’s ecosystems, but so far, nature has yet to find a use for it. The only sensible way to think of plastic is as a raw Next Nature material, waiting for its balancing counterpart to evolve. We only have time: the average plastic bag will linger for your great grandchildren to clean up 1,000 years from now.

CHARLES MOORE

In 1997, a Californian sailor named

Charles Moore was heading home from a sailing race in

Hawaii and decided to take a shortcut across the edge of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (a region often avoided by seafarers). It was here that he came upon an enormous stretch of floating debris. Throughout the week it took him to traverse the area, there was always some piece of plastic bobbing by: a bottle cap, a toothbrush, a cup, a bag, and a torrent of unidentifiable pieces of plastic bits. Moore sensed there was something terribly wrong here. Two years later, he returned with a fine-mesh net, and discovered, floating beneath the surface, a multicoloured multitude of small plastic flecks and particles, like snowflakes or

fish food. Moore had identified what is now called

“the Great Pacific Garbage

Patch,” an area in the central North Pacific Ocean that is larger than the territory of

France or Texas, which contains exceptionally high concentrations of marine trash.

The fact that plastic hardly breaks down is well-known, but rarely talked about. Plastic does not biodegrade, as microbes haven’t evolved to feed on it. It can photo-degrade, however, meaning that sunlight causes its polymer chains to break down into smaller and smaller pieces, a process catalyzed by friction, as when pieces are blown across a beach or rolled by waves. The same process is in play when pieces of rock are rounded by

ocean waves. It is this type of frictional erosion that accounts for the majority of unidentifiable flecks and fragments making up the massive plastic soup at the heart of the Pacific.

Captain Moore is quoted as saying: “As I gazed from the deck at the surface of what ought to have been a pristine ocean,” Moore later wrote in an essay for Natural History, “I was confronted, as far as the eye could see, with the sight of plastic. It seemed unbelievable, but I never found a clear spot. In the week it took to cross the subtropical high, no matter what time of day I looked, plastic debris was floating everywhere: bottles, bottle caps, wrappers, fragments.” An oceanographic colleague of Moore’s dubbed this floating junk yard “the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” and despite Moore’s efforts to suggest different metaphors — “a swirling sewer,” “a superhighway of trash” connecting two “trash cemeteries” — “Garbage Patch” appears to have stuck.

Captain Moore’s research revealed six times more plastic in the area than plankton. It was also discovered that 80 percent of the debris had initially been discarded on land – a finding later confirmed by the

United Nations Environmental Program. Wind blows the plastic through streets and from landfills. It makes its way into rivers, streams and storm drains, then rides the tides and currents out to sea, finally ending up in an ocean gyre. And the trash-vortex Moore discovered isn’t the only one – the planet has six additional major tropical oceanic gyres, all of them swirling with debris.

Moore is the founder of the Algalita Marine Research and Education in Long Beach, California, and currently works there.

In 2008 the Foundation organized the JUNK Raft project, to "creatively raise awareness about plastic debris and pollution in the ocean", and specifically the Great Pacific Garbage Patch trapped in the North Pacific Gyre, by sailing 2,600 miles across the Pacific Ocean on a 30-foot-long (9.1 m) raft made from an old Cessna 310 aircraft fuselage and six pontoons filled with 15,000 old plastic bottles. Crewed by Dr. Marcus Eriksen of the Foundation, and film-maker Joel Paschal, the raft set off from Long Beach, California on 1 June 2008, arriving in Honolulu, Hawaii on 28 August 2008. On the way, they gave valuable water supplies to Ocean rower Roz Savage, also on an environmental awareness voyage.

Plastic now forms part of our planet’s food chain. The problem is that nothing in the food chain can digest it. Plastic ends up in the bellies of all kinds of sea creatures – from fish, to turtles, to albatrosses. According to the

United Nations Environment Program, plastic is killing a million seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals and turtles every year. And this is in addition to the deaths by entanglement caused by six-pack rings and discarded synthetic fishing lines and nets. They also clog animals’ throats and digestive tracts, leading to fatal constipation. One wonders what

Charles

Darwin would have thought of the albatross babies fed bellyfuls of plastic by their albatross parents, who soar out over the vast, polluted ocean collecting what looks to them like food for their young. We know by now that every second nature stresses a first nature, which, in effect, deteriorates; the victorious second nature then becomes the first. But are we ready for a plastic planet?

NEWS

MOBILE AUGUST 2017 - The ‘Age of Plastic’ is coming and if the pollution levels continue to rise, Earth will soon turn into a plastic planet.

Humans have created more than 8 billion metric tons of plastic since the large-scale production of synthetic materials began in the early 1950s and it’s enough to cover the entire country of Argentina and most of the material now resides in landfills or in the natural environment.

Such are the findings of a new study led by UC Santa Barbara industrial ecologist Roland Geyer. The research provides the first global analysis of the production, use and fate of all plastics ever made, including synthetic fibres.

“We cannot continue with business as usual unless we want a planet that is literally covered in plastic,” said lead author Geyer. “This paper delivers hard data not only for how much plastic we’ve made over the years but also its composition and the amount and kind of additives that plastic contains. I hope this information will be used by policymakers to improve end-of-life management strategies for plastics.”

Geyer and his team compiled production statistics for resins, fibres and additives from a variety of industry sources and synthesized them according to type and consuming sector.

They found that global production of plastic resins and fibres increased from 2 million metric tons in 1950 to more than 400 million metric tons in 2015, outgrowing most other man-made materials. Notable exceptions are steel and cement. While these materials are used primarily for construction, the largest market for plastics is packaging, which is used once and then discarded.

“Roughly half of all the steel we make goes into construction, so it will have decades of use; plastic is the opposite,” Geyer said. “Half of all plastics become waste after four or fewer years of use.”

And the pace of plastic production shows no signs of slowing. Of the total amount of plastic resins and fibers produced from 1950 to 2015, roughly half was produced in the last 13 years.

“What we are trying to do is to create the foundation for sustainable materials management,” Geyer added. “Put simply, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and so we think policy discussions will be more informed and fact-based now that we have these numbers.”

The researchers also found that by 2015, humans had produced 6.3 billon tons of plastic waste. Of that total, only 9 percent was recycled; 12 percent was incinerated and 79 percent accumulated in landfills or the natural environment. If current trends continue, Geyer noted, roughly 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste — weighing more than 36,000 Empire State Buildings — will be in landfills or the natural environment by 2050.

“Most plastics don’t biodegrade in any meaningful sense, so the plastic waste humans have generated could be with us for hundreds or even thousands of years,” said co-author Jenna Jambeck. “Our estimates underscore the need to think critically about the materials we use and our waste management practices.”

The investigators are quick to caution that they do not seek to eliminate plastic from the marketplace but rather advocate a more critical examination of plastic use.

“There are areas where plastics are indispensable, such as the medical industry,” said co-author Kara Lavender Law. “But I do think we need to take a careful look at our use of plastics and ask if it makes sense.”

The study appears in the journal Science Advances.

The swirling pile of trash in the

Pacific Ocean Gyre is growing at an exponential rate. A recent study has estimated that the mass of the garbage island is four to sixteen times bigger than previously thought, and is now three times the size of

France. Mon dieu!

From its invention in 1907, plastic and plastic-derived chemicals have worked their way into the rungs of every food chain on

Planet

Earth. Plastic might be the newest nutrient in the planet’s ecosystems, but so far, nature has yet to find a use for it.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5443811/Oceans-turned-toxic-plastic-soup.html

https://plasticoceans.org/

https://www.ted.com/speakers/charles_moore

http://newsmobile.in/articles/2017/08/05/lifestyle-choices-turning-earth-plastic-planet-2/

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22530060-200-plastic-age-how-its-reshaping-rocks-oceans-and-life/

https://www.nextnature.net/themes/plastic-planet/

https://www.recyclenow.com/plastic-planet

http://aplasticplanet.com/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/n3ct3v27

SINGLE

USE PLASTICS - This is

just a small sample of the plastic packaging that you will

find in retails stores all over the world. A good proportion

of this packaging - around 8 millions tons a year, will end up

in our oceans, in the gut of the fish

we eat, in the stomachs

of seabirds and in the intestines of whales and other marine

mammals. Copyright photograph © 22-7-17 Cleaner

Ocean Foundation Ltd, all rights

reserved.

FOAM

& BOTTLES - Expanded polystyrene is

used to package household electrical goods, while soft drinks and water is

sold in PET plastic bottles by the billions every year. The numbers are

staggering. It's no wonder then that some of this plastic will end up on our

plate in one form or another, potentially as a toxin carrier. Copyright

photograph © 22-7-17 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd, all rights reserved. Animals do not recognize polystyrene foam as an artificial material and may even mistake it for food. Polystyrene foam blows in the wind and floats on water, due to its low specific gravity. It can have serious effects on the health of birds or marine animals that swallow significant quantities.

A-Z

- ABS

- BIOMAGNIFICATION

- BP DEEPWATER - CANCER

- CARRIER BAGS

- CLOTHING - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING

NETS

FUKUSHIMA - HEAVY

METALS - MARINE LITTER

- MICROBEADS

- MICRO

PLASTICS - NYLON - OCEAN GYRES

- OCEAN WASTE

PACKAGING - PCBS

-

PET - PLASTIC

- PLASTICS

- POLYCARBONATE

- POLYSTYRENE

- POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS

PVC - SHOES

- SINGLE USE

- SOUP - STRAWS - WATER

This

website is provided on a free basis as a public information

service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774)

2018. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL

is a charity without share capital.

|